Papua was formerly a Dutch-controlled colony and had since been annexed by Indonesia in 1963. However, strong separationist sentiments still prevail on the Indonesian half of the island and the freshly concluded elections there served as a catalyst for spates of violence similar to those which occurred in July last year.

Indonesian security forces often clash with armed Papuan rebels although President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo has arguably given more attention to the region compared to other presidents since the Soeharto administration. Nevertheless, according to a report by Jakarta-based Institute for Policy Analysis of Conflict (IPAC), Jokowi’s government has made several policy miscalculations there.

The first miscalculation is the belief that economic development would remedy any political grievances especially self-determination efforts. This is because development does not always translate to poverty alleviation. Hence, Papua remains the poorest province in the country. Besides that, in spite of other measures to lower prices of basic goods, empower Papuan women and increased access to education, the independence movement in the province has only grown stronger. This shows that higher levels of income and education do not necessarily translate to greater loyalty to the Indonesian state.

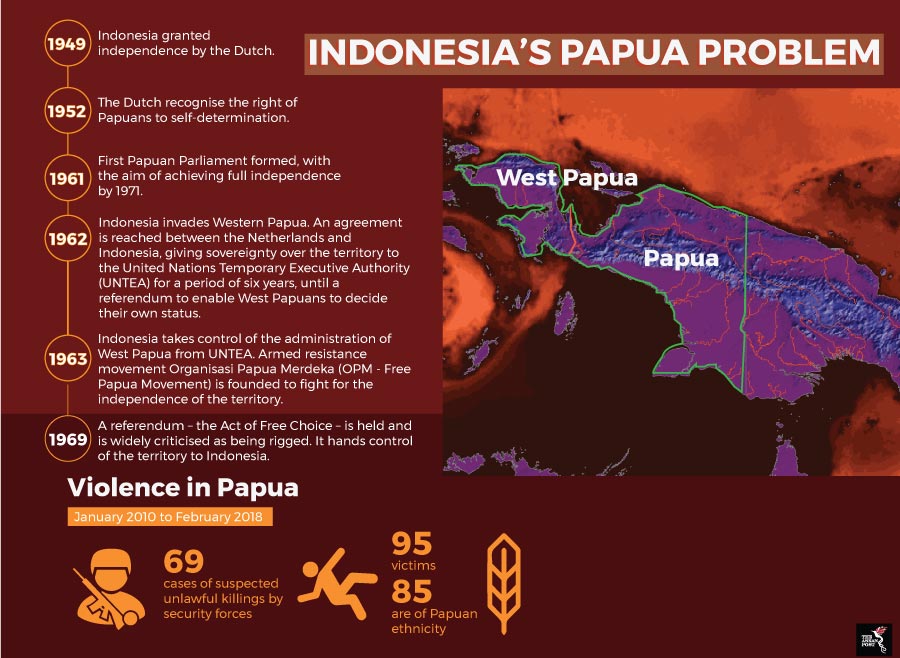

The second miscalculation is that outstanding human rights cases could be quickly resolved thus contributing to increased trust and goodwill on all sides. Violence in Papua has stemmed primarily from the extrajudicial actions of security forces who only receive a slap on the wrist from the government.

According to a report by Amnesty International, such unlawful killings have even taken place when security forces have had to deal with peaceful political protests, such as the Morning Star flag-raising ceremony – a symbol of Papuan independence – as well as religious gatherings. The report revealed that close to 100 people were unlawfully killed in a little more than eight years between January 2010 and February 2018.

In reference to several cases of extrajudicial killings, Usman Hamid, Amnesty International Indonesia’s Executive Director stated that it demonstrates the failure on the part of Indonesian security officers to distinguish between peaceful and armed protestors.

“The police and military must change their approach in dealing with peaceful political activities,” he said.

“The pattern of police and soldiers applying the same ruthless and deadly tactics they have used against armed groups to peaceful political activists is deeply worrying. All unlawful killings violate the right to life, a human right protected by international law and Indonesia’s constitution,” Hamid remarked, adding that “failure to investigate or bring those responsible to account reinforces the confidence of perpetrators that they are above the law, and fuels feelings of resentment and injustice in Papua.”

“Now is the time to change course – unlawful killings in Papua must end. This culture of impunity within the security forces must change, and those responsible for past deaths held to account.”

Will elections change Papua’s fate?

The final blemish on Jokowi’s policy towards Papua is the failure to reform the system of local elections there. The existing network of patronage and money politics have coloured local elections in Papua for a long time resulting in a repugnant spectacle of corruption that at times is tainted with violence which Jakarta has never attempted to prevent.

Indigenous-migrant tensions are a perennial point of contention. There have been calls for a requirement that only indigenous Papuans qualify to run as candidates for local elections. This issue also played out in the race for governor previously, where both candidates are indigenous. Lukas Enembe has always been a strong advocate of indigenous rights but his competitor, Jhon Wempi Wetipo had better support among the migrant community which could have played a crucial role in the final outcome in the event of a close election race.

Nonetheless, it was Enembe who came out victor with a whopping 67.5 percent of the vote. His strained relations with Jakarta is believed to have been a key factor to his continued popularity.

Over the years, he has built a strong political machine – even by means of political patronage – and enjoys the backing of many who are in support of pro-independence efforts. His re-election could spell further complications between Papua and Jakarta and the only way around it could be a compromise by both parties. But whether there is sufficient political will to achieve that, remains to be seen.

This article was first published by The ASEAN Post on 2 July 2018 and has been updated to reflect the latest data.

Related articles: