Overseas remittances contributed US$31.29 billion to the Philippine economy last year, according to data released by the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP) in February 2018. Even with the recent foreign policy ban on workers to Kuwait, this seems unlikely to hamper the volume of remittances back home.

Remittances are defined by the financial education website Investopedia as the funds sent by an expatriate to his/her country of origin via wire, mail or online transfer.

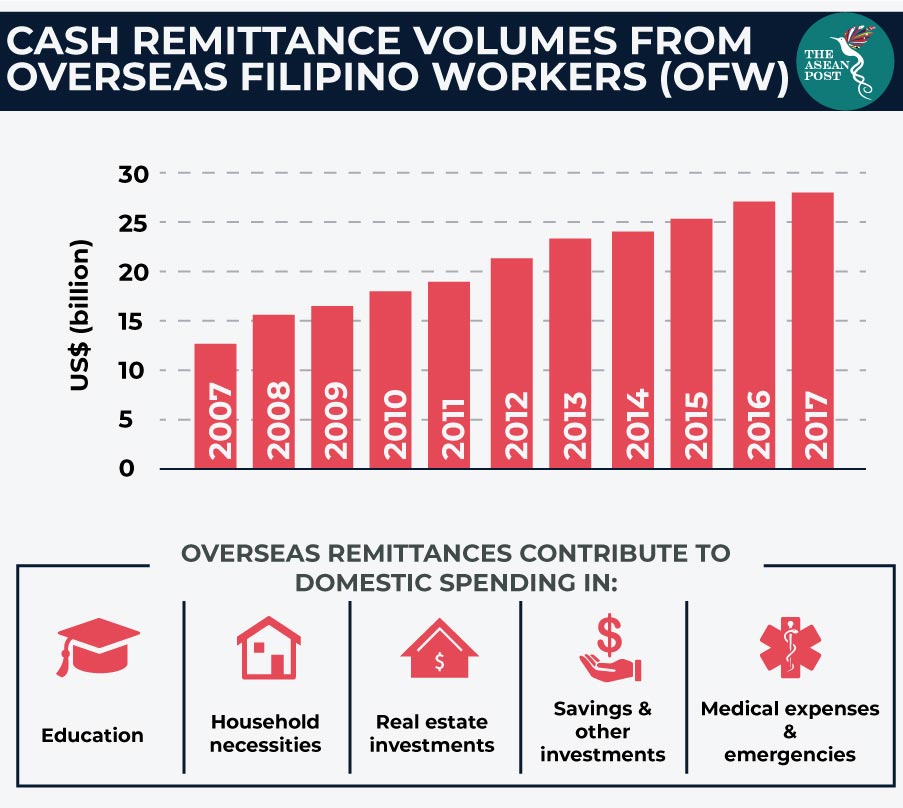

Data from the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP) released in February this year shows that cash remittances (remittances that flow through banks) from overseas Filipino workers (OFWs) grew 4.3% year-on-year, hitting US$28.1 billion in 2017. Out of this, remittances from the Middle East grew 3.4%.

According to I.F. Bagasao in his book chapter titled ‘Migration & Development: The Philippine Experience’, remittances received back in the Philippines are often put to a number of uses, including educating children, to pay for medical expenses, basic household necessities, to purchase homes or land, and to commit to savings or other investments.

In the chapter, which was part of the book 'Remittances: Development Impact & Future Prospects', Bagasao pointed out that such consumptive behaviour possesses a multiplier effect, particularly when used for education, health and housing, all of which contribute to economic development. A multiplier effect refers to how an increase in one economic activity can cause an increase in many other related economic activities, according to Investopedia. In fact, total remittances contributed towards 10% of the Philippines’ overall economic growth in 2017.

While the Philippines has a large number of workers employed overseas, higher remittances volumes could also be due to lower costs in remitting money through virtual currencies. Banks and agencies serve to facilitate the bulk of remittances, but the availability of bitcoin these days also reduces the cost of sending remittances back home. Remittances worth US$8.8 million in virtual currency were sent back to the Philippines every month during the first half of 2017, according to reporting by the Nikkei Asian Review.

Bloom Solutions is one example of a fintech start-up that has aimed to ease the process of remittance transfers. According to its website, the start-up aims to do so through the creation of a Bitcoin remittance platform and a domestic settlement network for remittance centres.

Concerns arose recently as to whether the imposition of a complete ban on new employment of OFWs in Kuwait could adversely affect steady remittance inflows. The Philippine government announced its intentions to repatriate 10,000 Filipino workers who have overstayed in Kuwait. The Philippines currently has 252,000 overseas Filipino workers employed in Kuwait, according to reporting by Reuters.

“I will sell my soul to the devil to look for money so that you can come home and live comfortably here,” Philippine president Rodrigo Duterte told CNN in February 2018.

President Duterte had imposed the ban in response to the death of several Filipino workers based in Kuwait, including the discovery of one Filipino domestic worker in a freezer located in a Kuwaiti flat recently.

Despite the ban imposition, analysts have commented that the total volume of remittances are unlikely to affect the Philippines much, given that its OFWs are usually spread across different countries.

“Filipinos always find a way to go somewhere,” Ruben Asuncion, chief economist of the Union Bank of Philippines told the Nikkei Asian Review in February. According to him, any potentially adverse impact on remittances would be merely temporal in nature.

“It should be highlighted that the sources of remittances from OFWs are quite well diversified, making remittances resilient to uncertainties in individual regions,” Aekapol Chongvilaivan, the country economist for the Philippines at the Asian Development Bank told The National in 2017. He was referring to a similar concern that arose when a 2016 economic upset Qatar triggered the possibility of Filipino workers being sent back home too.

A steady inflow of remittances is needed in order to balance the Philippines’ current account, which now stands at a deficit of US$100 million due to high infrastructure spending. The current account deficit is forecasted to grow to the size of US$700 million in 2018, according to estimates by the BSP. Meanwhile, the Philippines’ foreign reserves haven’t been rising, according to Reuters reporting in February 2018. Foreign reserves stood at US$81.57 billion as of December 2017, compared to US$83.83 billion in 2012.

Although the Philippines relies heavily on remittances to bolster its economy, it also needs to be able to balance this against adequate protection of its foreign workers overseas. A possible compromise would be to introduce foreign policy that regulates working conditions for OFWs abroad, as has been suggested by Kuwait’s deputy foreign minister Khalid al-Jarallah, recently. If that policy works to safeguard OFWs’ rights in Kuwait, the Philippines could consider similar policies for the rest of the countries where its OFWs currently reside.