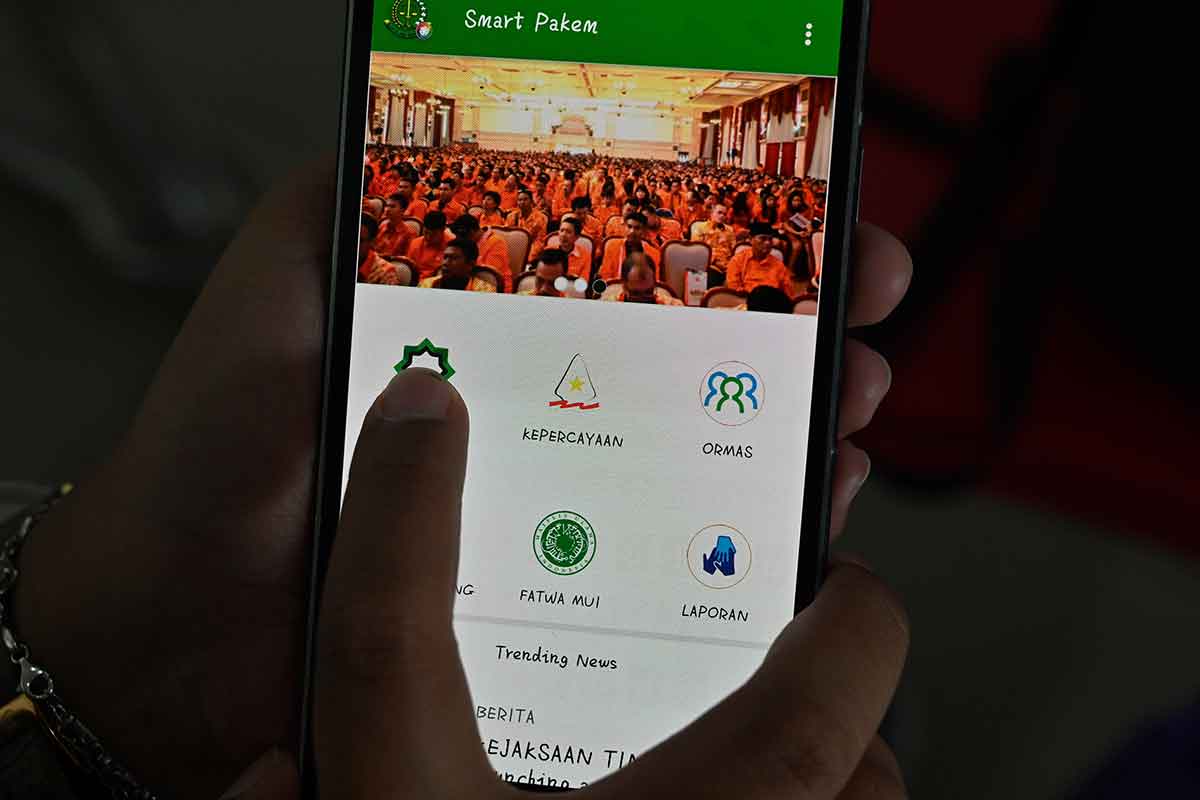

Indonesia’s National Commission on Human Rights recently voiced concerns regarding the launch of a mobile application by the Jakarta Prosecutor’s Office, which allows members of the public to report religious beliefs they consider “misguided”. The app, called “Smart Pakem”, features a list of groups including Ahmadiyyah as well as Gafatar, which the country’s highest Islamic council considers a deviant sect.

The free app became available for download on Google Inc’s Google Play store earlier this week.

The National Commission on Human Rights’ concerns stem from an allegedly rising intolerance in the country as well as the use of the country’s blasphemy laws against minorities. Islamic sects such as the Ahmadiyyah have also been targeted.

A commissioner from the National Commission on Human Rights, Amiruddin Al-Rahab, said that the app could have a “dangerous” consequence by causing social disintegration.

“When neighbours are reporting on each other, that would be problematic,” he said.

Conservatism on the rise

A survey commissioned by the ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute last year found that 63 percent of Indonesians support punishing blasphemy against Islam. Of these, 58 percent also felt it important to vote a Muslim leader into office. Meanwhile, 82 percent considered the wearing of the hijab or Islamic headscarf an important outward sign of Islamic religiosity for women.

The survey was conducted across all 34 Indonesian provinces between 20 and 30 May, 2017 and involved a sample size of 1,620 respondents. It indicates that conservatism in Indonesia is certainly on the rise.

One expert, however, believes that this rise in conservatism may be a global phenomenon and not just peculiar to Indonesia.

According to Jeffrey Kenney, professor of religious studies at DePauw University, the rise in conservatism may also be political in nature and could be linked to the rise in political conservatism as well.

Source: ISEAS - Yusof Ishak Institute

Source: ISEAS - Yusof Ishak Institute

Political benefit

Kenney says that in authoritarian settings, governments incline toward conservatism to prove their religious legitimacy to the masses, which tend to be more conservative than liberal.

“Such governments are more often than not secular, but religious conservatism provides a good public cover,” he told The ASEAN Post.

“Around the world, the rise of nationalism, in countries like Russia and Poland, even the United States (US), have been accompanied by genuflects toward traditional religious pieties and institutions, again, even when the nationalist leaders are anything but religious.”

Based on Kenney’s assertions, what could be happening in Indonesia is that President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo appears to be trying to appease conservatives by pandering to their sensitivities.

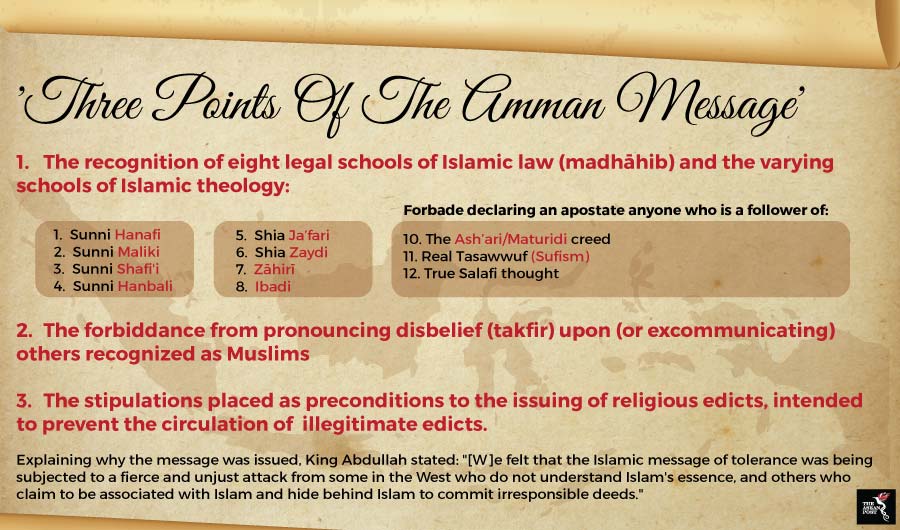

The Amman Message

The Amman Message is a statement calling for tolerance and unity in the Muslim world that was issued on 9 November 2004 by King Abdullah II bin Al-Hussein of Jordan. Subsequently, a three-point ruling was issued by 200 Islamic scholars from over 50 countries, focusing on issues of defining who is a Muslim, excommunication from Islam (takfir), and principles related to delivering religious edicts.

Because the Amman Message has been endorsed by such a large and reputable body of scholars, there is Islamic legitimacy to the statement.

When looking at the “Smart Pakem” app with the Amman Message in mind, there are a number of possible scenarios that could play out as Indonesia’s Muslims begin to utilise the app. It would be wise for both, the Indonesian government and its Islamic leaders to bear this in mind.

The first scenario concerns the Ahmadiyyah and their position in the Amman Message. Zia H Shah, chair of Religion and Science for the Muslim Sunrise, the oldest Muslim publication in North America, questioned whether the Ahmadiyyah should be considered legitimate Muslims following the definition in the Amman Message:

“Whosoever is an adherent to one of the four Sunni schools (mathahib) of Islamic jurisprudence (Hanafi, Maliki, Shafi‘i and Hanbali), the two Shia schools of Islamic jurisprudence (Ja‘fari and Zaydi), the Ibadi school of Islamic jurisprudence and the Thahiri school of Islamic jurisprudence, is a Muslim. Declaring that person an apostate is impossible and impermissible.”

Shah, who is also a physician, argues that since the Ahmadiyya Community follows the Hanafi-Islamic jurisprudence, they should be considered Muslims.

Source: Various sources

Source: Various sources

Another scenario concerns the Shia. The 2010 report to the United States (US) Congress by the US Commission on International Religious Freedom noted attacks against the Shia communities in Sunni-majority Indonesia. In one incident in Madura, local villagers surrounded Shia houses and demanded they desist religious activities, but the crowd was dispersed by local leaders and clergy.

While Smart Pakem poses problems for the Ahmadiyyah, it may in fact prove useful to Indonesian Islamic authorities in ensuring that Shia Muslims are treated fairly as Muslims. On the other hand, Amiruddin is concerned that since all the app’s features were not fully running, it could cause confusion among riled-up conservative Muslims.

“Don’t leave the people in confusion, if people are confused, they will take matters into their own hands,” he said.

Regardless of the road Indonesia’s authorities end up taking, it is clear that there is still a lot of thought that needs to be put into the app before it is allowed to go mainstream.

Related articles:

Indonesian elections: Conservatism versus moderation

Putting a lid on religious intolerance