Southeast Asia has abundant energy resources but is generally slow to diversify its energy mix to include renewable energy (RE) sources, according to the ‘Renewable Energy Market Analysis – Southeast Asia’ report by the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA). This is due in part to problems accessing adequate financing for such projects. Southeast Asian countries would need to invest up to US$290 billion in order to secure 23% of primary energy needs from renewable sources by 2025, according to 2016 findings by the IRENA.

Currently, the need for investors is mismatched against a low supply of bankable renewable energy projects in the development pipeline. Whereas investors need assurance that financial risks are identified and managed, checks and balances are at present inadequate due to the lack of regulatory structures. Financial structures which have only been cognizant in handling fossil fuel projects so far are less equipped to handle RE projects, resulting in a high volume of unbankable projects turned out so far. Because local banks have completed so few RE projects, they can provide little data against which benchmarking guides can be set for commercial banks to gauge investment risks.

On top of that, a lack of clarity in the actual risk also exists because local contractors don’t have experience in handling RE projects. This makes it difficult for them to structure projects in such a way as to manage risk well. It is due to all these factors that renewable energy projects in Southeast Asian countries simply pose less attractive returns for global investors compared to asset classes elsewhere.

What makes a project bankable?

According to analysis by the Asia Pacific Risk Center, an unbankable project to private investors is one that is completely unfeasible because it requires investors to take on the large risk of betting on the certainty of government involvement, since these projects would not otherwise work.

Slightly up the scale are low-quality bankable projects, which are feasible so long as the investor is willing to undertake high local risks such as those posed by volatile political conditions, high foreign exchange risks and a lack of infrastructure.

Power Purchase Agreements (PPAs) that are denominated in local currency are examples of low-quality bankable projects. PPAs usually refer to contracts between a government agency and private utilities company of which a third party, who is usually the investor, also becomes privy. This is according to financial education website Investopedia.

Vietnam’s introduction of a template PPA for solar projects for instance, was declared unbankable by Baker Mackenzie in 2017 despite including a conversion of feed-in-tariff (FiT) rates to US dollars. According to Baker Mackenzie, this was because it had failed to provide for adjustments in the event of exchange rate fluctuations, inflation risks and changes in the consumer price index from time to time.

Designing bankable PPAs also means providing adequate protection for investor interests should they choose to exit a project earlier than according to scheduled completion dates. In terms of the unbankability of Vietnam’s solar PPA template, Baker Mackenzie further noted that it was unfair for failing to provide for an outstanding debts settlement mechanism with regard to a private investor’s liabilities should the monopoly utility, Vietnam Electricity Corporation (EVN) chose to exit a solar financing deal earlier.

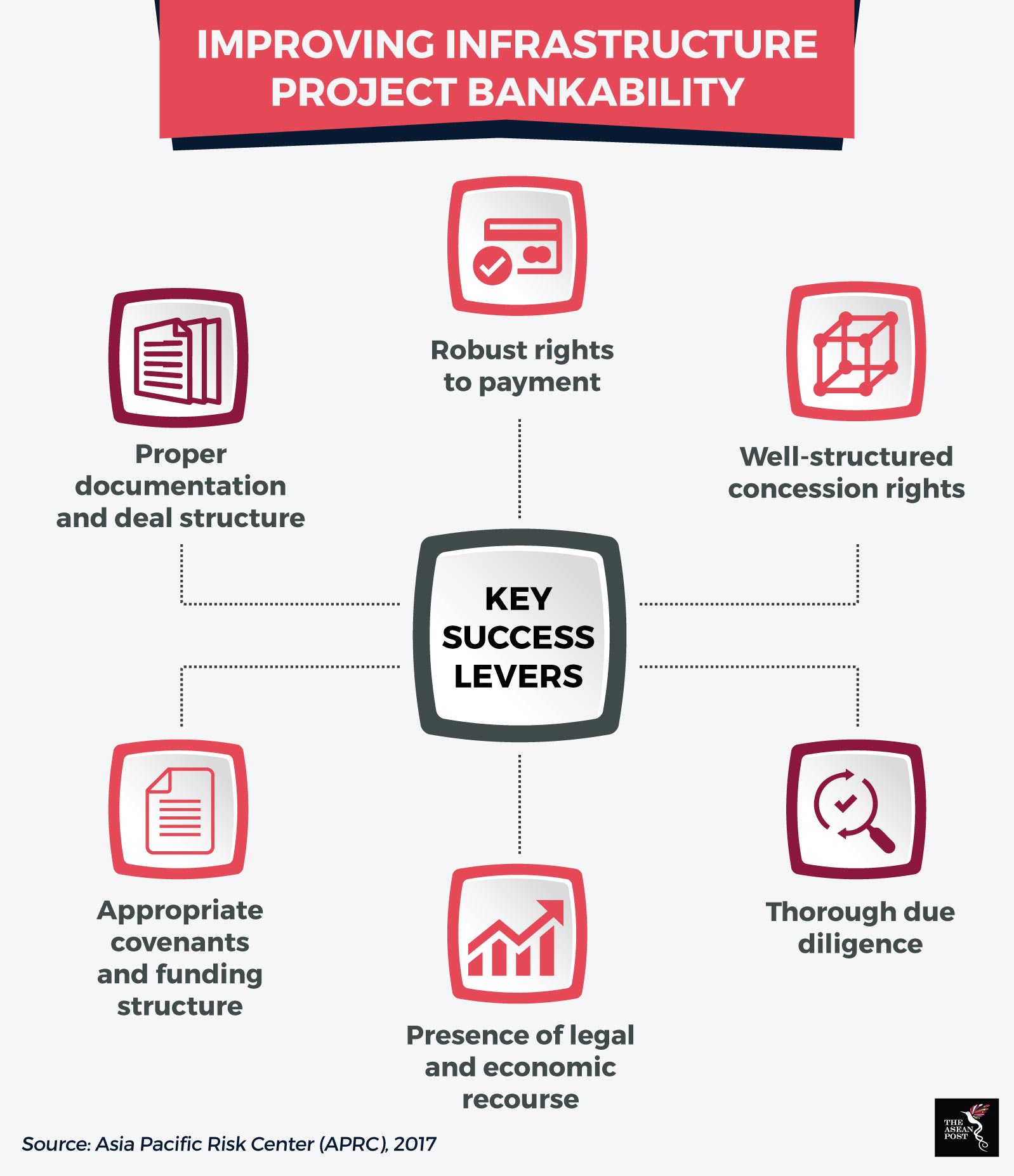

As such, a good start for Southeast Asian countries would be to ensure that they present proper documentation and deal structures to investors, with regards to renewable energy projects. Deal structures include the inputting of specific phases and timelines into projects so that progress can be effectively monitored and regulatory requirements adequately met, among other things. Financing can also be structured in such a way as to be disbursed only once project milestones have been completed. Streamlining the entire deal structure would increase certainty, minimise project delays and encourage investor confidence.

Baby steps are sufficient for now, since RE project unbankability problems is likely to be an issue that can only be overcome in the long term. What matters for now is that any steps taken are completed well, because they will set the groundwork for the future of renewable energy in Southeast Asia.

Recommended stories:

Can China’s militarisation of the South China Sea lead to armed conflict?

Need for regulation grows in tandem with e-payments push in Southeast Asia