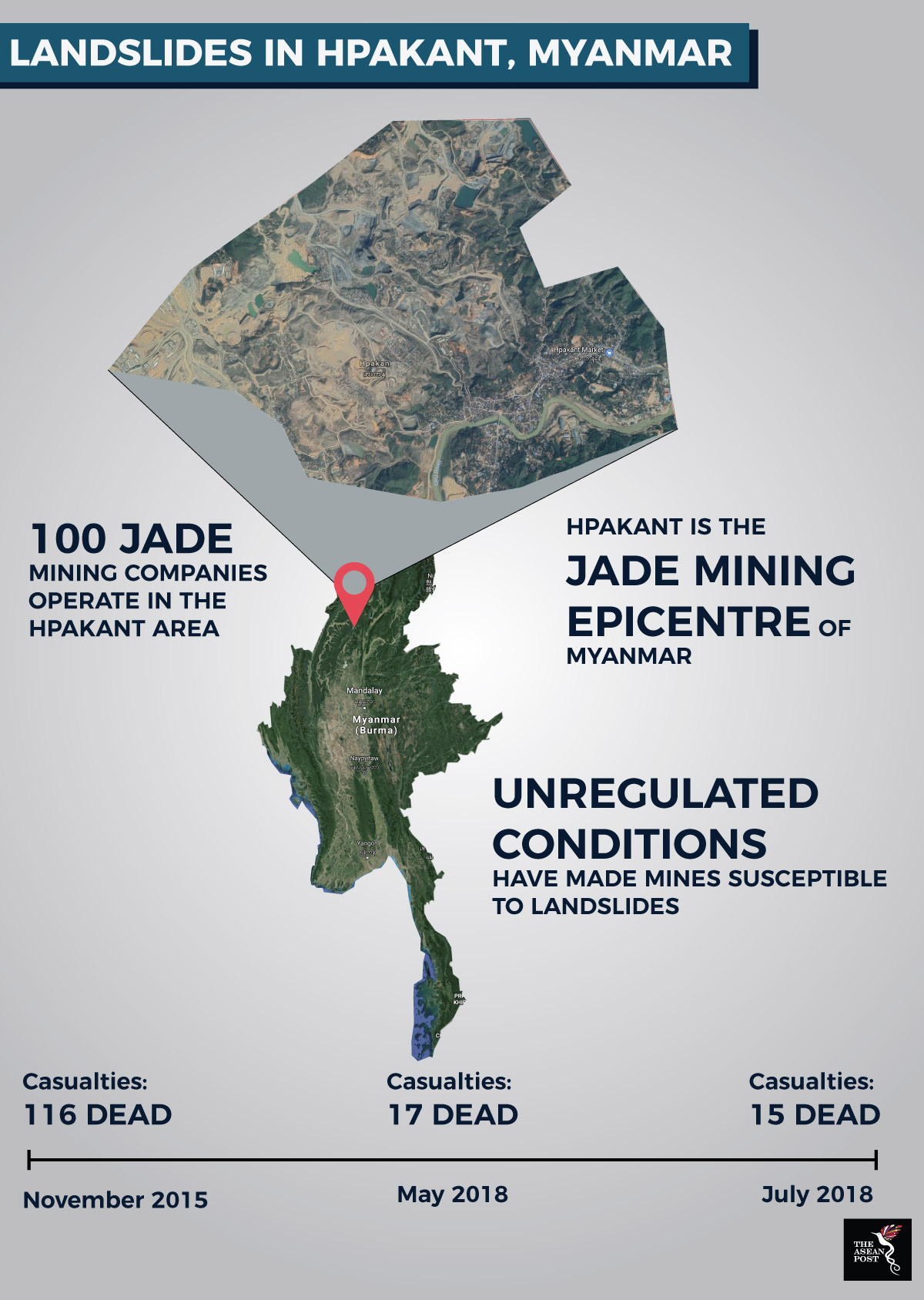

Earlier this week, at least 15 people were killed in a landslide at a jade mine in Hpakant Northern Myanmar. State media and officials revealed that 15 bodies were retrieved from the site at Lonekhin village but rescue operations are still ongoing and there are fears that more people may be trapped under the debris.

This isn’t the first time that a tragedy like this has hit the jade mines of Myanmar. Jade mining in Myanmar is lucrative but at the same time also unregulated and extremely unsafe. Previously in May, a landslide at another jade mine killed 17 people. However, the worst reported incident was in November 2015, when more than 100 people were killed in a single landslide.

Many of these tragedies occur in Hpakant, located 950 kilometres north of Yangon which is also the main hub for jade mining in the region, if not the world. It is estimated that Myanmar is the source of more than 70 percent of the world’s supply of high-quality jadeite. For Myanmar, jade trading is essential to its economy, contributing almost half of its gross domestic product (GDP). According to Global Witness, an organisation that strives to expose corruption and environmental abuse, Myanmar’s jade production was worth US$31 billion in 2014. In the previous decade alone, it is estimated that Myanmar’s jade production was worth up to US$122 billion.

Despite being a multi-billion-dollar industry, workers in Myanmar’s jade mines have to put up with appalling conditions. To make matters worse, the government there also turns a blind eye to the situation. It is estimated that the 300,000 or more people – many of whom are migrants – who come to North Myanmar with the hope of cashing in on precious jade stones are forced to live in squalid conditions. When mining for jade, these people work in mines with little or no protection along with the spectre of a landslide always looming over their heads.

Sources: Various sources

Sources: Various sources

The “Wild West” conditions on the ground in Myanmar’s jade mines and trading industry is due to the institutional environment that the industry operates in. The jade economy in Myanmar is controlled by a shadowy and corrupt network consisting of Myanmar’s military elite, Chinese shell companies and even some multi-national companies. To make matters worse, many of the jade stones are also smuggled across the border into neighbouring China.

Prior to Myanmar transitioning into a democracy in 2016, a Global Witness investigation revealed the extent of corruption that occurs in the jade trade. The investigation revealed that key figures of the military junta at the time were involved in multi-million-dollar deals. Other reports have also shown that big buyers from countries like China and Taiwan have figured out methods to avoid paying taxes for jade. Global Witness reported that US$6.2 billion in mine site tax was lost in 2014 alone.

While Myanmar might call itself a democracy after the elections in 2016, nothing much has changed in the jade trade. Although reforms were enacted with some prominent people being arrested as a result, many observers have labelled such moves as just superficial.

Jade mining is also linked to growing tensions between the government and Kachin state which has long sought autonomy and self-determination. The conflict between the Kachin Independence Army (KIA) and the Myanmar government has been on and off for more than 50 years. This year has seen a dramatic spike in violence, with over 10,000 people displaced from Kachin state since January. Some have argued that the Myanmar government refuses to give Kachin self-determination or even a fair peace deal because that would mean companies currently operating the jade mines would have to leave.

The two landslides that have happened in the past two months are evidence that not much has changed since Aung San Suu Kyi was elected State Councillor. Myanmar’s participation in the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) to allow for greater transparency on how the country manages its natural resources is commendable but not enough. There needs to be tighter regulations and proper enforcement. Failing which, the people who work in the mines would continue to be exploited while the elite keep on enriching themselves.