Cambodia has emerged as one of Southeast Asia’s most promising young markets in recent years, with its construction and garments industries in particular attracting the lion’s share of foreign direct investment (FDI) to the nation, which amounted to US$1.92 billion in 2016.

Part of the appeal to regional and Chinese investors, who have wasted no time in relocating manufacturing bases to or launching new ones in the Southeast Asian kingdom, is Cambodia’s young population, more than half whom are between 15 and 50 years of age, and as such constitute an ideal labour force for manufacturing operations.

However, as the country’s economy gains momentum following its transition to an open market system in 1995 and concerted efforts to integrate itself into ASEAN and global trade, this generation of Cambodians – survivors of the brutal Khmer Rouge regime or their children – are being left behind as breakneck development outpaces sustainable housing growth.

Boreys as a business

Phnom Penh is Cambodia’s capital and most populous city by far, with 1.4 million residents, or 2.2 million if its larger metropolitan area is taken into account – 11 times greater than the next largest city, Battambang, with a population of 200,000. Rural-urban migration is a driving factor, as income disparity forces the rural poor to seek opportunities in the city.

Unfortunately, the influx of foreign developers such as Singapore’s Oxley Holdings Ltd and China’s Prince Real Estate Group has fuelled an ever-growing emphasis on luxury residences far out of reach of local home seekers. This scenario is not unique to Cambodia, with Chinese developer Country Garden’s venture into Malaysia contributing to rampant oversupply in the high-rise luxury segment in the southern state of Johor.

In Phnom Penh, such market distortion comes in the form of a preference among developers for boreys – gated communities comprising single, twin and hybrid villas, linked homes, shophouses and more, along with amenities such as gardens, markets, retail stores and other conveniences.

