The Malayan tiger is said to be the national animal of Malaysia.

The tiger appears in various heraldry of Malaysian institutions such as the Royal Malaysia Police, Proton – which is Malaysia’s first national car company, its universal bank, Maybank and the Football Association of Malaysia, among others. Even Malaysia’s national football team, the pride of the country, has been given the nickname ‘Harimau Malaya’ (Malayan tigers). The animal symbolises bravery and strength to all Malaysians.

Sadly, in reality, Malayan tigers are facing threats that could see the end of their days.

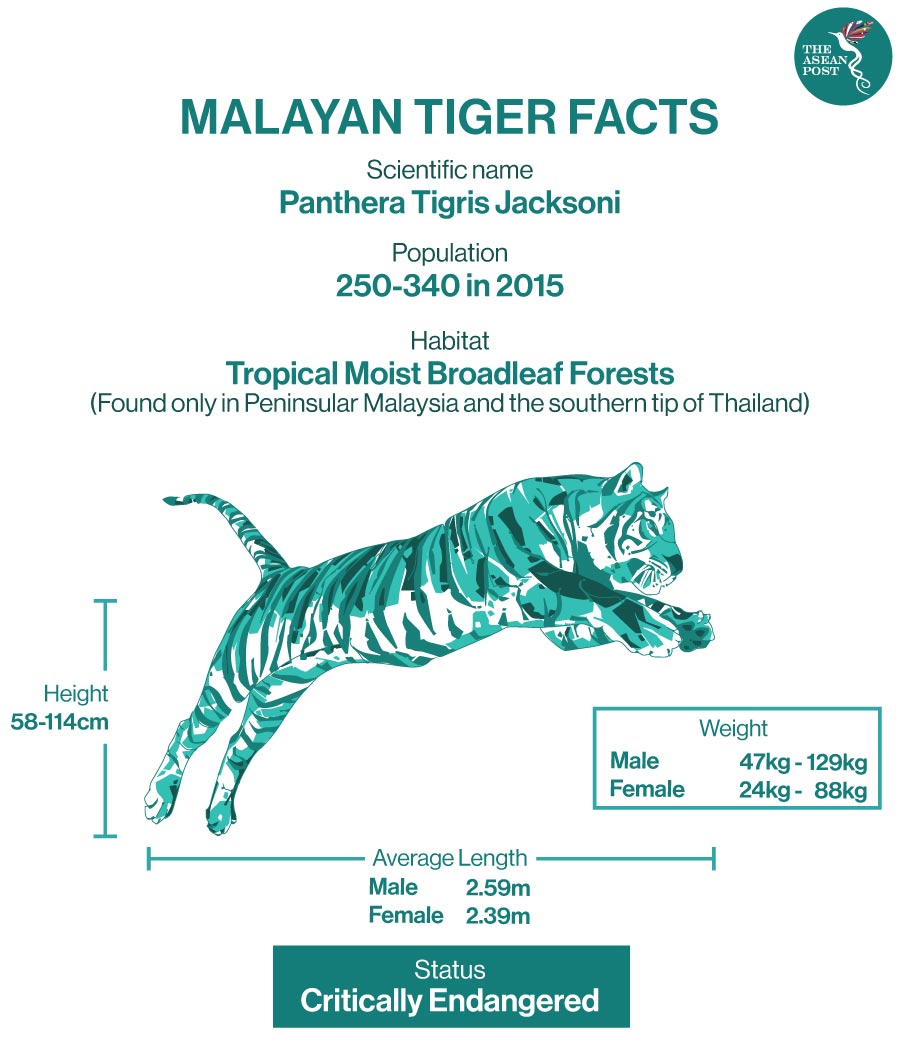

According to the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF), Malaysia was thought to have as many as 3,000 Malayan tigers back in the 1950s. Since then, numbers have deteriorated rapidly. In 2014, the number of the Malayan tigers was estimated to have declined to just 250 to 340.

The Malayan tiger is struggling to survive as human activities such as logging and development destroy its natural habitat, leaving it ever more vulnerable to poachers. The majestic animal is often slaughtered for its skin, bones, blood and sexual organs for use in traditional medicines. In other cases, they are sold to exotic meat restaurants and the illegal pet trade.

“It's our national emblem. It's supposed to represent courage. If we let this animal slide it will show we didn't have the courage to protect our own species. We owe it to our Malayan tigers to say that we can save this species in the wild,” said Mark Rayan Darmaraj, WWF-Malaysia’s Tiger Lead.

The species has also been classified as ‘Critically Endangered’ under the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List, with less than 200 left in the wild today.

Earlier this month at Malaysia’s 77th National Land Council Meeting, the concern was even raised by the country’s prime minister himself.

Premier Muhyiddin Yassin cited a national survey and said that there are currently around 130 to 140 Malayan tigers left in the ASEAN member state. He then urged state governments to take proactive measures in order to protect the wildlife and its habitat.

Canine Distemper

Back in March, a three-minute video of a tiger roaming and appearing to be “unafraid” and “harmless” went viral among villagers in Mersing in the southern state of Johor. For locals, the situation was similar to another incident which took place six months earlier, 300 kilometres away in Dungun, Terengganu, located on the west coast of the country.

In both cases, the tigers were found disoriented and underweight. Unfortunately, the two animals were also later found to have died from the canine distemper virus or CDV.

While Malaysia and other nations across the world are fighting the COVID-19 pandemic which has taken thousands of lives and ravaged livelihoods – another virus is also threatening the population of wild tigers.

CDV is a type of disease caused by a virus that commonly attacks domestic cats and dogs, but there have also been many cases involving tigers, wolves and foxes.

“It will cause the animal to be confused and go against its predatory instincts. This may be the reason why it does not harm humans and livestock that come into its path,” said Forestry Department director-general Abdul Kadir Abu Hashim. “A normal tiger will not refuse to (eat) man or livestock. If it doesn’t eat, it will attack due to its instincts or natural habits,” he added.

In addition, being afraid of humans is a behaviour symptomatic of the disease due to brain damage caused by the virus, stated a local media.

“The Malayan tiger is already declining due to poaching, habitat loss and fragmentation or degradation, as well as prey loss – and now CDV seems to be emerging as yet another threat,” Darmaraj told the media.

He also noted that if no immediate and drastic measures are taken to curb poaching, local extinction of the Malayan tiger would occur within three to four years.

In 2010, the World Bank organised the first-ever “Tiger Summit” and it was attended by 13 tiger nations including Malaysia. In unison, attendees set an ambitious goal to double wild tiger numbers worldwide by 2022, the next Chinese Lunar Year of the Tiger.

There is a large question mark over whether this goal can be achieved in Malaysia. Sadly, at the current rate of decline, it seems like we are witnessing the last days of the Malayan tiger.

Related articles: