Education plays a vital role in the economic development of a country as it increases the capacity and ability of people to be more productive economically. Every child – even those living in poverty, in war-torn areas or those living with disabilities – has a right to education.

As stated by Save the Children, a leading humanitarian organisation for children, education is the route out of poverty for many people. It gives them a chance to gain the knowledge and skills needed to improve their lives.

Southeast Asian nations have made numerous efforts and plans in order to improve their education systems and standards. Prayut Chan-o-cha, Thailand’s premier, has promised first-rate education as a way for the kingdom to become a developed country by 2036.

Whereas fellow ASEAN member state Indonesia vows to build a “world-class” education system by 2025. The governments of Cambodia and Lao are also aware that education standards must be prioritised and improved if their economies are to shift from low-cost, low-skilled manufacturing, writes David Hutt in his article titled, “Confronting Southeast Asia’s Big Education Challenge.”

According to the 2019 ASEAN Key Figures report, all 10 ASEAN member states have made significant progress in ensuring primary education enrolment, with an enrolment rate of more than 90 percent in 2017.

As for the enrolment rate for secondary education, almost all Southeast Asian countries experienced an increase in the last decade. A significant increase of more than 30 percent was recorded in Cambodia, Indonesia, Malaysia and the Philippines. Nevertheless, the report notes that there is still room for improvement as the net enrolment rate in secondary education is still below 80 percent in some ASEAN member states.

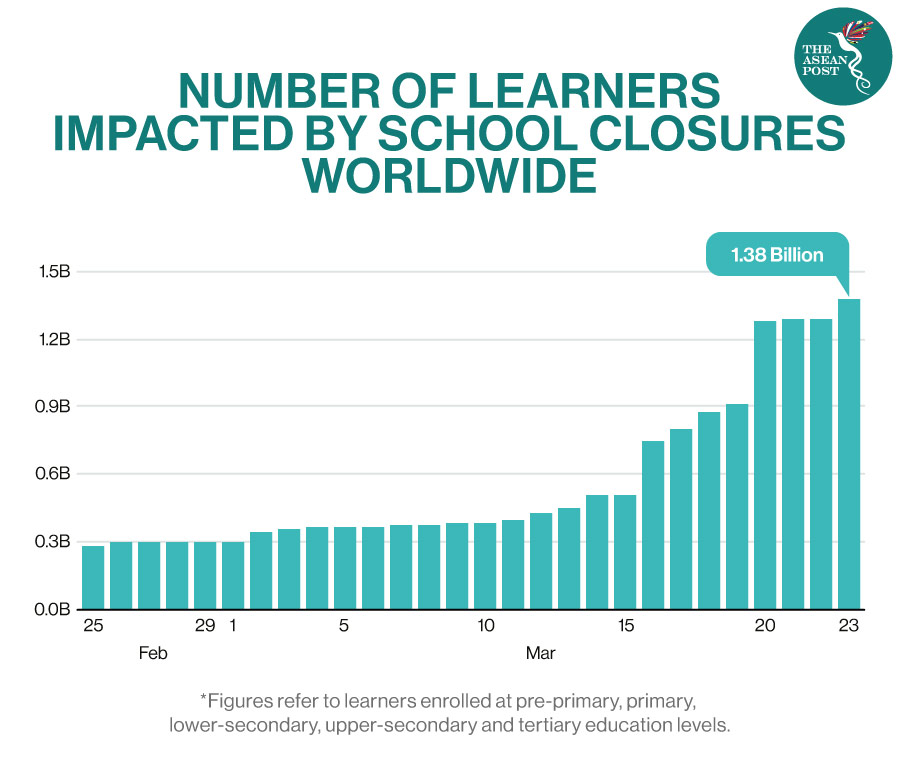

Unfortunately, the coronavirus crisis has severely impacted education systems around the world as millions of children and students are now out of school due to shuttered institutions. Towards the end of March when most countries had introduced COVID-19 preventive measures, over one billion students worldwide were affected.

Although some countries have reopened schools, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) estimates that more than 500 million learners are still affected by the pandemic.

As a result of school closures, many institutions are now offering online learning to their students. Unfortunately, not everyone has the ability to opt for this, which then highlights the digital education divide in many developing and least developed countries.

“Global Education Emergency”

Henrietta Fore, executive director of the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) said that the disruption to schools caused by the pandemic is a “global education emergency”. She added that at least 24 million students are projected to drop out of school due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

“We know that closing schools for prolonged periods of time [has] devastating consequences for children. They become more exposed to physical and emotional violence. Their mental health is affected. They are more vulnerable to child labour, sexual abuse, and are less likely to break out of the cycle of poverty,” explained Fore.

A recent survey by the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) and UNICEF revealed that the number of students from poor communities in Malaysia’s capital city Kuala Lumpur and its surrounding areas returning to the classroom is dropping at an alarming rate.

“Children have returned to school, yet seven percent of upper secondary-age children (nine percent for boys) in these families reported not returning to school,” noted the organisations.

The study found that one out of five respondents said that their children had lost interest in school or are demotivated, while cost was also found to be the biggest factor contributing to the issue. One in two respondents said that they struggled paying for tuition fees while 50 percent found it difficult to provide pocket money for their kids.

According to local media dated last September, the Philippines is also reporting a drop in school enrolments for the current academic year, with a nine percent decline compared to the previous school year (2019-2020).

“For now, we consider these 2.3 million as dropouts… What we don’t want to happen is to have a permanent dislocation of children, and instead of studying, they would permanently just go to work,” said senator Sherwin Gatchalian.

A similar situation can also be observed in many other developing nations.

Room to Read, an organisation focused on girls’ education and children’s literacy conducted a survey of 28,000 girls across Bangladesh, Cambodia, India, Lao, Nepal, Sri Lanka, Tanzania and Vietnam with disheartening results. It was found that 42 percent of the girls surveyed reported a decline in their family’s income amid the pandemic and that one in two girls surveyed was at risk of dropping out of school.

“The worrying trend is that the reopening of schools doesn't automatically mean that all children will be back in schools," said Francisco Benavides, regional education adviser at UNICEF East Asia and Pacific. “The pandemic has a high economic impact for the region. If girls don't have access to learning opportunities, it's very likely that the families and society will be less able to adapt to economic shock.”

Related Articles: