Myanmar is expected to begin the long-awaited overhaul of its 60-year old Yangon Central Railway station in mid-2018.

The project is estimated to cost around US$2.5 billion, and will also include new developments of office buildings, retail outlets and residential buildings in the area surrounding the station. The project and associated developments are expected to take eight years to complete.

"It is a tremendous project that will create new opportunities for both, local people and the business community," commented U Yang Ho, chairman of the real estate conglomerate Mottama Holdings to the Nikkei Asian Review in a recent report. Mottama Holdings is one of the developers in the re-development of Yangon Central Railway.

"We believe that this project will become the primary international investment project contributing to Myanmar's economy, attracting international investors and creating a new centre of attraction for Yangon," he added.

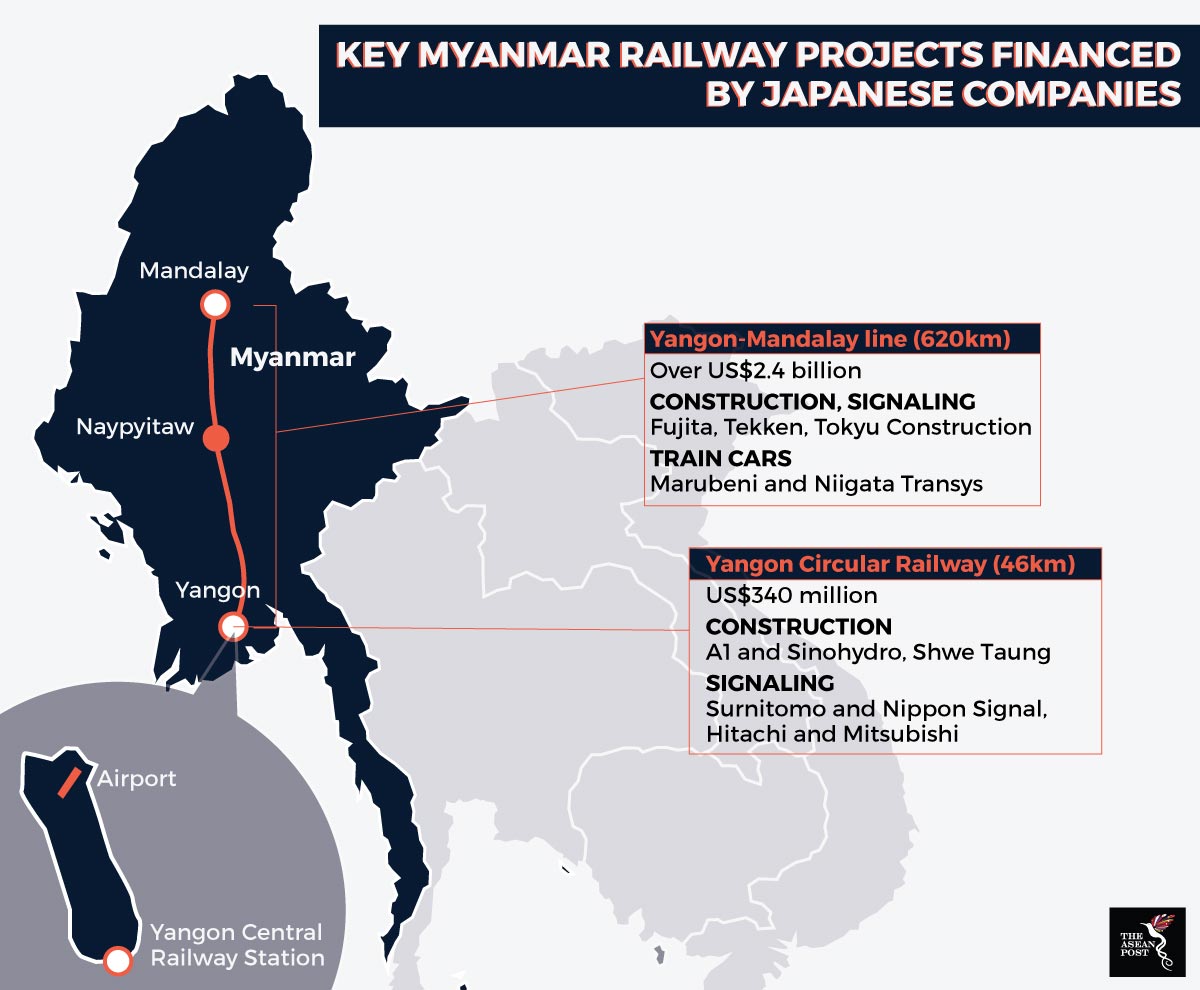

Upgrades to the Yangon Circular Railway are already underway and are due to be completed around March, 2019. There are also plans to re-develop a longer, 620-km railway line between Yangon and Mandalay. Construction work for this line is also expected to begin in mid-2018.

Senior general manager of Myanma Railways, Ba Myint, said that more than 47 million passengers take the train each year, more than two thirds of whom ride Myanma Railways routes. This number is expected to triple to 260,000 by the time renovations to Yangon Circular Railway are completed.

Source: Nikkei Asian Review, 2018

Myanmar needs better infrastructure to create a more attractive business environment, but the policy reforms required to encourage such infrastructure investment remain slow to come. Foreign investors are still awaiting the passing of a law that will enable foreign companies to own a minimum 35% stake in local companies. This being just one example of a measure that will provide local companies with much-needed funding to develop local infrastructure projects. Myanmar’s government possesses one of the lowest tax-rate structures in the region and can ill-afford to pay for these projects by itself. The last thing it needs is to lose out on foreign investors.

The policy paralysis has already caused short-term business confidence to plummet from 73% in 2016 to 49% in 2017, according to a joint survey by the Union of Myanmar Federation of Chambers of Commerce & Industry, and global consultancy, Roland Berger.

Strong ties with countries such as Japan and Korea have procured funding for ongoing railway projects thus far. Japan, via the Japan International Cooperation Agency is contributing US$207 million out of the US$301 million cost of the Yangon Circular Railway project. Japan has also pledged US$100,000 to assist in building schools, healthcare centres, roads and bridges, among other infrastructure in Myanmar’s villages.

The Import-Export Bank of Korea has also pledged a loan of US$100 million to renovate other rail routes, including the Myitkina-Mandalay route.

Whether such progress in renovating existing railway infrastructure will extend to other types of infrastructure development will depend on whether there is a political will to progress beyond this point. Critics have criticised Aung San Suu Kyi’s government for prioritising socio-political issues over her country’s economic development.

Ongoing events in the Rakhine state have been detracting from Myanmar’s economy, to say the least. Economic growth fell from 7% in 2016 to just 5.9% in 2017. FDI inflows into Myanmar have been largely affected, falling from US$7.8 billion in 2016 to US$5.6 billion in 2017.

“We expected much economic growth in 2017 but we had crisis in the Rakhine state and it affected the potential arrival of foreign businesses,” said Hanthar Myint, chair of the National League For Democracy (NLD) economic committee to Asia Times in February, 2018.

Myanmar’s economic growth is expected to recover to 6.4% this year, according to the World Bank, but this also depends on whether reforms in supporting areas such as finance, business and energy regulations are also forthcoming. Myanmar currently stands at 171 in the World Bank’s Ease of Doing Business 2017 rankings, slipping down one notch from 2016. Only about 30% of its population currently has access to electricity, and Myanmar still suffers from a lack of skilled labour, as well as unreliable road networks.

“You can have a low labour cost,” commented Filip Lauwerysen of the European Chamber of Commerce to The Economist.

“But it is useless if you have the whole labour force doing nothing because of a power cut.”

Renovating its railway systems is a good step towards revamping the infrastructure landscape in Myanmar, but it is just a start. For Myanmar to achieve its full economic potential much more needs to be done.