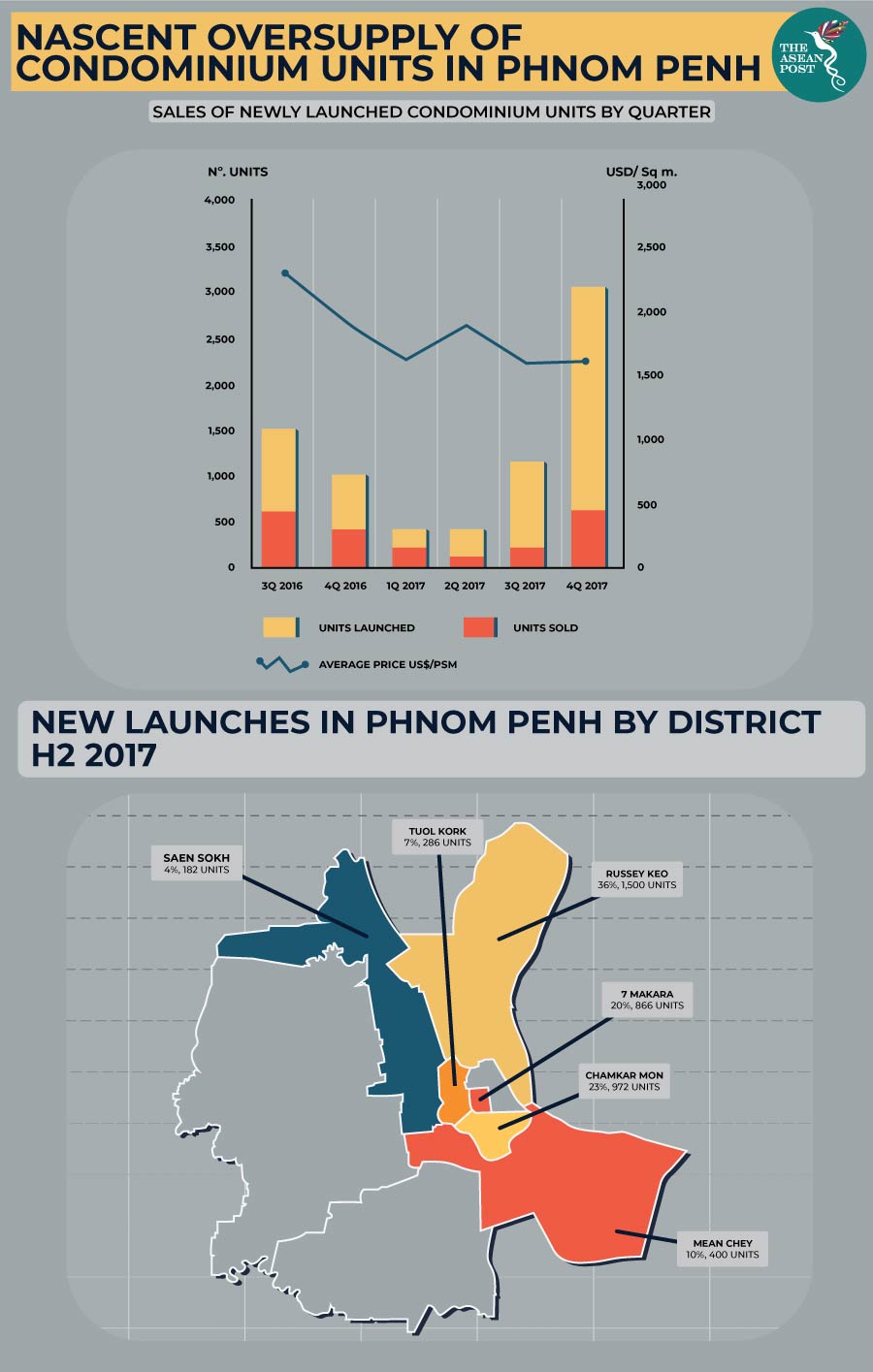

Luxury serviced residences and condominiums are also a common sight, with construction cranes, half-built towers and work sites swathed in protective green cladding a staple of the Phnom Penh skyline today. The total supply of serviced apartment units in the capital came to 4,905 units, along with 7,413 condominium units, according to Knight Frank Cambodia in its Real Estate Highlights 2nd Half 2017 report.

But who is buying these luxury residences? “In terms of purchasing, it’s basically all Chinese. Most people are buying for investment, though some will live in their flat because they have a company or do business here,” said Chen Jingjing, a sales agent at a major Prince Real Estate project in Phnom Penh.

Shift in housing agenda

The specialised target markets for these products is a function of their pricing. Units in Borey Peng Huoth and Borey Piphup Thmey, for example, start at US$60,000, while previous high-rise projects focused on even higher price points up to US$80,000, according to Cambodia Properties Ltd chairman Cheng Keng.

This is in stark contrast to the minimum wage for garment and footwear workers of US$153 a month, set by Cambodia’s Labour Advisory Council on 1 January 2017, and an annual household income per capita of US$1,093 in 2015, according to Singapore-based economic research firm CEIC. As of 2017, the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) estimated that 13.5 percent of the Cambodian population still subsisted below the poverty line.

The plight of Cambodian home seekers has seen the involvement of non-governmental organisations such as Habitat for Humanity, which estimated in its 2017 Building Tomorrow report that up to 9.8 million Cambodians today lack access to decent housing, including 8.8 million without access to adapted housing micro loans, and 2.8 million who live in slums.

Thanks in part to advocacy on Habitat for Humanity’s part, the Cambodian government has launched a number of initiatives to address the glaring lack of affordable housing measures in Phnom Penh’s property landscape, including the construction of 55,000 homes priced below US$30,000 yearly towards the eventual target of 800,000 units by 2030 to meet population projections.

However, progress on this front has been slow, with only 10,000 affordable units from private developers forthcoming to date. In addition, only three affordable housing projects have received government approval entitling them to tax incentives and state support, discouraging active developer participation until clear guidelines are established with regard to affordable pricing, tax breaks and regulatory frameworks.

Fortunately, regional investors have taken the lead in driving the national housing agenda forward, working hand in hand with domestic players. Babylon Real Estate Development is an example of such a collaboration, representing a 51:49 joint venture between Sy Bunthay, an established Cambodian entrepreneur and the Kuala Lumpur-based investment platform Owners Circle.

“With Cambodia’s rapid globalisation, there are a large number of labourers migrating from provincial or rural areas to the capital. Investment from foreign countries into the upper market segment is also very strong, resulting in a mismatch in housing supply and demand which has increased segregation, leading to problems in terms of urban development,” explained Babylon Real Estate Development chief financial officer Vincent Loh.

“There are also many countries such as Malaysia, South Korea and particularly China, which are allocating resources into Cambodia. We believe the Phnom Penh housing market will see hypergrowth as a result. However, foreign investors tend to be more focused on profitability and prestigious real estate developments, which are often based upon speculation. As a result, this will push land values up, and drive cheap rental housing further and further away from the city.”

Established to address development gaps in Cambodia while fulfilling the needs of its people, Babylon Real Estate Development focuses on building affordable, quality homes to elevate lifestyles in Phnom Penh and beyond.

Other initiatives include partnerships between the UNDP and the Phnom Penh Special Economic Zone (PPSEZ), one of a number of designated areas within Cambodia with business and trade regulations conducive to FDI. The partnership offers cash prizes up to US$20,000 for designs for a 3,000-unit housing project in the PPSEZ, which has seen an influx of low-income workers in need of affordable homes.

As Cambodia leverages on its status as one of ASEAN’s most vibrant emerging markets, parlaying regional goodwill and cross-border business opportunities into an engine of growth for its people, its government must ensure that its citizens are able to enjoy the fruits of their labour. Without homes, rapid urban development and economic expansion will leave this generation of dispossessed Cambodians on the outside, looking in.