Myanmar, once known as Burma during colonial times, is perhaps the most controversial member state in ASEAN today.

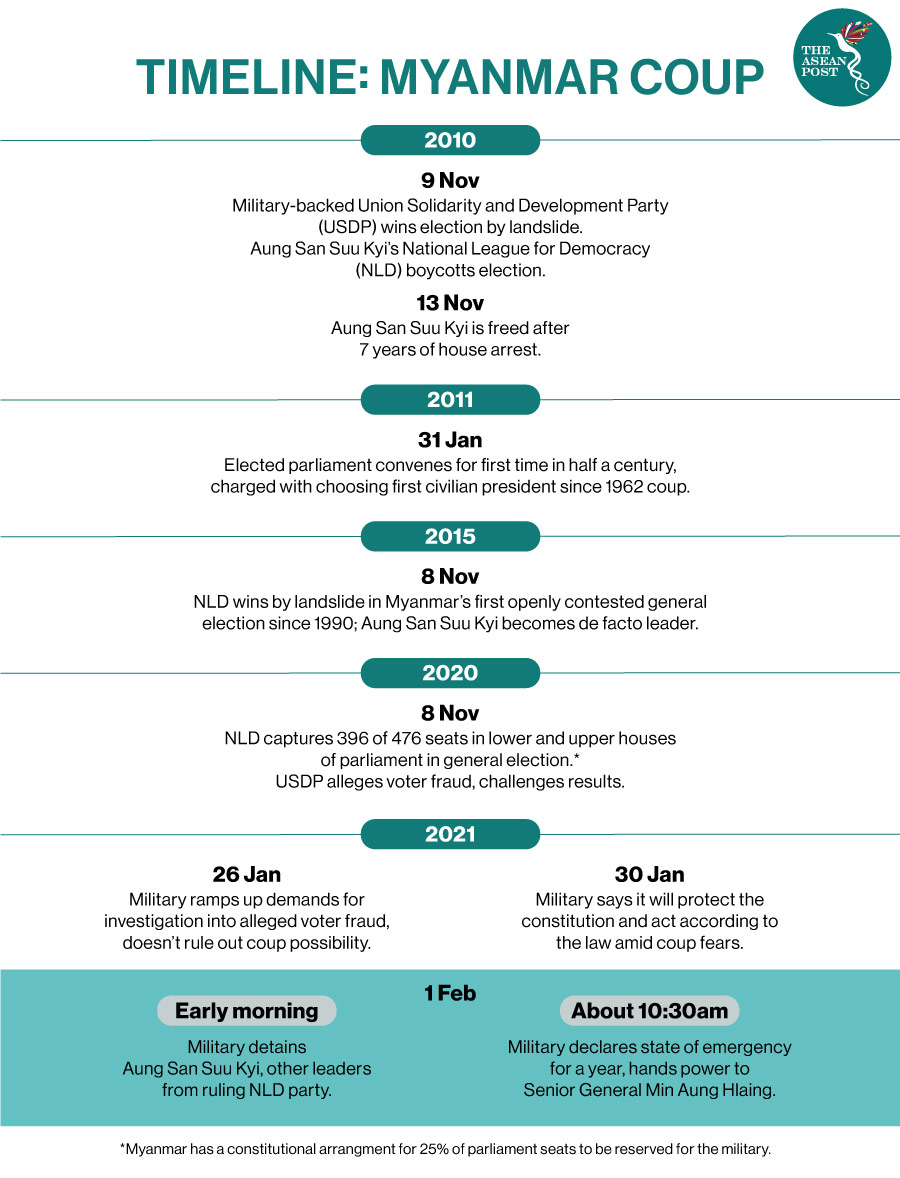

What happened on 1 February, 2021, where the Tatmadaw or Myanmar’s military seized power in a coup against the elected government of Nobel laureate Aung San Suu Kyi, who was detained alongside some senior leaders of her National League for Democracy (NLD) party, is without a doubt a backlash and a major setback of the budding and nascent democratisation process taking place in the country.

This political crisis has received international condemnation from the West, as well as from some Asian countries and the United Nations (UN). The European Union (EU) has warned Myanmar’s generals of possible economic embargoes and other forms of sanctions. Whereas, Asian countries like China and Bangladesh have called on all parties in Myanmar to exercise restraint, respect the constitution, and to uphold “peace and stability”.

The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) on the other hand, of which Myanmar is a member state, called for “dialogue, reconciliation and the return to normalcy.” However, some ASEAN member states like Thailand, Malaysia, and the Philippines, have treated the on-going civil unrest in Myanmar as an “internal affair” thereby shadowing a “hands-off policy” towards the political turmoil in the country.

“Hands-Off” Policy

The “hands-off policy” or so-called “wait and see” approach of some ASEAN member states towards the on-going political turbulence in Myanmar, is a product and a consequence of ASEAN’s principle of “non-interference,” – a normative framework meant to restrain, restrict and discourage ASEAN member states from meddling in each other’s domestic affairs.

Thus far, ASEAN has historically espoused a policy of non-interference in the internal affairs of its member states.

The non-interference principle protects and guarantees ASEAN member states’ independence and sovereignty. The said principle is reinforced by a decision-making process that is based on “consultation and consensus” and a focus on the peaceful resolution of inter-state disputes, but remains silent on resolving intra-state conflicts of ASEAN member states that more or less have regional repercussions and impacts on regional security, more particularly human security.

To note, the ASEAN principle of non-interference is an original core foundation that governs how ASEAN member states conduct regional relations with each other. The principle is stipulated in several ASEAN documents including the Bangkok Declaration of 1967, which was reiterated in the Kuala Lumpur Declaration of 1997 and further reinforced in the 1976 Treaty of Amity and Cooperation in Southeast Asia (TAC), where the said principle is explicitly referred to as one of ASEAN’s fundamental principles.

Hence, time and again, the principle arguably has been the centre of debates, controversies, and arguments, being pointed to as ASEAN’s handicap as to why it is restricted to respond collectively to the internal political problems and challenges of its member states. Such limitations in the conduct of ASEAN is reflected in how it had done little to respond to the repressive and dismal political situation in Myanmar since the inception of military rule in the country in 1962.

Exemption To The Rule

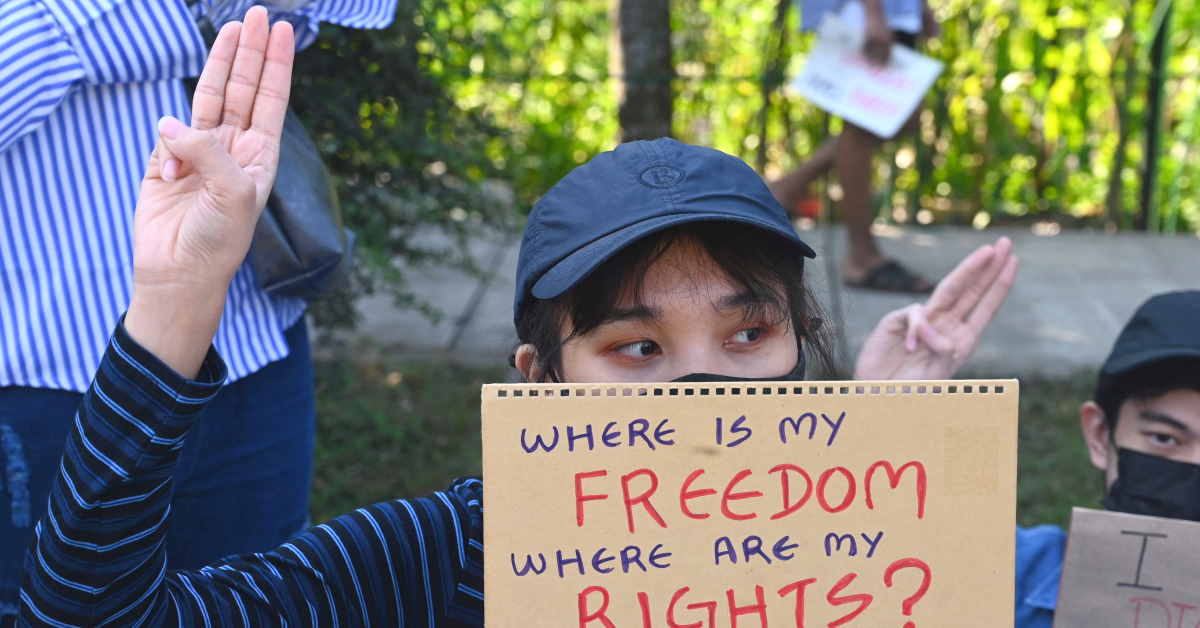

Nevertheless, arguably, the non-interference principle of ASEAN in the case of Myanmar should be challenged as its citizens demand for democracy to take root in their country which has been pillaged by the military since 1962.

If one were to take a closer look, the case of Myanmar should not be anchored on “state-sovereignty” alone, but must be fastened more on the issue and concern for the “human security” of the Burmese people. The unfolding political turmoil in the country brought about by the military coup is further aggravating an already dismal situation in the country at the time of the coronavirus pandemic. With the number of COVID-19 cases rising, the country’s response to the pandemic has been very limited, affecting not only the economy but also threatening the lives of locals.

Given the dismal human security situation in Myanmar coupled with the humanitarian problem associated with the Rohingya, the Myanmar case should not be treated by ASEAN and its member states as an “internal or domestic affair,” but rather as a regional concern if not an international quandary that needs ASEAN’s and the international community’s attention.

Although there is no doubt that everyone will agree with the longstanding importance of a non-interference policy in the bloc’s conduct of regional affairs, the principle should at least, if possible, not be taken by ASEAN in absolute terms in the case of Myanmar.

ASEAN should at least tackle the situation using a more flexible approach that would allow open discussion on any urgent action that its member states can take to de-escalate political tensions, prevent bloodshed and to put a stop to hostilities perpetrated by the military junta. This could help prevent the loss of life and the further deterioration of the economic and political situation in the country.

What Can ASEAN Do?

ASEAN should treat the Myanmar issue as a matter of utmost urgency precisely because of two important considerations.

First, it is imperative that ASEAN responds to the current human security vulnerabilities in terms of welfare and safety of the people of Myanmar from political persecution and the threat of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Second, is to avoid the recurrence of spill-over effects that the on-going political turmoil in Myanmar may produce, which could negatively impact neighbouring countries.

For instance, if the crisis escalates to an unprecedented level and is not resolved peacefully, it will more or less produce similar cross-border repercussions exemplified by the aftermath of the 1988 student uprising and the May 1990 elections.

These may include the exodus once again of Burmese refugees, political asylum seekers, illegal migrants, and the Rohingya to neighbouring countries like Thailand, India, Bangladesh, and Malaysia to say the least; putting a considerable strain on the governments of these countries.

If these possible cross-border issues and repercussions are to be prevented from happening again, ASEAN member states must deal with the Myanmar debacle squarely. ASEAN can at least put some pressure on the military junta to first and foremost respect the results of the 8 November, 2020 elections, release Suu Kyi and all political detainees, then go back to the negotiating table and discuss with the legally constituted and democratically elected members of the NLD on how they can work together to resolve their differences.

If done properly, this will to a degree bring back some elements of normalcy to Myanmar.

Also, the bloc could send a high-level ASEAN delegation to Myanmar to persuade the military junta to establish open political talks and dialogue with the NLD. Likewise, ASEAN should act in the soonest possible time to bring all concerned parties to the negotiating table before the situation deteriorates further.

If ASEAN takes these progressive steps, other international organisations and nations would bestow on it a much greater level of respect, and ASEAN will gain more relevance and credibility among the region’s citizens and the broader international community.

Conclusion

Given the prevailing disturbing and alarming political climate at the moment, the Myanmar issue is a matter of urgency.

ASEAN and the rest of the international community must not allow the political situation in Myanmar to further deteriorate as it would lead to the worsening of an already dire situation for its people.

ASEAN member states must heed the call of the people of Myanmar for help and assistance. Their safety and security heavily rely on the continued support of the international community.

On this note, ASEAN should affirm its commitment to democracy and not turn a blind eye; rather it must help to forge solidarity with the people of Myanmar once again as they struggle for freedom, liberty, and democracy.

Related Articles: