There is a growing trend in ASEAN that is not so welcomed – obesity. The prevalence of obesity and being overweight among ASEAN’s citizens is increasing due to rising incomes, and urbanisation. It is also placing a strain on the region’s healthcare systems and government budgets.

An obese person can be measured by his or her Body Mass Index (BMI) which measures a person’s weight in relation to their height. An obese person would have a BMI higher than 30, whereas a normal BMI is between 18.5 and 24.9. However, BMI has its limits as it can either overestimate body fat in muscular athletes or underestimate body fat in older people who have lost muscle mass.

According to a report on obesity from Fitch Solutions Macro Research, Vietnam, Thailand, Singapore, the Philippines, Malaysia and Indonesia have seen a rise in the number of obese adults. The report recorded Vietnam as having the highest growth for obesity in ASEAN between 2010 and 2014 but still had the lowest number of obese persons in 2014. In the period of five-years, Vietnam’s obesity rate increased to 38 percent, whereas Indonesia and Malaysia were at 33 percent and 27 percent, respectively.

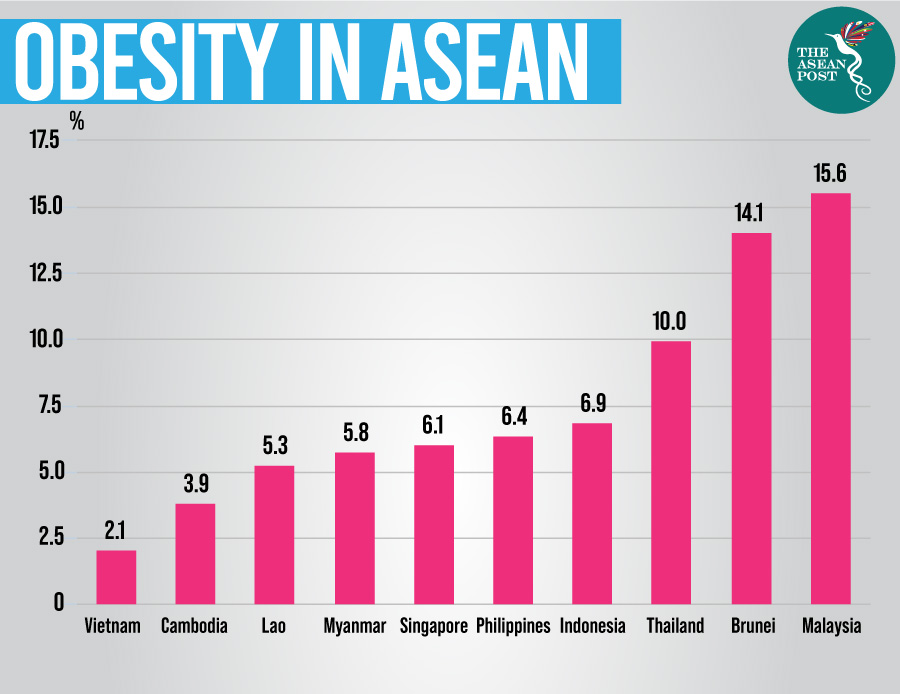

Based on a 2019 statistic from the World Population Review, Vietnam still has the lowest share of obese persons at 2.1 percent, far below Malaysia’s 15.6 percent and Brunei’s 14.1 percent. Yet, a study by Vietnam’s National Institute of Nutrition based on 5,028 students, discovered that 42 percent of children in Vietnam’s urban areas are overweight and/or obese, compared to 35 percent in rural areas.

Both Malaysia and Brunei have the highest prevalence of obesity among youths aged five and 19 years old. According to a United Nations International Children's Emergency Fund (UNICEF) survey, 12.7 percent of Malaysian children aged between five to 19 years old are obese, the second-highest in Southeast Asia behind Brunei’s 14.1 percent.

Indonesia also conducted its own Basic Health Survey (Riskedas) in 2018 which revealed a worrying trend of weight problems among Indonesian adults which has steadily increased from 2007 to 2018. The survey conducted on 1.2 million people found that about a third of Indonesians aged 15 and above had an unhealthy waist circumference.

Earlier this year, an Indonesian province put 50 overweight police officers on a crash programme of aerobics, swimming and jogging, to get them into better shape. "We think all the selected personnel don't have the ideal body weight," said spokesman Frans Barung Mangera. The two-week programme involved officers in East Java who were guided by nutritionists and medical experts.

Lifestyle changes

The World Health Organization (WHO) says that the rising costs of healthy food and food scarcity in underdeveloped nations is a contributing factor to obesity. But cultural and social norms are also contributing to obesity. The Fitch Solution report claims that “the improving economic standards in the region have brought about lifestyle changes, which in turn have led to a shift to more unhealthy diets,” leading people to adopt a diet of fast food that is low in cost and low in nutritional value.

Obesity can reduce productive years by a weighted average of between four and nine years across the ASEAN region. In addition to decreasing a person’s lifespan, obesity also affects their quality of life.

There are numerous health risks, including a higher risk of diabetes, heart disease and even certain types of cancer. Adding to this list, other risks can include osteoarthritis, sleep apnoea, kidney disease, stroke, and high blood pressure. In pregnant women, obesity can result in complications that can lead to health problems for the mother and child.

Furthermore, these health risks can result in mounting healthcare costs. Higher healthcare costs can imply low productivity which then could lead to economic losses. According to the 2017 Economist Intelligence Unit Limited Report, the economic impact of obesity is the highest in Malaysia with an estimated 19 percent of national healthcare spending. Healthcare costs from obesity in Indonesia ranged from eight to 16 percent of national healthcare spending. Vietnam and Thailand recorded the lowest in national healthcare spending with three percent and six percent, respectively.

The Economist report claimed that ASEAN countries lack granular data on obesity prevalence. Lack of data is a constraint on policy-making which can lead to untargeted health programmes. To design smarter policies, governments and stakeholders must understand where obesity is increasing in terms of ethnic groups, gender and region so that a more accurate trajectory for programmes can be obtained.

Targeting food intake also shows considerable promise, although exercise remains the top option for preventing and reducing obesity. Government intervention can positively help in tackling obesity. The Malaysian government for example, recently implemented a sugar tax in early July, on packaged sweetened beverages, from fruit juices to soft drinks. According to Deputy Health Minister, Dr Lee Boon Chye, citing examples from other countries, there is evidence that a “sugar tax actually helped to reduce the consumption of sugar.”

Dr Lee is optimistic that Malaysians can overcome the issue of obesity, noting that they are already making efforts to curb weight gain by opting for healthier and less-sugary choices.

“Even the syrupy drinks sold in stalls right now are not as sweet anymore, and I hope more food sellers will follow suit by putting less sugar in food and drinks,” he said. An effective food labelling system can also aid consumers in making healthier choices.

Related articles: