In the Philippines, it is just not drug-related criminals at risk of targeted murder, even journalists fall under the same threat. Based on a recent journalist death tally report by the International Press Institute (IPI), Philippines is the most dangerous country in Southeast Asia for journalists. 2017 alone has seen four confirmed journalists deliberately targeted under the rule of President Rodrigo Duterte.

The report noted that Latin America and the Caribbean were the “deadliest regions in 2017” for journalists whereas Mexico topped the list as the deadliest country for journalists with at least 14 killed.

Despite the implementation of mechanisms by the Mexican government to protect journalists in the country, they have been criticised as a failure. At least 80 journalists have been killed during “a wave of violence unleashed following then-President Felipe Calderon’s initiation of a war on the country’s drug cartels in late 2006” according to IPI.

Source: CPJ

Journalist killings in the Philippines

Back to the archipelagic nation of Philippines, 177 journalists and media workers have been killed since 1986. The Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) has deemed the nation as one of the most dangerous countries to practice journalism in.

The four journalists that were killed last year were Joaquin Brinoes, Rudy Alicaway, Leodoro Diaz and Christopher Iban Lozada.

According to a report by Inter Press Service, columnist Crisenciano Ibon also was shot by a gunman in the back, but survived, while his driver was wounded in August last year. The Philippine police speculated that the attack may have been in retaliation for his columns criticizing illegal gambling. Prior to that, he had also received many death threats for writing a critical piece on the illegal gambling situation in Batangas before he was attacked.

Broadcaster Rudy Alicaway and columnist Leodoro Diaz were attacked while riding their motorcycles. Unknown gunmen came up from behind and shot them dead. Their murders are likely linked to their reports on political corruption, underground gambling and the drug trade. Journalist Joaquin Briones - who was known for his hard-hitting radio program at the local dyME radio station - was killed in a similar way.

There was also a fifth killing, although not included in the official statistics of the International Federation of Journalists (IFJ). In August 2017, Michael Marasigan, a respected former newspaper editor, was shot dead in Manila. Until today, no arrests have been made in connection with this murder despite Duterte’s administration’s statement of doing all it can to detain whoever is responsible for the killing.

Human Rights Watch (HRW) has called for state action with regards to these brutal journalist killings. Previous administrations launched similar task forces on media killings, but they have all failed. “Despite its assurances that journalists are ‘safer’ now, Duterte’s task force will suffer the same fate so long as the administration actively endorses extrajudicial killings. Without accountability for killings of journalists, media freedom in the Philippines will remain under threat,” stated Carlos H. Conde, a researcher from HRW.

Waning press freedom

In its World Press Freedom Index released in April 2017, Reporters Without Borders (RSF) also identified the Philippines as one of the most dangerous countries for the media, currently ranking 127th out of 180 countries.

Apart from journalist killings, the revoking of the license of independent media outlet, Rappler by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) is also seen as another major blow for Philippines’ press freedom.

Rappler, one of the most prominent independent news outlets in the Philippines, has aggressively investigated the administration of President Rodrigo Duterte for his violent, police-led campaign against drug users. Rappler has been called “fake news” by the Philippine president and is now facing government action that could force its closure.

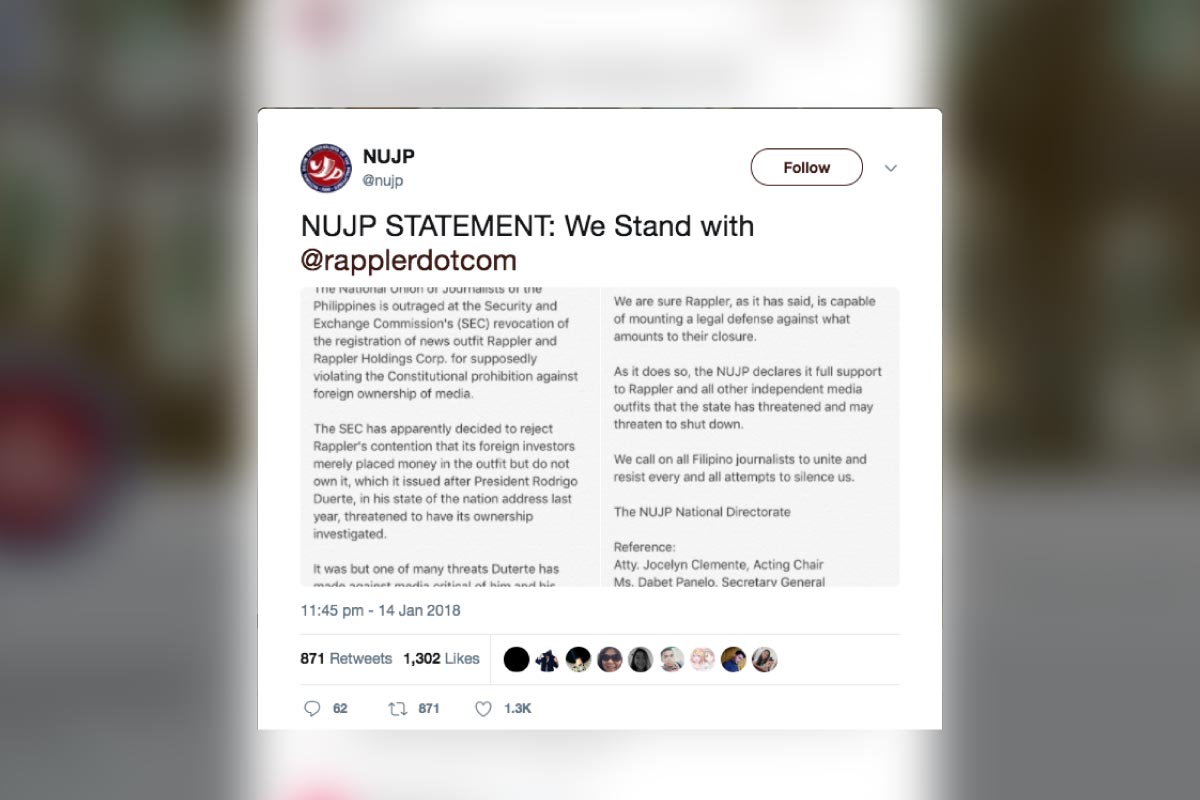

The National Union of Journalists of the Philippines (NUJP) has also spoken out and called for “…all Filipino journalists to unite and resist” attempts by the government to silence the media.

With the growing number of press outlets and reporters facing severe consequences in the region for reporting on controversial issues, it is indeed a worrying trend that threatens declining media rights and freedoms in Southeast Asia.

Related articles