The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) is many things – a group of countries with a lucrative market waiting to be tapped, home to a large and young population and at the precipice of economic greatness as it seeks to capitalise on a rather bullish global economic outlook.

One thing ASEAN cannot seem to shake off though is its vulnerability to natural disasters. Collectively, the area encompassing the 10-member organisation is one of the most disaster-prone regions in the world.

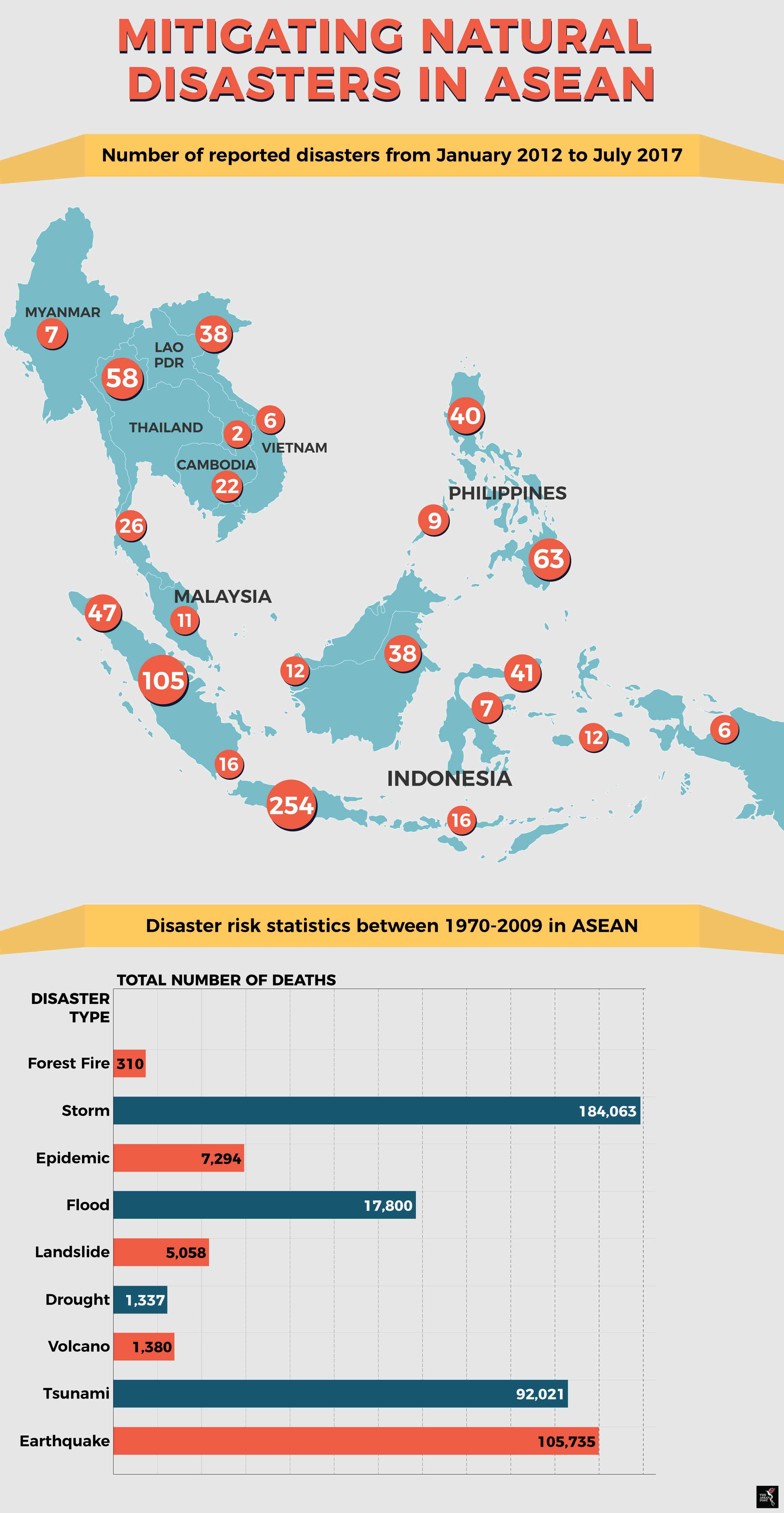

Between 2004 and 2014, the region contributed to more than half of global disaster fatalities – roughly 354,000 of the total 700,000 estimated deaths recorded. Natural disasters affected over 193 million individuals in the region, 191 million of whom were temporarily displaced. The total economic loss translated to an estimated US$91 billion.

Shockingly, despite newfound technologies in disaster mitigation, the disaster mortality rate in this region is on the rise. Deaths from natural disasters spiked more than sevenfold from eight deaths per 100,000 people between 1990 and 2003, to 61 deaths per 100,000 people between 2004 and 2014.

No one size fits all solution

Natural disasters come in all shapes and sizes. Some more predictable than others. Besides that, the geographic scope of its impact varies as well. While approaches to negate the impact of natural disasters may differ in accordance to the type of disaster faced, one thing should remain at the centre of all relief efforts – regionwide cooperation.

There is good reason for ASEAN member states to engage in joint disaster management exercises. Firstly, natural disasters can cause economic ripples throughout the region which therefore makes disaster mitigation a common interest among neighbouring countries.

For example, the 2004 Aceh earthquake triggered a series of devastating tsunamis which travelled as far west of the epicentre as the Somali coast. Indonesia paid the heaviest price as the earthquake not only caused the loss of over 200,000 lives in its wake but impacted the economy, resulting in billions of dollars in economic losses. Neighbouring countries were also impacted in the aftermath of the disaster.

Secondly, it is demonstrative of ASEAN’s cohesion in the face of criticism of its lacklustre response and reaction to manmade humanitarian crises. Large scale floods and cyclones like Cyclone Nargis in Myanmar or Typhoon Haiyan in the Philippines while being geographically limited, can still have a devasting impact in terms of lives lost and damage to livelihoods. Joint relief efforts coordinated by the ASEAN Coordinating Centre for Humanitarian Assistance on Disaster Management (AHA) were pivotal in providing relief goods and erecting temporary spaces for shelter as well as a disaster response base.

What can ASEAN do better?

Amid changes to global climate patterns, ASEAN has to be resilient and ready for what may come. In late 2017, the Union of Concerned Scientists, highlighted that tropical cyclones are becoming more rampant due to climate change.

To prepare for such challenges, leaders of ASEAN member states signed the ASEAN Declaration on One ASEAN One Response which aims to increase the speed, scale and solidarity of ASEAN’s disaster response. The declaration places the AHA Centre as the primary regional coordinating agency. The AHA Centre is tasked to operationalise the One ASEAN One Response and to develop necessary protocols, procedures and standards for disaster management and emergency response for ASEAN states.

Besides that, ASEAN needs to look into executing the ASEAN Agreement on Disaster Management and Emergency Response (AADMER) more effectively. The AADMER serves as a useful bedrock on which national-level policies can be harmonised and executed at a regional level. According to the ASEAN Vision 2025 on Disaster Management, the organisation needs to focus on three key areas to better apply the AADMER in the coming years.

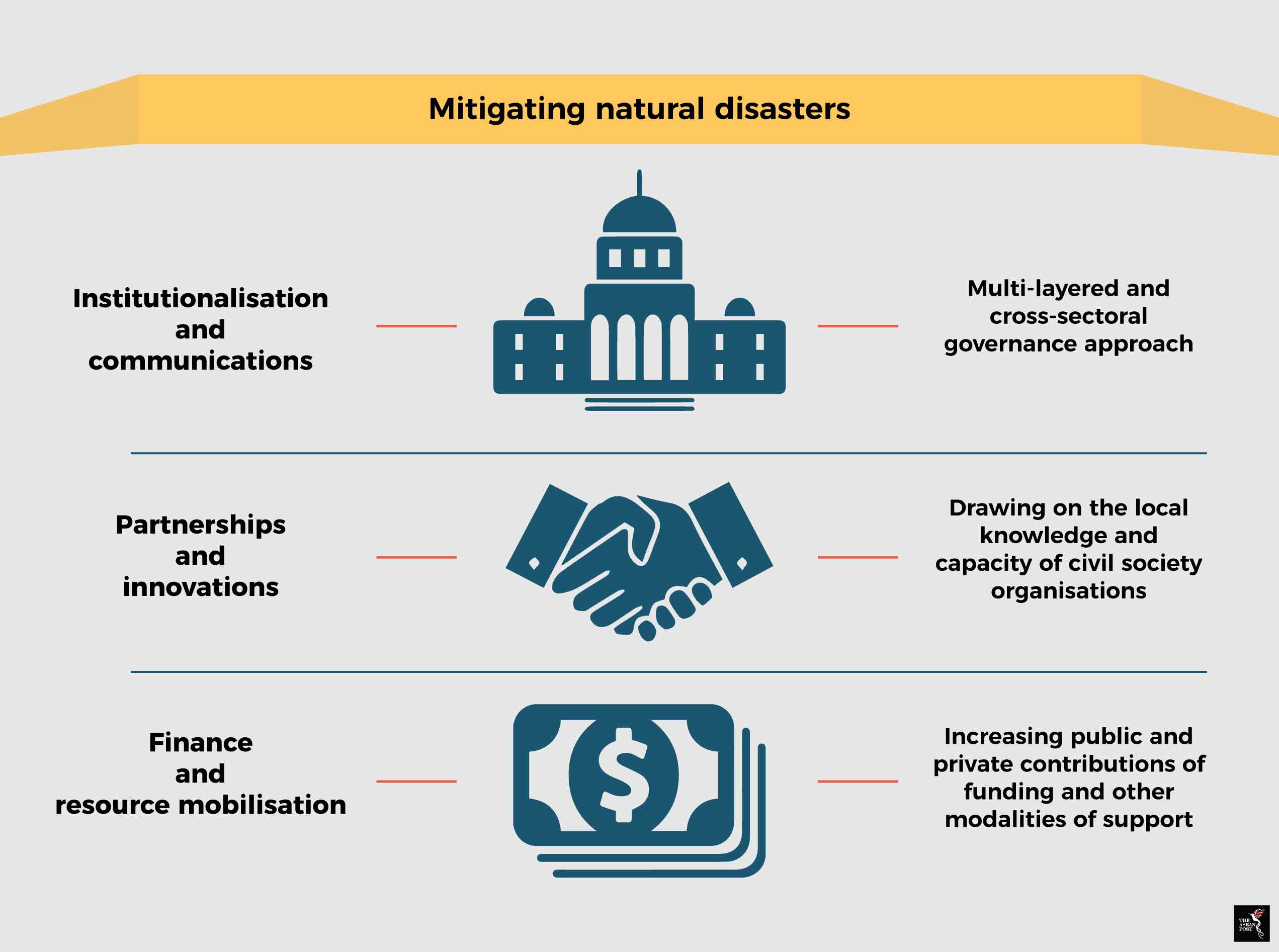

Firstly, the AADMER needs to be institutionalised at national and sub-national (city, provincial and community) levels. Such a multi-layered and cross-sectoral governance approach would make for a more holistic and effective disaster response.

Next, there must be adequate financial and resource mobilisation to undergird the implementation of the AADMER. Besides contributions from ASEAN member states, private companies – especially those involved in the insurance sector – have much to offer in the pursuit of a disaster-resilient region.

Lastly, there must be sufficient public and private partnerships. Herein, the AHA Centre can act as coordinator to ensure that the network of civil society organisations, firms and relevant authorities can leverage on the strengths of each other in handling disaster mitigation. On top of that, region-wide think tanks could also be included in the process in order to benefit from their strategic policy analysis which would better fine tune disaster management efforts.