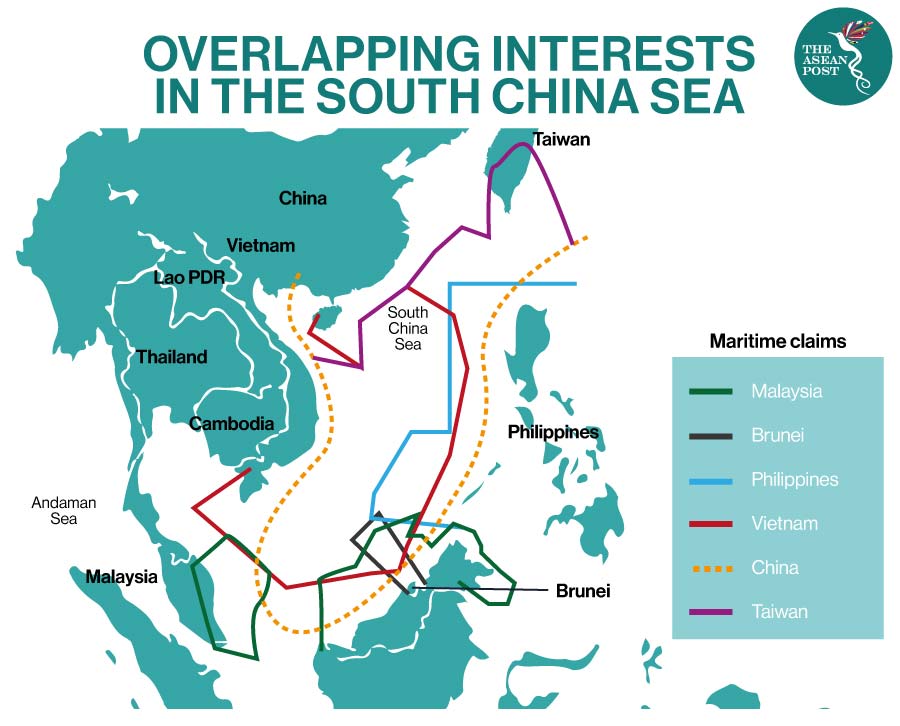

The South China Sea (SCS) dispute is one of the many inter-state issues that challenge the resolve of the Philippines’ foreign policy of upholding peaceful coexistence and mutual respect with other claimant-states, especially China.

This is in line with a peaceful and diplomatic resolution of the dispute based on the Philippines’ commitment to international law, regional stability, and peaceful co-existence with its neighbours, without compromising the integrity of its national territory, sovereignty, national interests, and security.

Such resolve was challenged during the Scarborough Standoff in 2012 under the watch of President Benigno Aquino’s administration.

The Scarborough Shoal Standoff in 2012 pertains to the tensions between China and the Philippines over the disputed Scarborough Shoal. Tensions began on 8 April, 2012, after the attempted apprehension of eight Chinese fishing vessels near the shoal by the Philippine Navy.

The more than two months standoff at the shoal ended when the Philippines pulled out on 15 June, 2012. The direct consequence of the standoff and subsequent pull-out of the Philippine Navy resulted in a shift in control of the shoal from the Philippines to China, which has constantly maintained a coast guard presence at the shoal since 2012.

The Scarborough Shoal is a rock in the South China Sea, approximately 120 nautical miles west of the Philippine island of Luzon which is claimed by the Philippines and China. There are no structures built on Scarborough Shoal thus far.

PCA Ruling

To save face because of the poor handling of the Scarborough Standoff, the Aquino administration opted for a legal approach instead of conceding to the insistence of China to resolve the conflict of interest over the Scarborough Shoal through bilateral negotiations and dialogue without the involvement of the United States (US) or other powers not party to the dispute.

In 2013, the Aquino administration filed a case against China at the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) in The Hague, Netherlands which resulted in a promising outcome in favour of the Philippines. However, China made it clear from the very beginning that it would neither accept nor participate in the arbitral proceedings because as far as it was concerned, the contentions presented by the Philippines were not within the jurisdiction of the Tribunal.

China made a declaration on 25 August, 2006 stating that it does not accept any of the procedures provided for in Section 2 of Part XV of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) concerning all the categories of disputes referred to in Paragraph1(a)-(c) of Article 298 of the Convention. The Philippines also submitted a similar “understanding”.

Elucidations

Nevertheless, the tribunal award gave the Philippines a moral high ground and resulted in some kind of euphoria among Filipinos in general. Moreover, as a proviso, the PCA ruling did not denote the victory of sovereignty (ownership) over the territorial and maritime claims of the Philippines in the disputed waters of the SCS.

This means that the arbitral tribunal did not tackle matters related to territorial sovereignty over the disputed maritime features between the parties, which further means that the tribunal did not decide who owned the maritime features located in the SCS, such as the Spratly Islands, that are claimed by China and the Philippines and even Vietnam and Malaysia as well.

Similarly, the tribunal did not delimit (demarcate or set limits) of any maritime boundaries between the Philippines and China in the SCS.

The award simply clarified the maritime entitlements of the Philippines in the West Philippine Sea (WPS), declared the nine-dash line of China as being without basis, acknowledging the damage to the marine ecosystem and resources caused by reclamations in the SCS, and even ruled that the surrounding waters of the Scarborough Shoal as a traditional fishing ground where Filipinos, Chinese, and even Vietnamese can fish. It also stated that the shoal is a rock that cannot generate an Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) because it cannot sustain life.

Another factual inaccuracy that needs to be clarified for Filipinos to have a deeper understanding of the so-called arbitral ruling is the fact the award is not a PCA ruling. Although, the PCA discharged and announced the ruling, nonetheless, the PCA only served as the registry (record office) or secretariat (a permanent administrative office that carries out substantive and administrative work) of the arbitral tribunal constituted under the UNCLOS.

Tetsuo Kotani in his article, “The South China Sea Arbitration: No, It’s Not a PCA Ruling,” explained that the PCA is not a court in the general sense but an administrative body with the object of having permanent and readily available means for arbitration.

The PCA serves as the registry, rather than a tribunal, and facilitates arbitration and other dispute resolution proceedings among states, intergovernmental organisations, and private parties. Kotani also further clarified that unlike the International Criminal Court (ICJ), the PCA is not a UN organisation.

Realities

One of the many issues and dilemmas behind the PCA ruling is the issue of enforcement. In an anarchic international state system, where the world lacks any supreme authority or sovereign, meaning there is no world police force, the PCA ruling can be likened to a paper tiger which appears to be powerful or threatening, but is in fact ineffectual. Thus, it is somehow challenging and difficult to enforce. This is the glaring reality.

Even if the PCA ruling had the backing of a UN General Assembly resolution, it would never have the guarantee of enforcement through UN mechanisms. Consisting of 193 members where one country has one vote; apart from the approval of budgetary measures, UN General Assembly (UNGA) decisions in the form of resolutions are at best a “recommendation”.

This means they have no binding power over member states. And in any case, if the tribunal award is then brought to the UN Security Council (UNSC) on the pretext of “peace and security,” it will also be shot down as China is a permanent member of the UNSC.

To note, decision-making at the UNSC is by consensus and permanent members like China can veto any resolution that goes against its sovereign interests.

Take the case of Nicaragua vs. the US in 1986. The International Court of Justice (ICJ) ruled that the US had violated international law by supporting the Contras in their rebellion against the Sandinistas and by mining Nicaragua’s harbours.

The case was decided in favour of Nicaragua and against the US with the awarding of reparations to Nicaragua.

However, the US refused to participate in the proceedings, arguing that the ICJ lacked jurisdiction to hear the case. The US walked out of the Court after the jurisdictional decision was rendered but before the merits phase got underway. The US also blocked enforcement of the judgment through the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) by exercising its veto power and preventing Nicaragua from obtaining any compensation.

The UNGA adopted four resolutions calling for “full and immediate compliance with the judgment of the ICJ, but the US, however, continued to claim that the ICJ did not have jurisdiction in the case and had exercised its veto in the UNSC. Hence, Nicaragua did not succeed in securing full US compliance with the judgment.

The only way to enforce the PCA ruling without the concession of China, if the Philippines insist, is to go to war. Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte begs the question at what cost and at whose expense, and who would ultimately benefit from it?

For Duterte, war is not an option in resolving its dispute and differences with China because no one would benefit from it. In a war, everyone loses in some way or another. That’s a fact of life which has been witnessed throughout the history of the world.

Another reality that Filipinos must contend with is the uneven balance of power, the blatant asymmetry of economic and military power between the Philippines and China, soft power projections and the increasing influence of China on the international stage among countries.

One should take note that China’s soft power projections and influence in the world have gained so much traction especially in this time of the coronavirus pandemic. This is because China has been helping the developing world by supplying necessary vaccines and other forms of assistance in combating the COVID-19 pandemic.

Another factor is the launch and continuous traction achieved by the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), and now the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) – a free trade agreement between the Asia-Pacific nations of Australia, Brunei, Cambodia, China, Indonesia, Japan, Lao, Malaysia, Myanmar, New Zealand, the Philippines, Singapore, South Korea, Thailand, and Vietnam.

Thus, when it comes to persuasion and influence between the Philippines and China, it is obvious that China will win to its side many developing world countries, least developed countries, and countries that are part of the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM), which is a large voting bloc as well in the UNGA.

This is precisely because these countries have economic and trade partnerships and development projects with China and won’t want to sacrifice or jeopardise them for the sake of the Philippines over the PCA ruling.

The rationale of any state is to always prioritise its interests over the interests of other states to survive in the anarchic world order. This is the hard reality that Filipinos must come to terms with because this is realpolitik in inter-state relations.

Hence, the Philippines must navigate through these realities prudently and judiciously to protect itself and preserve its national interests and security. It is prudent and wise to choose the path of diplomacy rather than conflict when resolving the country’s differences with China via constructive bilateral relations coupled with multilateralism within the ambit of both, international laws and ASEAN, by pushing for the China-ASEAN Code of Conduct (COC) for the SCS.

Moving Forward

The Philippines and China are friendly neighbours and this will probably never change through time. And even among friends, conflicts of interest and differences exist. But what matters is the maturity and constructive way of resolving these differences.

Thus, rather than singling out, demonising, and ostracising China, which may result in further escalation of conflict between the two countries, the Philippines should rather prioritise pushing for the conclusion of the COC, establish strategic partnership with China, and collaborate on practical solutions to the SCS dispute which may include joint exploration and development of fishing, oil, and gas resources in the SCS, coupled with continued shared infrastructure and coordinated investments.

This win-win strategy and solution are akin to turning a dilemma into an opportunity that engenders tangible benefits and fosters a better and progressive future for all Filipinos and Chinese, rather than the “zero-sum game” of singling-out, targeting, and isolating China.

At the end of the day, establishing amity and mutual understanding between the two countries is key to sound state-to-state relations.

This Is Part 2 Of A Series Of Articles On The South China Sea Dispute

Related Articles: