The Sidoarjo regency in East Java, Indonesia is known for its cottage industries which produce traditional prawn and fish flavoured crackers. However, tourists who flock there aren’t just lured by the promise of crunchy titbits, but come to see the largest mud volcano in the world.

The Sidoarjo mud flow, commonly called Lusi – an abbreviation of Lumpur Sidoarjo, “lumpur” means “mud” in Indonesian – has been spewing mud since it erupted in May 2006. While theories are abound as to the reason for this occurrence, it is a largely held view that it was caused by a mishap during the drilling process which led to the blowout of natural gas well. Schools and houses in the vicinity were destroyed and families were displaced while many others suffered from burn injuries.

While the Southeast Asian region remains giddy on its pursuit for energy to fuel the burgeoning industries, Lusi serves as a reminder that such a pursuit – especially through oil and gas explorations – comes with huge environmental costs.

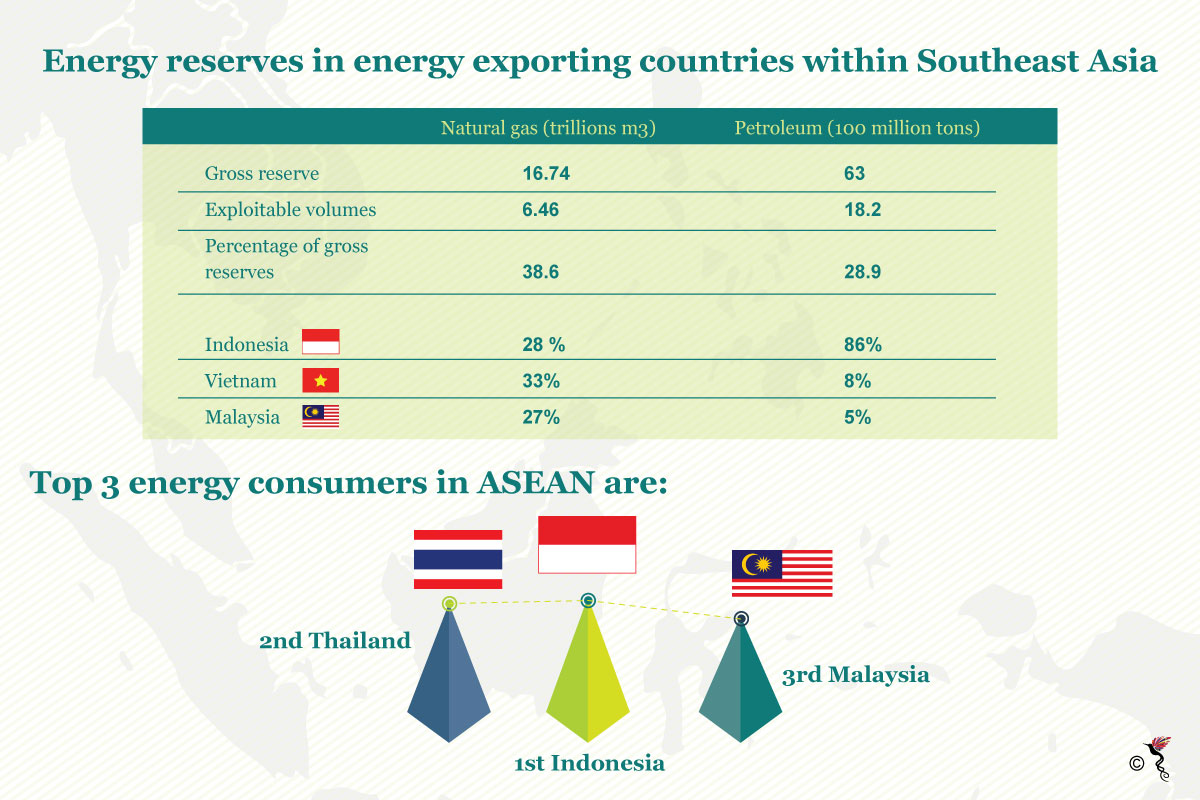

Energy consumption and energy reserves in the Southeast Asian region.

Impacts on the environment

At every stage of the oil and gas fuel chain, there is potential for action which can lead to hazardous consequences to the environment. The upstream or the E&P (exploration and production) sector requires the use of heavy machinery to “discover” oil and gas deposits and extract it from sedimentary rocks within the earth. This is accomplished using various techniques including exploratory drilling – such was the case with Lusi – special air guns and controlled underground explosions.

Oil drilling also brings muddy rock fragments or “cuttings” to the surface which are laced with toxic drilling fluids. Moreover, the extraction process also produces quantities of contaminated water or “produced water” which often contain lethal chemicals like mercury, benzene, lead and zinc that are treated before released back to the environment. However, operators often have to increase the salinity of the water before doing so which can be detrimental to the ocean’s ecosystem. Every gallon of oil brought to surface yields eight gallons of cuttings and produced water.

In the downstream sector, raw oil and gas products are further refined into goods of higher value. The processes involved consume large amounts of water which when released, can still contaminate the environment even after being treated. The soaring temperatures of this water or “effluent discharge” can negatively impair the surrounding biodiversity especially when funnelled in large amounts into nearby lakes or rivers. Chemicals used in these processes could also seep into the soil and affect groundwater sources.

Aside from that, natural gas also poses environmental challenges when it is burned off at well sites or vented straight into the atmosphere. The combustion releases carbon dioxide and water vapour, making the industry responsible for upwards of two billion tonnes of carbon dioxide emissions globally.

Stringent safety regulations in place

With the propensity for such immense risks to the environment, the industry is subject to very strict regulations. Every oil and gas player adheres to rigorous safety protocols supplemented by a moral obligation to not harm the environment as they ply their trade.

According to Go Home Safe, a company specialising in safety as well as pollution control within the oil and gas and marine industry, taking such safety measures would stop environmental degradation caused by the oil and gas fuel chain. Some of those measures are administrative controls in accordance with ISO 14001 standards, operational controls and engineering controls. ISO 14001 is an international standard for developing effective environmental management systems across industries. The latter two ensure proper management and the discharge of pollutants. Besides, there must be proper audit of the systems in place and a robust emergency response management plan for all activities that impact the environment.

The company reiterated that “all aspects of safety with regards to the environment are taken very seriously by oil companies from the very top to the bottom of the management hierarchy.”

While the risks are mitigated by stringent regulations, accidents which occur due to human errors or unforeseen circumstances can still have negative repercussions to the environment and the people who are dependent on it.

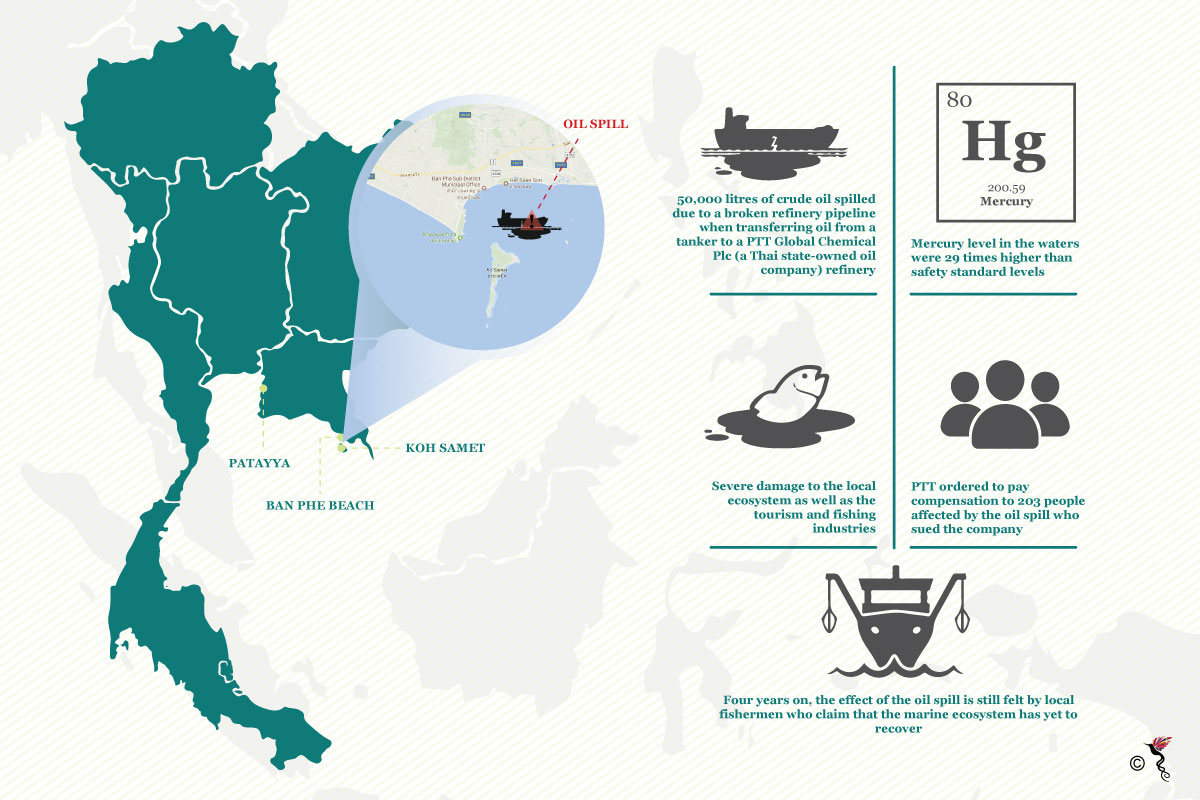

In 2013, 50,000 litres of crude oil spilled into the sea near Rayong, Thailand when a pipeline burst while transferring oil from an undersea well to an oil tanker, destroying much of the ecosystem and natural resources. This invariably impacted the nearby island of Koh Samet which relies heavily on tourism and fishing – especially more since, tourists often came for the exquisite seafood the place had to offer.

The location and details of the oil spill off the coast of Koh Samet in 2013.

Overcoming environmental damage

Phoumin Han, an Energy Economist with ERIA (Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia), in an email reply to The ASEAN Post said that the response to environmental damage could be reflected in the “environmental procedures and protocol.”

“Countries will need to establish all steps, precaution and safeguard, emergency response in case of accident (spill and others) and restoration of the environment through procedures based on the level of damages,” he added.

It is better still to be prepared in advance before facing such environmental challenges. Especially ones that have a direct impact on human life such as water pollution caused by the extraction of fossil fuels.

“Mitigation measures such as the minimisation of discharges to the sea (the so-called “zero-discharge” policy) and oil spill contingency planning to meet authority requirements and expectations should be established,” he suggested.

However, with regards to environmental regulations and standards, the devils are in the detail – specifically pertaining to implementation. Every ASEAN country has laws against environmental degradation, but the levels of enforcement differ from country to country.

“Frankly speaking, some ASEAN countries with weak governance system may not have a thorough assessment about this, and a project could go ahead more easily compared with countries with stringent environment regulations and standards,” Han remarked.

Echoing similar sentiments, the Director of the Institute of Sustainable Energy, Kumaran Palanisamy while admitting that the industry is highly regulated, relented that “implementation is a different story.”

“Oilfields in this region are drying up and oil exploration companies would have to go deeper in search of oil, at so called 'marginalised fields'. This would incur additional costs, hence, there is a probability for them to take shortcuts. This could mean damaging the environment in the process,” he told The ASEAN Post in a telephone interview.

Renewable energy for the future?

For those seeking refuge in the promise of renewable energy, there is hope but only a very minute one. According to the IEA (International Energy Agency), energy demand in Southeast Asia is projected to rise by 80 percent to just below 1,100 Mtoe (million tonne of oil equivalent) by 2040. Only 21 percent of energy demand in 2040 will be constituted by the plethora of renewables including hydropower, solar and wind while fossil fuels account for the remainder.

The agency’s estimates show that oil demand would rise 44.7 percent from 4.7 million barrels per day in 2014 to 6.8 million barrels per day in 2040. Meanwhile, natural gas use is likely to grow by almost 67 percent to 265 billion cubic metres. Both scenarios are driven by increased industrial demand.

This means that fossil fuels are here to stay and accordingly, the oil and gas industry will continue to be at the forefront of producing energy for regional consumption.

Going back to Lusi – the man-made mud volcano in Indonesia – until today, it continues to spew mud to the surface, although not as much as it used to, nine years ago. Now, it has become a rather bizarre tourist attraction. Nevertheless, its existence doesn’t negate the harsh reality that oil and gas exploration is necessary to feed our growing appetite for energy. But that appetite comes at a price, borne by our environment.