On 6 February, the world celebrated International Day of Zero Tolerance for Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) which aims to raise awareness and to eradicate the practice. Anti-FGM activists and organisations are calling FGM a crime against women and girls. Several countries such as the United Kingdom (UK) have made FGM illegal and it is considered a form of child abuse. Anyone who performs FGM in the UK can face imprisonment for up to 14 years. Despite objections by the United Children’s Fund (UNICEF) and the United Nations (UN) among others, FGM is still a common practice and prevalent in some parts of the world, including Africa and Southeast Asia. According to the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), in 2020 alone, 4.1 million girls around the world are at risk of undergoing FGM.

What is FGM?

According to the UK’s National Health Service (NHS), female genital mutilation (FGM) is a procedure where the genitals are deliberately cut, injured or changed. FGM is usually performed on young girls before they reach puberty, between infancy and the age of 15.

The World Health Organization (WHO) classified FGM into four different types.

Type 1 is the partial or total removal of the clitoral glans and/or the clitoral hood. Type 2 is the partial or total removal of the clitoral glans and the labia minora (the inner folds of the vulva), and/or the labia majora which is the outer folds of skin of the vulva.

Type 3 which is the most severe and also known as infibulation – is the narrowing of the vaginal opening by cutting and repositioning the labia minora, or labia majora, sometimes through stitching. Type 4 includes all the other procedures carried out on the female genitalia such as pricking, piercing, incising, and scraping the genital area.

FGM vs FGC in ASEAN

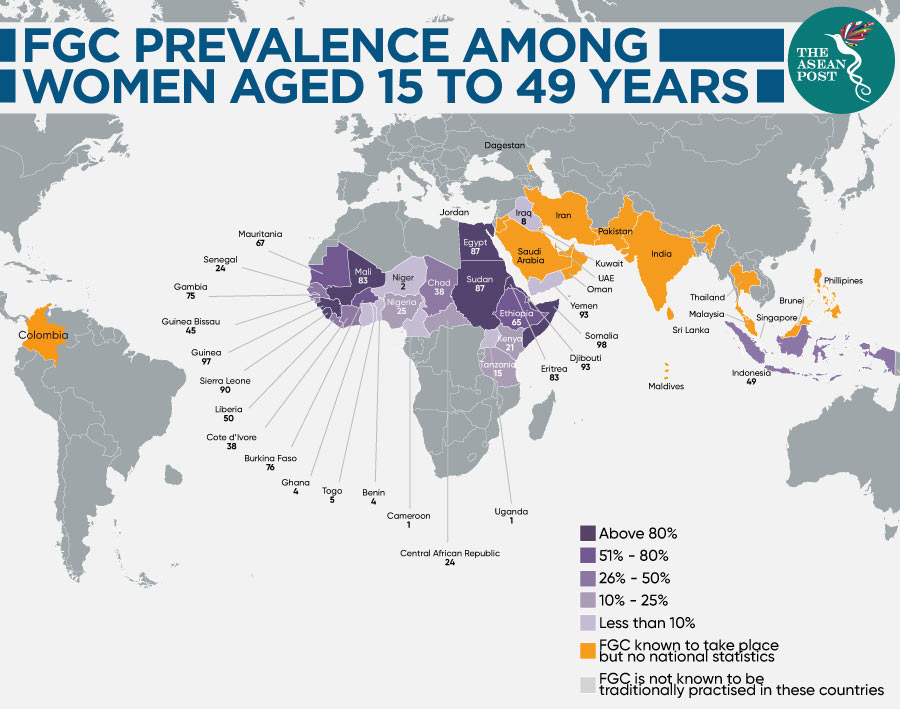

FGM is a common practice in Southeast Asia and is usually referred to as female genital cutting or circumcision (FGC) as the word ‘mutilation’ in FGM is considered demeaning. In some parts of Southeast Asia FGC has been normalised, and the ritual is seen as a tradition that has been around for generations. Female circumcision in ASEAN is commonly practised by the Muslim community in Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, Brunei and Southern Thailand as it is considered a religious obligation.

In 2009, a fatwa – which is a legal pronouncement in Islam, allowed the practice and made female circumcision mandatory except in cases where it is considered harmful to the girl in Malaysia. The Ministry of Health there also released a standardised guideline on the proper procedure of female circumcision, making sure that the operation is safe.

In 2016, Indonesia became the first Asian country to be included in the UN’s global report on FGM prevalence. It was said that half of the girls under the age of 11 had undergone circumcision in the country and it is sometimes offered as part of “birthing packages” in some hospitals. FGC is also legal in Brunei and Singapore, where a circumcision conducted by a health worker would cost around SGD20 - SGD35 (US$15 - US$26).

As claimed by the Orchid Project, an organisation which aims to end FGM – Brunei is more likely to conduct Type 1 or Type 4 female circumcisions. It usually involves a slit or a prick of the top of the clitoris. These types of female circumcision are also commonly practised in neighbouring countries, Malaysia and Indonesia. Malaysia’s Deputy Prime Minister, Dr Wan Azizah Wan Ismail rejected comparisons with FGM as no severe Type 2 or 3 mutilation occurs in female circumcision.

Hygiene and aesthetic appeal are said to be factors for FGC, according to the UNFPA. Based on reports, female circumcision is believed to be a way to control a woman’s sexuality and is seen as a part of a girl’s initiation into womanhood. Apart from that, many women cite religion and culture as the main reasons for the ritual.

Ismail Yahya, a former Islamic jurist in the east coast state of Terengganu in Malaysia, questioned the practice of FGM as there are no religious texts to support female circumcision. A paper by Isa et al., (1999) titled, ‘The practice of female circumcision among Muslims in Kelantan.’ – another east coast state in Malaysia, suggested that “there is evidence that in at least some parts of the Muslim world, FGM is a practice of culture, not of religion, because it was practised even before Islamisation took place.”

No health benefits

The WHO has stated that FGM carries no health benefits and is harmful to females. Immediate complications can include severe pain, excessive bleeding, genital tissue swelling, urinary problems, infections and even death. FGM also comes with long term effects such as menstrual problems, sexual problems, increased risk of childbirth complications and psychological problems.

According to media reports, the practice of FGM has decreased in recent years as the UN strives for a total elimination of FGM by 2030, following the spirit of Sustainable Development Goal 5.

FGM/FGC has been around in Southeast Asia for generations. Although it is known to be practised by Muslims in ASEAN, the tradition of female circumcision is not exclusive to the community. Many cultures have also adopted the practice. FGM/FGC continues to be a controversial topic in Southeast Asia as the decades long ritual has become embedded in the way of life of the region’s peoples. It is hard to ascertain if the UN’s goal of eradicating this established practice in ASEAN can be achieved.

Related articles: