While it has all the hallmarks of transnational organised crime, the illegal wildlife trade continues to be viewed as being outside ‘mainstream crime’.

Frequently linked to other forms of serious crime such as fraud, corruption and money laundering, the illegal wildlife trade generates an estimated US$20 billion annually and is the fourth most profitable criminal trafficking enterprise behind drugs, arms and human trafficking according to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC).

However, the cutting edge investigative techniques often employed in tackling other criminal investigations such as fraud and human trafficking are rarely employed when it comes to the illegal wildlife trade.

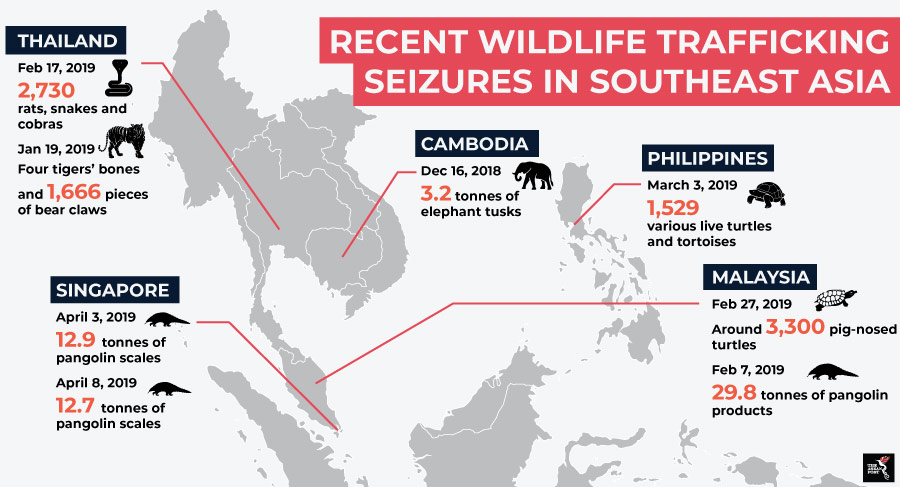

Driven by its demand as a source of alternative medicine or as status symbols, the illegal wildlife trade is rampant in ASEAN and there needs to be greater recognition of it as a financial crime so that appropriate financial investigations and law enforcement can be carried out and action taken to prosecute traffickers for money laundering.

‘A substantial money laundering threat’

“Proceeds from illegal wildlife trafficking qualify as proceeds of crime, and moving illicit money into the financial system makes them money launderers,” Tim Phillipps, APAC Financial Crime Network Leader and Southeast Asia Leader for Forensic and Analytics at Deloitte, told The ASEAN Post.

“Payments within the supply chain are in substantial amounts and will require the movement of these illicit funds in and out of legitimate financial facilities, making wildlife crime a substantial money laundering threat,” he stressed.

Phillipps explained that to legitimise illicit money, illegal wildlife traffickers will leverage the formal financial systems through banks, money exchanges and cryptocurrency markets, and the cross-border nature of wildlife trafficking means that organised criminal syndicates are able to park their money at many transit locations that have trading companies, transportation or travel businesses.

One of the region’s most notorious wildlife smugglers, Kampanart Chaiyamart used his extensive network to traffic live pangolins, orangutans, elephant ivory and other rare animals from Southern Thailand to China. Caught in December 2017, the Thai Anti-Money Laundering Office (AMLO) found that he had laundered 1.18 billion baht (US$35 million in 2014) between 2011 and 2014 using as many as 28 separate accounts and connections in Thailand, Vietnam, Lao and Malaysia to move money through numerous cash transactions.

In Malaysia, the record RM1.56 million (US$372,000) fine handed down to two Vietnamese nationals convicted of illegal possession of 141 threatened and protected animal parts on 15 May marked the first time in the country’s history that a fine of more than RM1 million (US$239,000) had been issued for a wildlife crime. While praising the record fine as a deterrent for future smugglers and poachers, wildlife trade monitoring network TRAFFIC suggested that those who are able to pay such fines should then be subject to further money laundering investigations.

Challenges

While a number of ASEAN countries have identified wildlife crime as a serious crime under their national anti-money laundering legislation, TRAFFIC says it is a problem that needs much closer scrutiny by government and financial institutions.

“Recognising it as a serious crime is a first step, but investigations must be pursued to demonstrate that we are walking the talk,” Elizabeth John, Senior Communications Officer at TRAFFIC Southeast Asia told The ASEAN Post.

While some Southeast Asian countries are doing well to investigate and prosecute wildlife crimes – and have begun looking into the illicit financial flows stemming from wildlife crime – others struggle to even bring a wildlife crime case to court and see it through to a successful conviction.

John said reasons for this includes weak laws riddled with loopholes, low fines and penalties, poor investigation capacities, lack of dedicated prosecutors to manage cases and judicial systems that do not consider wildlife crime as a serious crime despite it being classified as such.

To combat the illegal wildlife trade, Phillipps believes there must be a faster and better coordinated global pursuit by regulators, law enforcement and financial institutions; all tackling the issue with an anti-money laundering approach.

While it is difficult to track the changing hands of wildlife crime, a person’s digital footprint can be used to trace and disrupt money flows. Analysing suspicious monetary patterns and monitoring transactions such as trade finance and shipping activities will also help raise alarm bells.

As Phillipps said; “At the end of the day, it’s all about following the money.”

Related articles:

Wife of ex-Malaysian PM arrested

ASEAN’s human trafficking woes

Rhino horn seizure in Thailand leads to major trafficking syndicate