With the mighty Mekong river running through the country, it is no surprise that Cambodia’s renewable energy sector is often associated with hydropower. This body of water flows southward from the Cambodia-Lao PDR border to the point below Kraceh city, where it turns west for about 50 kilometres and then turns southwest to Phnom Penh.

The Mekong is the longest river in Southeast Asia and is the 12th longest in the world. With approximately half of its length located in China, the Mekong flows for 4,620 kilometres and provides food and water for 60 million people. It is interesting to note that each year, 475 billion cubic metres of water is disgorged into the South China Sea from the ‘Mae Nam Khong’ which is the Thai and Laotian term for the aforementioned river.

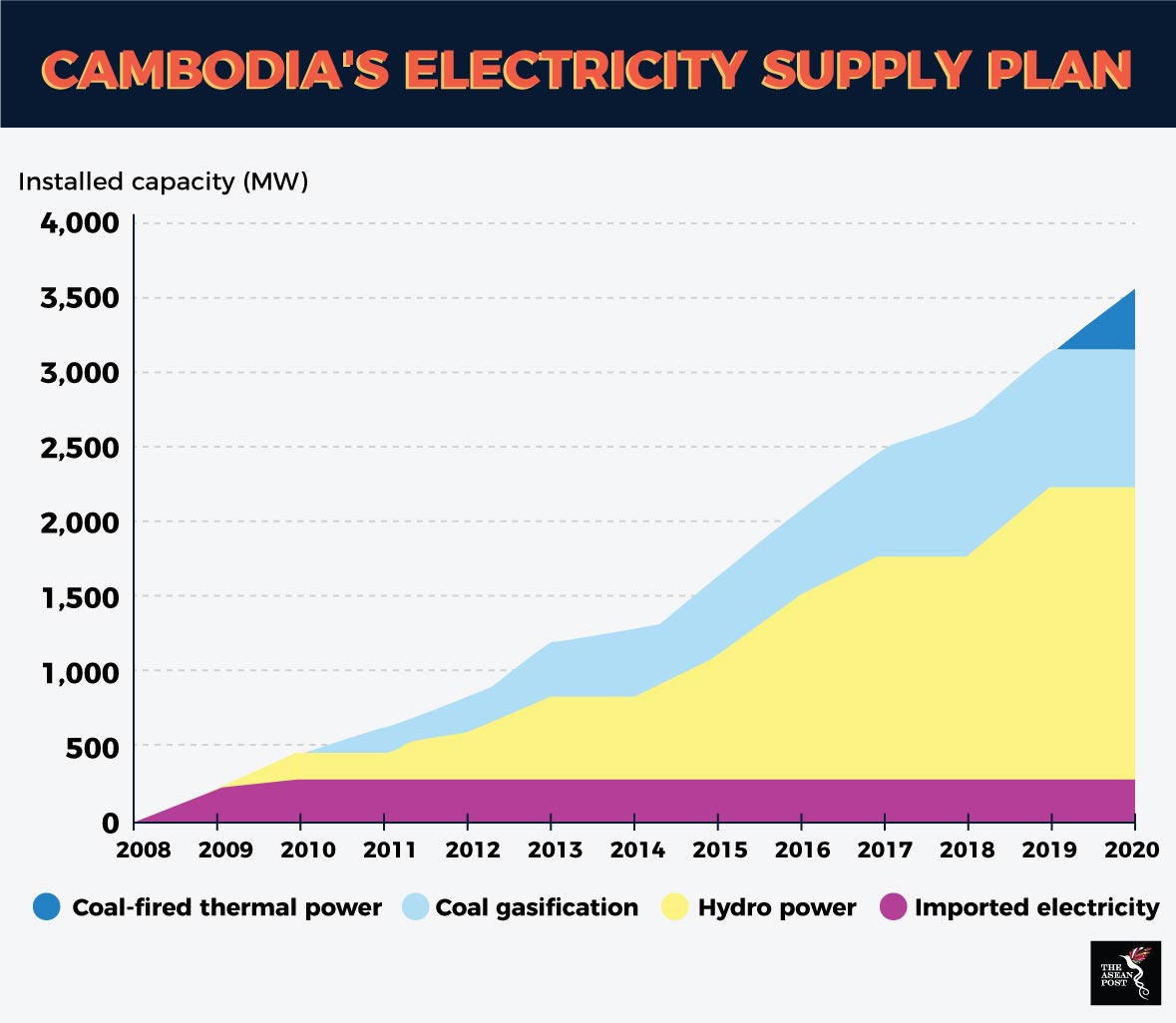

According to a report by the WWF, electricity consumption in Cambodia has been growing rapidly, averaging 20 percent growth per annum since 2010. This rate continues to accelerate as average incomes rise on the whole. As such, there is a growing impetus to meet the increased demands for electricity in the country, which was once under French rule. From this year on, Cambodia’s Ministry of Mines and Energy (MME) expects power imports to be substantially reduced as a proportion of electricity supply and to be able to meet demand almost entirely by means of domestic generation.

Based on research by Mekong Strategic Partners, a Phnom Penh based investment, advisory and risk management firm, Cambodia’s large-scale hydro and coal-filled generation plants currently provide power at between 8 to 11 cents/kWh. Solar installations above 1 MW (industrial facility scale) currently represents the most competitively priced alternative renewable energy technology.

Source: Asia Biomass Office

A report by the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) has highlighted Cambodia’s electrification target with 100 percent of villages in the Kingdom having access to basic electricity services by 2020. Its projection for 2030 is that at least 70 percent of all households in Cambodia have access to grid quality electricity. This is key to the Kingdom’s goal of bridging the development gap between its neighbours in the region.

Environmental and economic issues in the hydropower sector

Of utmost importance is that gains in electricity supply from hydropower initiatives be considered against local and broader environmental impacts. There are tangible and immediate risks for fisheries, farming, and food security in Cambodia because multiple upstream hydropower dams disrupt flood cycles, nutrient flows, and sediment transport. Added to this list is an interruption to migratory fish breeding.

A recent Mekong River Commission (MRC) study found that 11 hydropower dams under development in the Mekong River basin would reduce fish biomass by approximately 50 percent, if all were in operation. Farmers and fishermen will have to contend with the stressful situation of declining yields which will inevitably lead to decreased incomes. Consequently, Mekong delta food exports that are worth US$10 billion annually will be severely affected.

The MRC also explained that changes in the Mekong’s flow due to dam constructions will create negative effects on riparian ecosystems, sustainability, and food security associated with the fishing industry.

Through full hydropower development models, it is predicted that a reduction in lake and floodplain fisheries production across the Mekong basin will occur. Over the next couple of years, a staggering 70 percent decrease in the aforesaid production is bound to happen if the status quo is maintained. The economic implications are disastrous, with the projected annual GDP loss for the Kingdom being on the scale of US$3 billion to US$5 billion from 2020 to 2040.

The economic implications of Cambodia’s hydropower exploits have been acknowledged by the government. According to Nao Thuok, a Secretary of State at the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries, the Cambodian government is currently operating on projections of a 16 to 30 percent drop in fish biomass.

Moving forward, the Cambodian government must re-evaluate the ways in which hydropower is harnessed in the country. Admittedly it is difficult to balance both, environmental and economic considerations, a thorough engagement with not only energy companies but people on the ground (i.e. farmers, fishermen, etc.) ought to be carried out. Such a move would quell further concerns that might arise in relation to the livelihoods of these individuals who are more often than not, the breadwinners of their respective families.