Leaders of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) will head to the island republic of Singapore at the end of this month for the 32nd ASEAN Summit and a sempiternal item on the agenda is economic integration. The term is often thrown about without much thought at such meetings but by its very nature, integrating 10 economies of varying shapes and sizes is a monumental task. Besides that, the “ASEAN Way” of conducting negotiations often times makes progress on the matter exasperatingly transient.

However, credit should be given where credit is due. The economic domain was not initially part of ASEAN’s main focus. Through the Cold War era, ASEAN was primarily a bloc intended to stem the red scare from spreading on this side of the world. With the fall of the Berlin Wall, many had cast the association to the doldrums of history but ASEAN was nimble enough to adapt and shifted its focus to uplifting and promoting the regional economy as a whole.

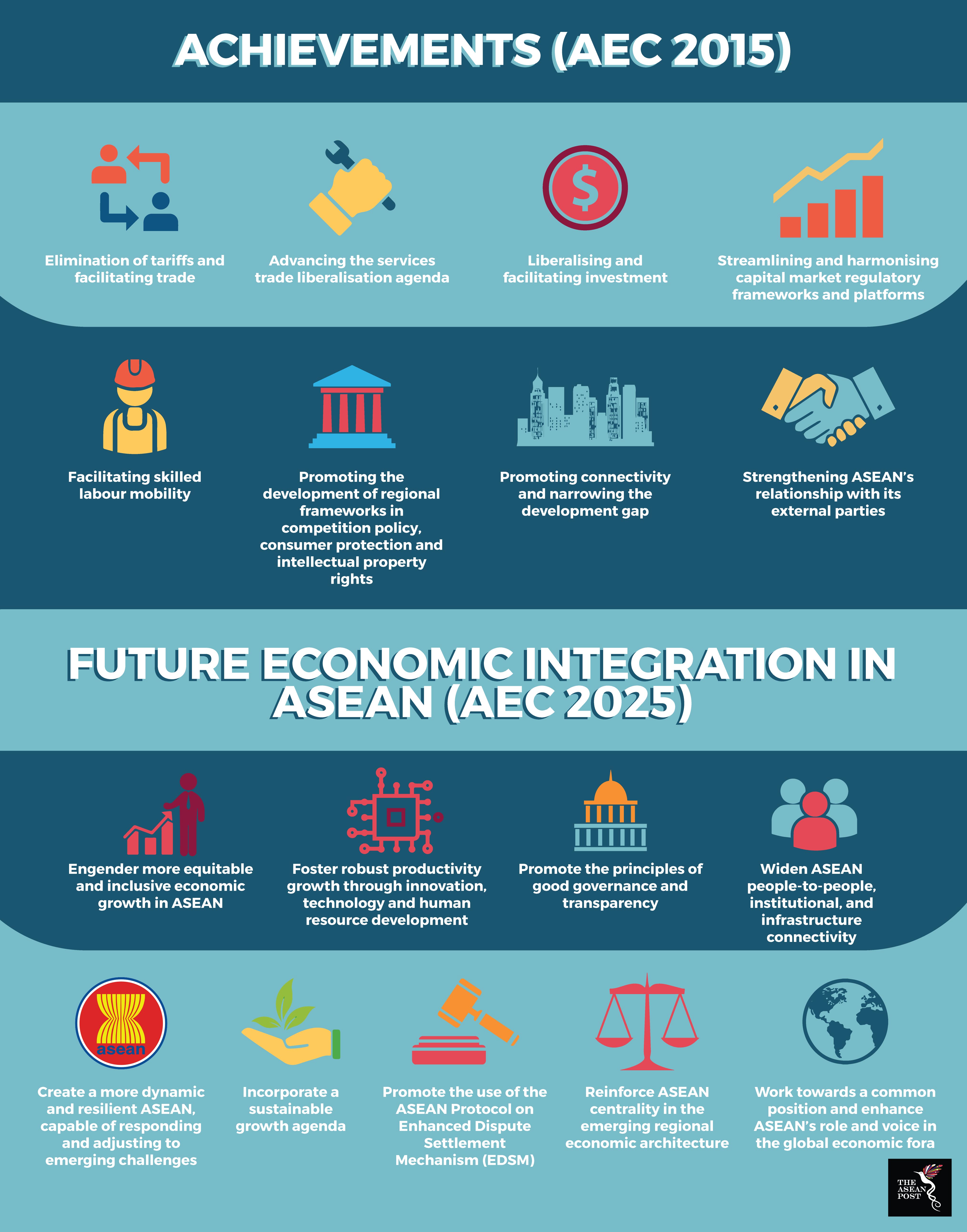

After staving off the Asian Financial Crisis in 1997, 10 years later, leaders of the 10-member association agreed to the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) Blueprint which was to be realised between 2007 and 2015. It aimed to transform ASEAN into a single market and production base, a highly competitive economic region, a region of equitable economic development, and a region fully integrated into the global economy. ASEAN had truly set its sights on a global ambition whilst being staunchly regional.

Singapore’s chairmanship of ASEAN this year, under the tagline “Resilient and Innovative” presents a unique stepping stone for the 10-member bloc to explore possibilities in the digital economy. Given Singapore’s prevailing successful ventures into the digital space, Singapore’s leadership in this foray would be greatly beneficial to the other member state economies.

Singapore already has plans to develop a regional network of smart cities and since many other member states like Malaysia, Thailand and Vietnam have been looking to develop smart cities of their own, who else better to help in that endeavour than Singapore. The island nation is one of the most technologically advanced in the world with relevant policy frameworks tried and tested.

Moreover, the ASEAN digital economy will potentially be valued at US$200 billion by 2025 with e-commerce accounting for US$88 billion. A large chunk of the latter would likely come from Chinese e-commerce giants, Tencent and Alibaba which have made large key investments in startups based in the region.

China’s plans with Southeast Asia doesn’t end there. The ASEAN region which is home to over 630 million is a prized market for Beijing which is looking to deepen economic ties with member states. Southeast Asia is also a key part of the grandiose Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) which connects almost a third of the planet. The plans include infrastructure investments worth billions of dollars that would help fund railway tracks, roads, ports and power plants along the belt.

Most of the world is wary of China’s intentions with a plan of such scale, and quite rightly, ASEAN should too. However, ASEAN’s strength lies in its numbers. Furthermore, with Singapore being the leader this time around, it helps the regional association in two ways. Firstly, Singapore has a reputable diplomatic track record with China making it a perfect “representative” of this region. And secondly, Singapore is not involved in maritime disputes with Beijing which means it can be depended upon to be a mediator between ASEAN and China because economic ties are also dependent on prevailing political conditions.

The AEC is very much a work in progress and according to former ASEAN Secretary General, Ong Keng Yong, will very much remain the same even after 2025, when the next phase of the AEC – 2015 to 2025 – reaches its conclusion. ASEAN’s economies are chugging along at different speeds, hence to attain the objectives of the AEC will take longer than expected. With Singapore leading the bloc this year, we can anticipate positive progress which would only further propel the regional economy.