The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) has stood strong for the past 50 years but in order to continue remaining relevant it must adapt to changes in the geopolitical environment.

In a commentary by Singapore based Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS), political scientist, Richard Javad Heydarian argued that ASEAN is progressively falling into a “middle institutional trap.”

“The type of decision-making arrangements that enabled it to reach its current stage of institutional maturity are insufficient to meet its newer challenges,” he explained.

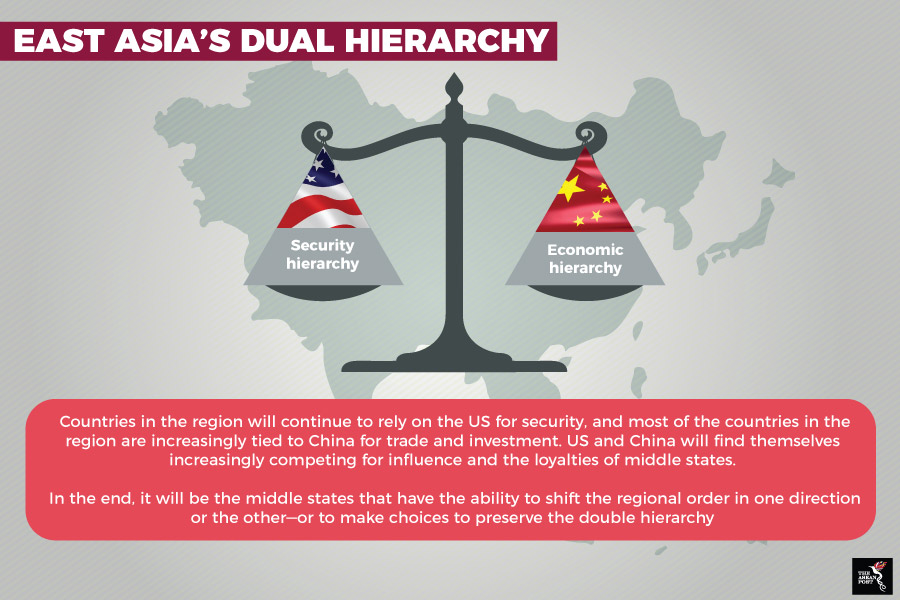

These challenges have arisen since the region fell within the radar of powers like China and the United States (US) – both of which would likely compete to expand their influence over ASEAN member countries. The myriad of issues facing the region calls into question the organisation’s resilience in ensuring it doesn’t fall apart due to the pressures of power politicking.

One way of doing so is to turn to minilateralism.

What is minilateralism?

Minilateralism stems from the practice of multilateralism by breaking down complex issues into smaller ones before addressing them.

In multilateral diplomacy, several states attempt to coordinate their interests in order to achieve a common goal. However, this is sometimes difficult to do. Hence, by tackling the specificities of complex issues in an ad hoc manner, competing state interests can be better addressed because there would be less factors to take into account.

Stewart Patrick, a Senior Fellow in Global Governance and Director of the International Institutions and Global Governance Program once referred to this issues-based collaboration in a Council of Foreign Relations (CFR) blog post as a “patchwork quilt of international cooperation.”

“Such ad hoc, disaggregated approaches to international cooperation bring certain advantages, including speed, flexibility, modularity, and possibilities for experimentation,” he further elaborated.

Source: Between the Eagle and the Dragon: America, China, and Middle State Strategies in East Asia by John Ikenberry

ASEAN minilateralism

ASEAN’s informal workings – undergirded by The ASEAN Way, gels well with the conduct of minilateral diplomacy. This long held principle has often been criticised for its stifling nature, but herein, lies an opportunity to rejuvenate The ASEAN Way and make it a more pragmatic notion.

The South China Sea dispute is a good example of an issue where achieving full consensus is near impossible. Between overlapping claims, claims of militarisation, land reclamation, island building, involvement of non-claimant ASEAN members, etc., such complexities invite a minilateralist solution.

Essentially, parties in the dispute can disaggregate the issue into well-defined areas and then tackle them within smaller forums. This will also make it easier for countries to engage in diplomatic trade-offs. On top of that, it will relinquish the role of non-claimants who may prove to be a detriment to the dispute resolution process. For example, Cambodia which many observers have come to consider as being within the Chinese orbit of influence; often times playing the spoiler role in the decision-making process.

In a commentary released by the ISEAS-Yusuf Ishak Institute, Tan See Seng, Professor of International Relations at at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS) mentioned that the practice of minilateralism is not without precedence in ASEAN.

“Diplomatically and functionally, minilateral maritime security collaboration on the South China Sea dispute makes good sense, given the shared security concerns among the littoral countries. Crucially, such cooperation is not intended to replace existing ASEAN based initiatives, but to complement them,” he added.

Moreover, ASEAN can also adopt an ASEAN Minus X approach – where some members come on board first as long as others agree to join later. According to Heydarian, such an effort is likely the best way forward “where likeminded and influential countries in the region coordinate their diplomatic and strategic calculations vis-a-vis South China Sea disputes.”

Minilateralism would mean that “ASEAN consensus” will have to take a back seat since only partial consensus would be needed at first. Such an effort doesn’t come without a fair bit of political zeal. But if the concept is embraced by ASEAN members, it could signal the normative evolution of The ASEAN Way where the bloc may be able to shake off its “sluggish” label.

More importantly, it would make the association a more effective one.