ASEAN (Association of Southeast Asia Nations) recently celebrated its 50th anniversary in August and has come a long way since its commencement through the 1967 Bangkok Declaration. The organisation promotes economic cooperation, political stability, good governance and civil liberties – which were the founding principles on which the association has been built upon. In terms of trade and economic prosperity, the ASEAN community has shown astronomical growth over the last five decades and is now emerging as the seventh largest economy in the world. Sadly, civil liberty and human rights issues – in reference to the freedom of expression and freedom of press – have not progressed in tandem with the region’s economic wealth. They remain very much limited and are heavily controlled by the respective governments in countries within the ASEAN bloc.

The lack of press freedom in ASEAN countries continues to be a growing concern – especially with the recent press crackdown in Cambodia.

The diminishing press freedom

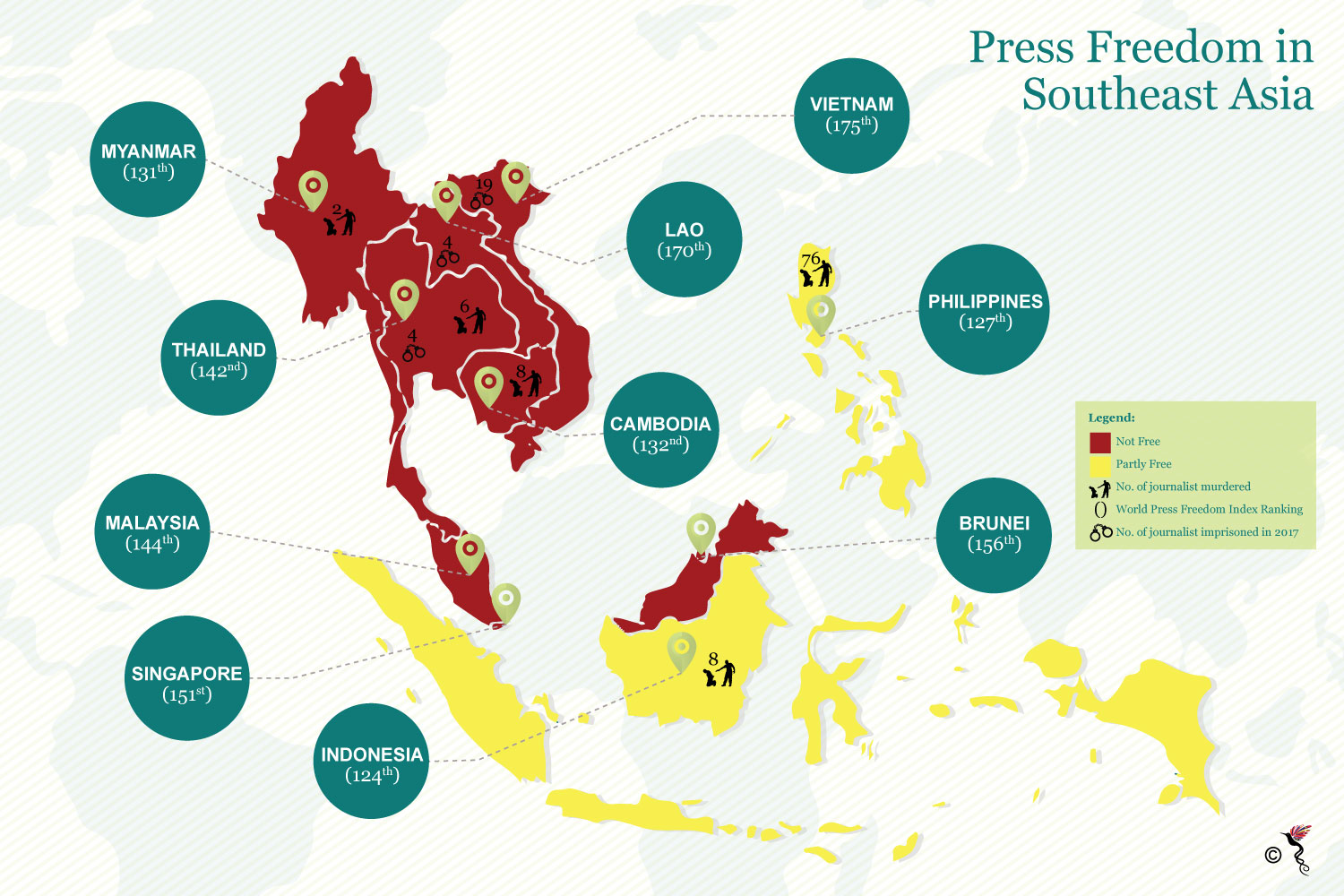

According to the human rights watchdog organisation, Freedom House, ASEAN nations are either “not free” or “partly free” in terms of press freedom, which is heavily repressed by the authorities. The ASEAN governments are becoming stricter, resulting in a shrinking civic space for an individual, organisation or news media outlet to voice out their opinions, especially those that are critical of the authorities. Due to the cultural and political differences within the ASEAN region, the challenges facing press freedom vary from one country to another, as highlighted by the RSF (Reporters Without Borders).

Indonesia: The administration of Indonesian president Joko Widodo continues to violate press freedom, including limiting media access to Western New Guinea, where the military and radical religious groups carry out acts of violence and intimidation against local journalists. As the situation has become increasingly intolerable, journalists in Indonesia practice self-censorship to avoid from being a victim of such harassment.

Philippines: Filipino president Rodrigo Duterte continues to criticise the press – citing that the media is propagating false news about him. The Philippines continues to be one of the most dangerous countries for journalists as private militias are often hired by local politicians to silent opposing voices with complete liberty.

Myanmar: The country's authorities continue to exert pressure onto the media and has even intervened directly to alter editorial policies. Therefore, journalists in Myanmar continue to practice self-censorship in connection to matters relating to government officials and military officers because they fear arrest or imprisonment for criticising the authorities.

Cambodia: Media outlets in Cambodia are closely monitored and Hun Sen's government maintains a good rapport with owners of leading media organisations. The Cambodian government has become more hostile towards independent media outlets, especially after the murder of a famous political commentator and activist Kem Ley in 2016. Over the last decade, many journalists in Cambodia have been murdered for covering sensitive issues related to the local government's administration.

Thailand: Numerous laws have been enacted by the Thai government to ensure public circulation of news will not affect the reputation of the monarchy, military junta and leaders like the Thai prime minister Prayuth Chan-o-cha. Monitoring bodies like the Military Media Monitoring Unit and Police Media Monitoring Unit with the assistance from Cyber Scout, have placed journalists in Thailand under permanent surveillances, who are often summoned for questioning or detained arbitrarily.

The press freedom of Southeast Asia, as compiled from Reporters Without Borders (2017 World Press Freedom Index), Committee to Protect Journalists and Freedom House.

Malaysia: Although more progressive and matured than its ASEAN counterparts, Malaysia still restricts press freedom through laws and regulations. Journalists and the civil society are not allowed to freely express their thoughts as it perceived to be detrimental to the nation’s peace and harmony. In addition to that, the printing presses in the country are subjected to the PPPA (Printing Presses and Publications Act 1984) which requires them to apply for a licence granted by the Home Affairs Minister that needs to be renewed every year. The minister could also choose to revoke or suspend the permit, thus putting immense pressure onto the printing presses.

Singapore: The Singaporean government does not respond well to criticism from journalists and it is known for taking legal actions, applying pressure to render them jobless or even to force them out of the country. A defamation and sedition lawsuit can result up to 21 years in prison upon conviction. Apart from that, the Media Development Authority has the power to censor journalistic content, both in the traditional and online media.

Brunei: Brunei's repressive legislation does not tolerate any blasphemy or criticism of the Sultanate. Journalists in Brunei practice self-censorship when reporting on topics relating to politics and religion.

Lao: The Laotian government practices absolute control over the press. Any journalists found criticising the government will be imprisoned. There is also a lack of media pluralism in Lao because only three out of 40 local TV channels are privately-owned. Any foreign media in Lao must submit their content to the government for censorship before publishing or broadcasting it.

Vietnam: The media is fully controlled by the government and independently-reported information by bloggers or citizen journalists are subjected to harsh persecution. To justify themselves, the Government resorts to Articles 88, 79 and 258 of the Criminal code, under which “anti-state propaganda,” “activities aimed at overthrowing the government” and “abusing the rights to freedom and democracy to threaten the interests of the state” respectively are punishable with imprisonment.

ASEAN must work towards greater press freedom

According to the ASEAN’s Human Rights Declaration, “every person has the right to freedom of opinion an expression, including freedom to hold opinions without interference and to seek, receive and impart information, whether orally, in writing or through any other medium of that person’s choice.” This should not only be words on the paper of the ASEAN Charter 2025, but press freedom must be widely practised in all ASEAN countries, emulating countries that offer total freedom to the press.

According to the Executive Director of SEAPA (Southeast Asian Press Alliance) Edgardo Legaspi during his speech at World Press Freedom Day 2017 forum held in Jakarta of Indonesia, “the press has an important role in regards to freedom of expression, especially if there’s problem, the press is able to ask the officials for clarification and so could be conveyed to the people. The responsibility of a journalist lies in promoting freedom of expression to the public, for the public and in behalf of the public.”

SEAPA is a non-profit, non-governmental organisation campaigning for genuine press freedom in Southeast Asia. Established in Bangkok in November 1998, it aims to provide a forum for the defence of press freedom, giving protection to journalists and nurturing an environment where free expression, transparency, pluralism and a responsible media culture can flourish.

Legaspi agrees that the safety of journalists and the freedom of the press in ASEAN is not without any challenges as ASEAN nations do not fully practise the freedom of expression. However, he assured that SEAPA still believes in ASEAN and has not given up on it as yet. He recognises that a lot of work still needs to be done in terms of press freedom and urged the ASEAN community to come together to plan for concrete steps in making press freedom a reality within the region.

“Freedom of expression is an important issue in ASEAN because freedom of expression means that the government can count on the people to discuss development and people are able to get information from the government to be able to decide their development,” Legaspi added. This is a two-way communication that will help in ASEAN’s development. The media must be able to decide independently what they want to write about or publish – and must be free from any government interventions or threats.

The ASEAN leadership should also start by reforming the current socio-political culture by providing 625 million of its citizens more freedom and space for expression, enhancing civil liberties and improving human rights conditions – in areas of freedom of expression and press freedom. Governments in the region must be open to greater press freedom and accountability. Freedom of expression should be a basic right of any human being, and without it true democracy and accountability are impossible to achieve.