In 1990, energy joint venture firm Shell MDS issued the first corporate sukuk in Malaysia worth an estimated US$30-35 million at the time and since then, the country has not turned back. The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) member remains at the forefront of the global sukuk market till today.

What is a sukuk?

Sukuks represent certificates of equal value and act as an evidence of a Shariah-compliant investment that’s endorsed by the Shariah Advisory Council. They are essentially Islamic bonds but differ from their western counterparts in one key aspect – a sukuk generates returns and not interest or “riba” which is not allowed under Islamic law.

When an investor purchases a conventional bond, the money is loaned to the bond issuer for a fixed period of time. At the end of the bond maturity date, the investor should be paid back the full amount plus interest. However, since Islamic law prohibits interest – as money is not allowed to make money – the structure of a sukuk differs from that of regular bonds.

The money from a sukuk investor is used to generate profit from the purchase of assets or funding of projects that are compliant with Shariah law. Sukuk holders will hold a title – bearing evidence of ownership of the asset involved – and are periodically paid a share of the profits generated from these ventures. This profit to the investor is dependent on a predetermined ratio which is agreed upon between the investor and the issuer.

Sukuk potential in Malaysia and Indonesia

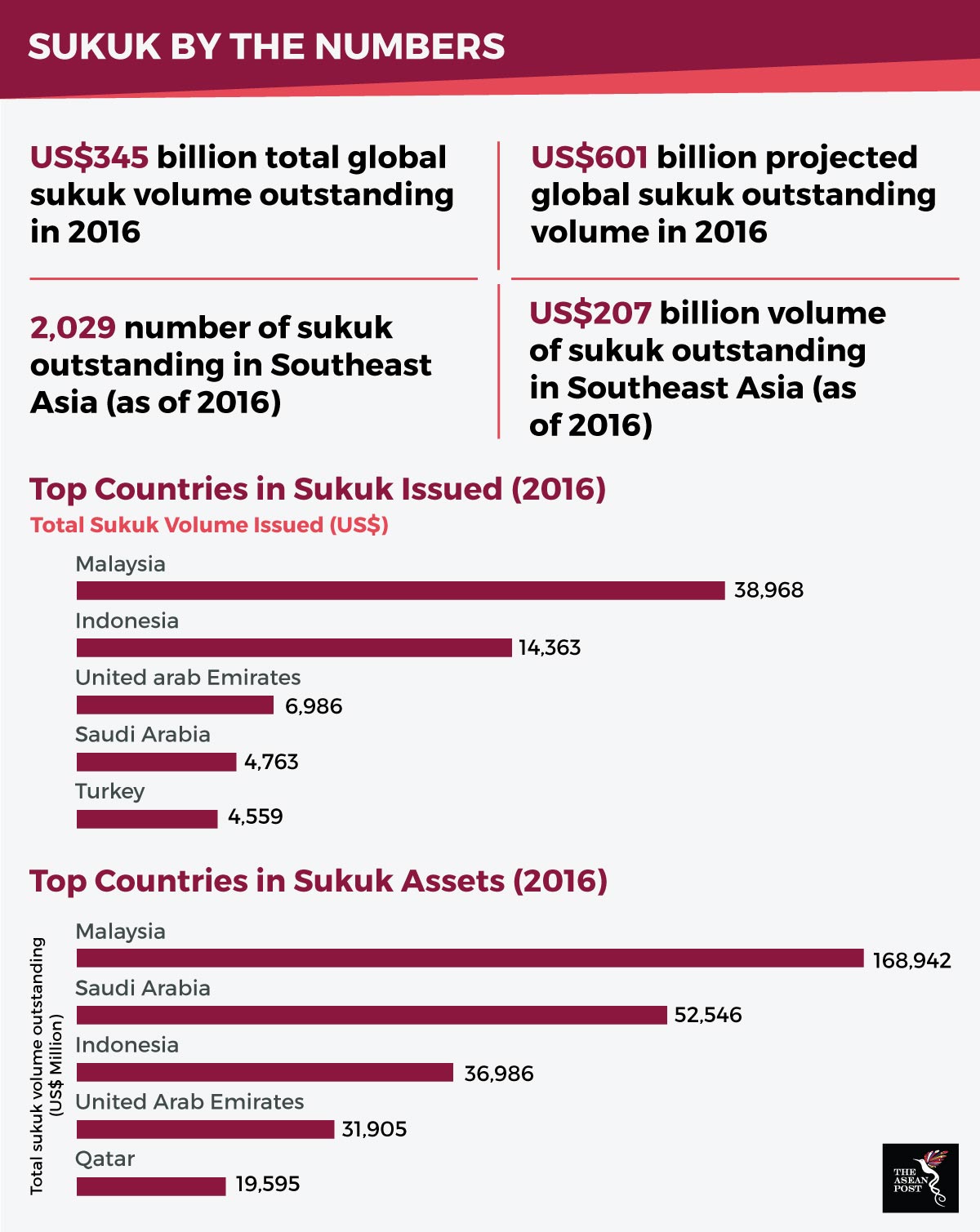

According to the 2016 Islamic Finance Development Report released by Thomson Reuters, Southeast Asia remains the largest region in terms of both, sukuk outstanding (US$206 billion) and sukuk issuance (US$54 billion). Of this number, Malaysia made up 82 percent of sukuk outstanding (US$168 billion) and 72 percent (US$39 billion) of sukuk issuances – representing 46 percent of global issuances.

Malaysia has an existing framework for sukuks as per its Capital Market Masterplan. The plan is to help facilitate greater retail participation in the debt capital market which includes sukuks. Credit rating agency, RAM Ratings said in a statement that it expects quasi-government heavyweights like DanaInfra Nasional – a government backed infrastructure financing entity – to bolster local currency sukuk issuances thanks to government infrastructure projects.

“We anticipate DanaInfra’s sukuk issuance to increase significantly in 2018, driven by the funding requirements for the MRT Line 2 and the Pan Borneo Highway,” said Ruslena Ramli, RAM’s Head of Islamic Finance.

Besides Malaysia, Indonesia too has been reaping the benefits from its issuances of sukuks. As of 2016, it had US$37 billion outstanding and US$14 billion in issuances – making it the third highest globally with regard to sukuk outstanding and second highest in terms of sukuk issuances.

Indonesia’s financial authority is actively pursuing a sukuk masterplan that was unveiled in September, 2017. It aims to raise sovereign sukuk issuance to 50 percent of total debt issuance over the next 10 years. This is aimed at bolstering financing for government projects in education, infrastructure and agriculture among others. It is also to encourage Indonesian companies to provide more Shariah-compliant investment tools which would help meet their liquidity requirements.

Sukuks go green

With climate change and environmental issues fast becoming major concerns globally, projects in renewable energy and other environmental assets are lucrative areas for investments. Just like there are green bonds – where the money raised is used to finance businesses or projects that have positive environmental and/or climate benefits – there are green sukuks which are the Shariah compliant versions of their western counterparts.

The first ever green sukuk was issued by Chinese owned Tadau Energy in the Malaysian debt capital market. The ringgit denominated issuance was worth RM250 million (approximately US$65 million) with a tenure of 2 to 16 years and its green sukuk framework was certified by the Center for International Climate and Environmental Research (CICERO).

Over in Indonesia, the first ever sovereign green sukuk issued was worth US$1.25 billion. The proceeds from this green sukuk would be channelled to climate or environment-related projects, such as renewable energy, sustainable transport, waste management and green buildings.

Green sukuks are a brilliant way of bridging the gap between conventional and Islamic financing. Since it appeals to Shariah compliant investors, it also broadens the investment base of green financing which is integral to close the gap for the estimated US$3 trillion demand for additional ASEAN green investment between 2016 to 2030.

As Islamic finance continues to enlarge its footprint in the region, sukuks in general are fast becoming the investment instrument of choice for many investors. It is expected that demand for such Shariah compliant instruments will only skyrocket as we move into the future.