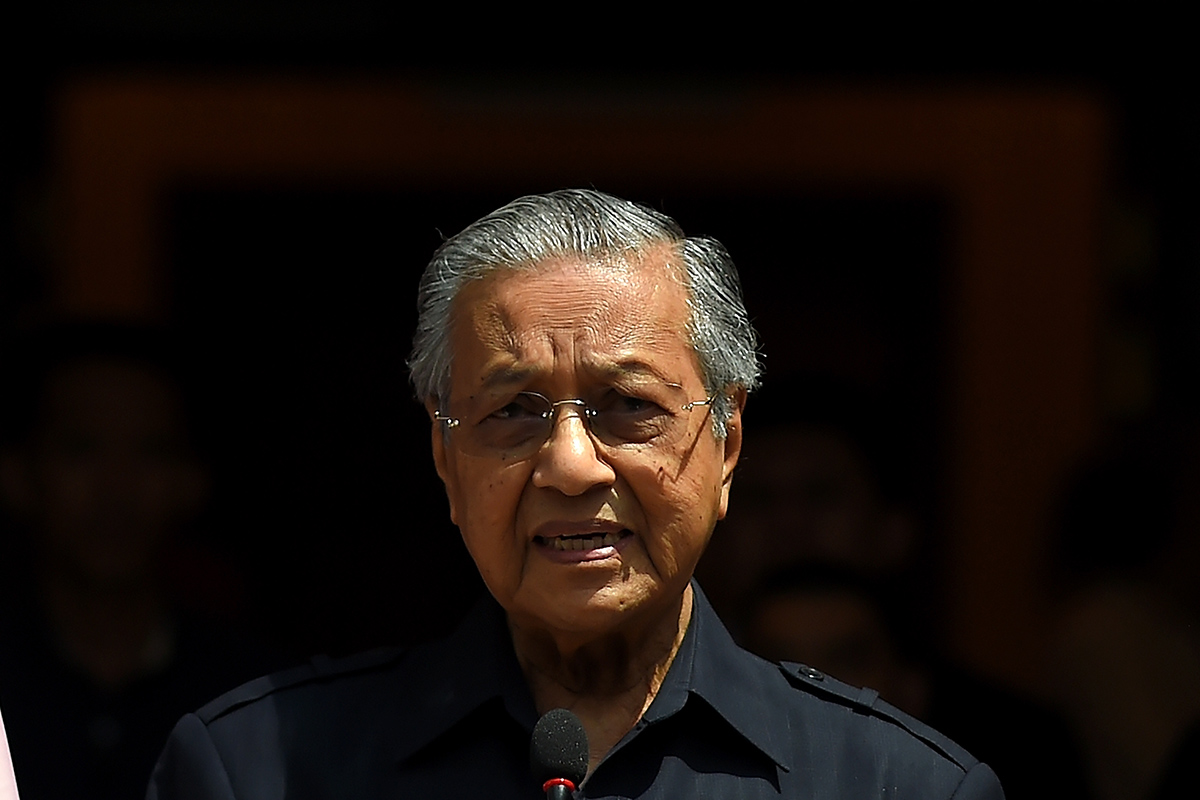

At 92, Malaysian Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad is now the world’s oldest elected leader. He’s also the first to return to power after a lapse of 15 years, at the helm of a different political party. His place in Asian history is assured.

There’s still room, however, to burnish his legacy. Mahathir doesn’t plan to remain in office long, only until his former deputy Anwar Ibrahim is pardoned of sodomy charges and wins a by-election for parliament. As a transitional prime minister, and given his own history, Mahathir has a unique opportunity to change the one and only thing holding Malaysia back: the Bumiputra, or “sons of the soil” policy.

Launched in 1971 as the New Economic Policy (NEP), this set of programmes sought to restructure Malaysian society and increase economic and educational opportunities for the ethnic Malay majority. Nobody, then and now, took issue with these aims. The Malay population had no real stake in the private sector at the time and, even now, they lag behind the Chinese and Indian communities in educational achievement and income.

Yet, as race-based policies were implemented, the goal somehow changed to promoting Malay supremacy in all aspects of Malaysian life. Quotas were imposed across a vast range of activities, including university admissions, recruitment into the civil service, scholarships and business loans and licenses. The government even created a university specifically for Malays, which has grown into Malaysia’s largest in terms of student population. Government programmes that couldn’t be justified on rational grounds could always be brought in under the umbrella of the Bumiputra policy.

Over the years, the NEP has created a class of Malay rent-seekers whose only role is to add 20 percent to 50 percent to the cost of projects. If the government has a public-works contract, for instance, only Bumiputra companies can tender for the job. Since there’s little or no competition, adding 20 percent to the price is simply a matter of changing a digit or two on the tender document. Once the contract is secured, the work is then sub-contracted to other businesses, minus the 20 percent. Everybody wins: the government helps the Malay community and the contractors, usually non-Malays, get jobs.

The losers are the Malaysian people and the Malaysian economy. That 20 percent cut goes into the pockets of politically connected cronies for doing nothing. The system has bred deep resentment among the non-Malay population, fuelling a brain drain as well as ethnic tensions that are obvious to any visitor to Malaysia.

Mahathir, who has long cast himself as a champion of the Malay community, and who expanded Bumiputra preferences during his first stint in power, has the credibility to explain to the Malay community why these policies no longer serve Malaysia. He doesn’t need to dismantle them immediately; that would be political suicide. Rather he needs to modify the NEP to bring it back to its original goals.

He can do this by declaring an end date for the policy, one that’s not too far into the future. Setting a deadline will force Bumiputra businesses out of their cocoon and pressure them to learn to operate efficiently. Mahathir should also lay down a gradual schedule to reduce the number of government contracts awarded solely to Bumiputra businesses; those that want the work in future will have to offer competitive tender prices.

There’s no reason to think Malay-owned companies can’t operate as efficiently as any others; they’ve simply not had to do so till now. Those who cannot cope will have to find another way to make money. While there’s no easy path to building a Bumiputra business class, allowing them to be rent-seekers isn’t the solution.

There’s a very small window of opportunity. Mahathir is the only Malaysian leader who has the historical stature, personal charisma and political capital to promote such changes. He has no more political races to run after this one and nothing to lose. He also has the backing of the newly triumphant opposition coalition, many of whose members have long chafed at the country’s Malay preferences. It’s unlikely that Anwar, who has argued for reforming affirmative-action policies, would undo Mahathir’s actions once in office.

If nothing is done, on the other hand, Malaysia will find it impossible to compete in a region undergoing rapid economic change. Countries like Vietnam are running twice as fast as Malaysia. Two decades from now, if nothing changes, the two most uncompetitive economies in Southeast Asia could well be Malaysia and Brunei. That would serve Malays no better than any other Malaysians. – Bloomberg.