Every day, Jakarta’s 13.5 million people face water-related risks. Some have too much water, while others just do not have enough. Some have water but it is not consumable because of dirt or salt. Some even face the threat of sea water entering their homes. As grave as the situation is, for Jakartans in this megacity, conditions are expected to worsen as a result of climate change. Unless adaptation measures are taken, Jakarta's situation will be particularly bleak, with parts of the city becoming unliveable.

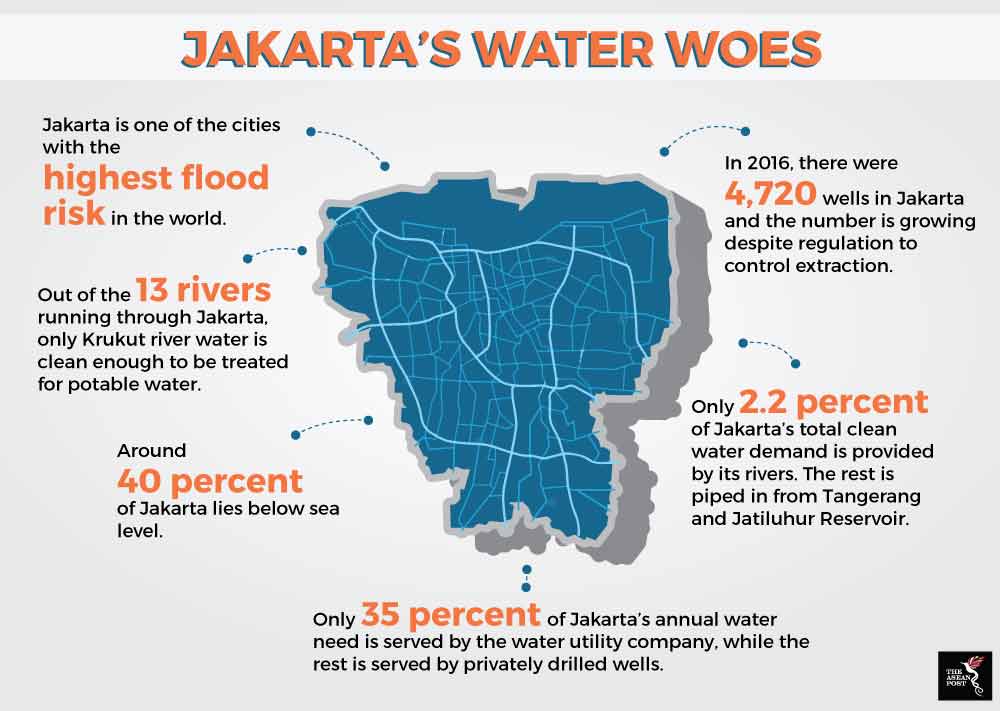

The struggle is real. Currently, around 40 percent of Jakarta lies below sea level and continuous land subsidence is making Indonesia’s capital the fastest sinking city in the world. The megacity is one of the cities with the highest flood risk in the world, frequently bearing the brunt of pluvial, fluvial and tidal flooding.

Only 35 percent of Jakarta’s annual water need of up to 1.27 billion litres is served by its water utility company, while the rest is mostly served by privately drilled wells. In 2016, there were as many as 4,720 wells in Jakarta and this number is always growing despite existing regulation to control groundwater extraction. The heavy reliance on groundwater is driven by the lack of clean surface water. Out of the 13 rivers running through the capital, only the water from Krukut river is clean enough to be treated for potable water, providing a mere 2.2 percent of the megacity’s total clean water demand.

Source: Various sources.

Solving existing issues

However, the biggest climate adaptation measures Jakarta needs to undertake are not specific to climate change. Climate risk and adaptation specialist, Dr Sarah Opitz-Stapleton, said Jakarta needs to end its dependency on groundwater and provide reliable water supply, as well as wastewater and waste management systems for its people. This is on top of restricting construction along coastal zones, rivers and remaining lakes.

“Climate change will not only create new risks for natural and human systems, but also amplify existing risks. Nearly 40 percent of Jakarta is already below today's sea levels because of all the groundwater extraction and excessive construction won't allow rainwater to infiltrate the ground and recharge aquifers. Monsoon rains have also been intensifying in Jakarta and surrounding areas. The city is effectively a bowl and experiences significant flooding. This situation will significantly worsen under climate change unless the needed adaptation measures are made,” stressed Sarah.

Read more: Jakarta has that sinking feeling

This is echoed by a 2050 projection of coastal flooding in Jakarta in a 2016 joint study by Tokyo Institute of Technology, The University of Tokyo and Waseda University which showed that while sea level rise (SLR) is a big factor in future coastal flooding in Jakarta, much of the inundation will be due to land subsidence. The projection estimated that coastal flooding deeper than one metre will potentially inundate 25.7 km2 and 110.5 km2 by 2025 and 2050, respectively, taking into consideration both SLR and land subsidence. If only SLR is considered, the estimated flooding will only affect 12.9 km2. The combination of these two factors could potentially induce extensive flooding by the middle of this century, reaching several kilometres inside the city. According to the study, the flooding is not linear, with the potential flooded area for the 2025-2050 time period estimated to be 3.4 times wider than during the 2000-2025 period.

Looking east for inspiration

Tokyo faced the same issues as Jakarta is experiencing now in the 1960s, when industries there carried out uncontrolled groundwater extraction, resulting in cumulative land sinking of up to 4.5 metres in certain areas. Within a decade of declined groundwater pumping, the rate of sinking slowed dramatically and was permanently halted in most areas. The water table rose even in the most affected areas and the rate of subsidence slowed to about one centimetre per year in five years.

Jakarta is the most vulnerable city in Southeast Asia to climate change impacts, which will result in increased flooding, SLR, increased storm frequency and intensity, and storm surges. It is also vulnerable to human-driven disasters such as severe water pollution and excessive groundwater extraction. These impacts have serious consequences on life and quality of lives, and on the economy. While difficult to solve, the situation is not entirely hopeless. Before it becomes irreversible, Jakartans and their relevant authorities need to take swift steps in the right direction.