All over the world, democracy is in retreat. In 2020, the Democracy Index, published by the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) since 2006, fell to its lowest-ever global level. This development cannot be attributed exclusively to restrictions imposed due to the pandemic, because the ratings have been in free fall since 2015.

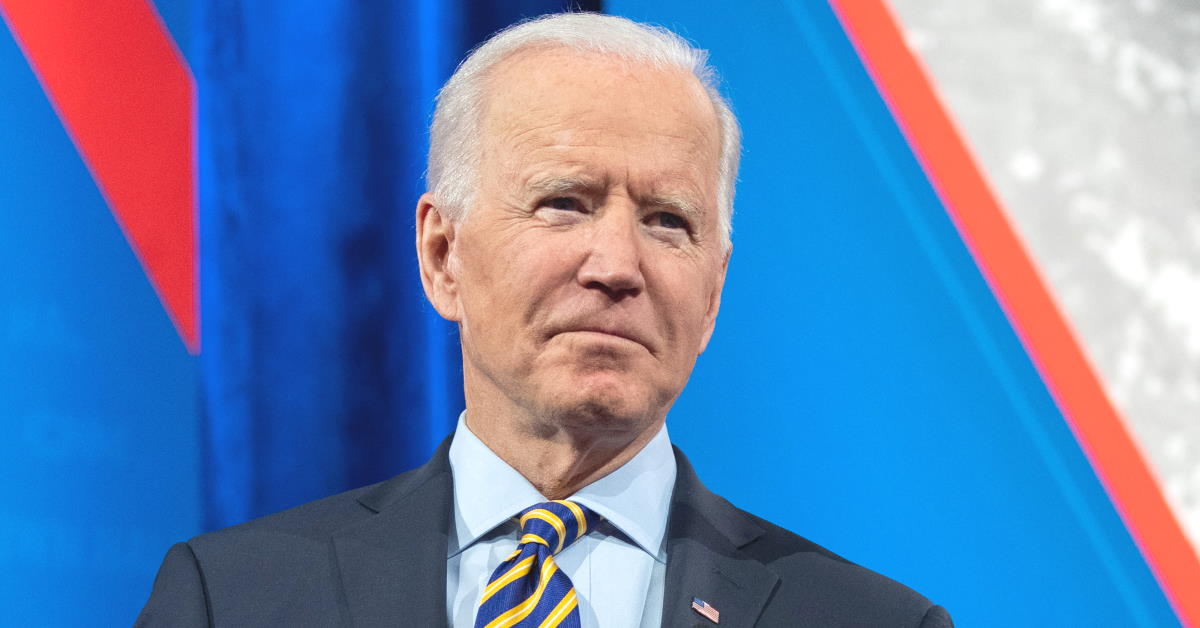

So, it is not surprising that in his first foreign policy speech as United States (US) president, Joe Biden focused on the need to safeguard democratic values around the world. Biden reaffirmed his intent, which he announced during his campaign, to organise a Summit for Democracy early in his presidency.

In Biden’s own words, this summit “will bring together the world’s democracies to strengthen our democratic institutions, honestly confront countries that are backsliding, and forge a common agenda.” The United Kingdom (UK) has embraced the idea by proposing the establishment of a D10, to be formed with the members of the G7 along with Australia, India, and South Korea.

The outline and complementarity of these proposals have not yet been determined, but their essence is far from new. When John McCain ran for president against Barack Obama in 2008, he advocated the creation of a League of Democracies that would encompass more than a hundred states.

In fact, when McCain floated the idea, a similar (but more modest) coalition had already existed since 2000, when the US and Poland spearheaded the foundation of the Community of Democracies (CoD). That initiative still operates, but it is almost completely forgotten, demonstrating the difficulty of sustaining such efforts.

From its beginning, the CoD was hampered by incongruities and tactical dissention, as well as by doubts about its purpose. Unfortunately, the countries that joined the project were not successfully encouraged to perfect their respective democratic systems.

One revealing fact is that the organization’s seat is in Poland, currently at number 50 in the EIU rankings, after marked democratic deterioration in recent years.

Before getting underway, Biden’s Summit for Democracy will face the very questions that caused similar projects to run aground: who, how, and why. When considering these questions frankly, one can identify a series of obstacles and drawbacks, which lately have become even more difficult to circumvent.

The first uncomfortable reality that the US must negotiate is that, even though it maintains much of its gravitational pull in the international arena, its reputation as a standard-bearer for democracy has suffered some significant blows. Clearly, the country is passing through a serious institutional and social crisis, owing largely to the transgressions of the Trump administration, with the connivance of the Republican Party.

Biden’s arrival – with his promise of unity and eagerness to mend fences – has been a great relief, but his conciliatory approach will not bear fruit overnight. Beyond these domestic considerations in the US, which other countries would be invited to the summit? Inviting too many would make reaching consensus more difficult, while including too few would lead to unproductive overlaps with existing forums such as the G7.

Moreover, inviting some governments with dubious democratic credentials could contribute to whitewashing their practices, but excluding them could lead to diplomatic crises and be counterproductive from a strategic point of view.

It remains to be seen whether Biden contemplates merely a single summit or a more permanent coalition – perhaps even taking an institutionalised form. The first option would be purely symbolic and hardly worth the effort. The second would run up against the imperatives of a multipolar order in which economic ties and vicinity play an essential role.

Sharing the same political system does not imply sharing the same interests and priorities, so providing a coalition of democracies with a concrete, substantial, and lasting objective is practically impossible. When realpolitik enters the scene (for example, in trade matters), the coalition could be discredited.

Lastly, although a Summit for Democracy could be packaged positively, not punitively, it would surely be interpreted as an effort to draw a sharp dividing line between democracies and autocracies. To situate this dividing line at the centre of international relations is to risk precipitating what we can still avoid: another cold war, this time between the US and China.

In the face of the tremendous global threats looming over us, from pandemics to climate change, a dynamic of confrontation between rival blocs would impede – if not prevent – the multilateral cooperation that we sorely need. But recognising the drawbacks of Biden’s proposal does not mean that we should resign ourselves to the global decline of democracy.

Although it is advisable to opt for the G20 or for even more representative and ambitious formats to manage the shared challenges of the 21st century, democratic countries can use other, already existing, frameworks for more fruitful dialogue.

Likewise, democracies can reinforce their moral leadership by distancing themselves from the abuses of autocratic regimes, as Biden has just done by withdrawing US support for Saudi Arabia’s offensive in Yemen.

If anything has become clear of late, it is that democracy is not usually lost in the blink of an eye. It is often eroded little by little, almost unnoticed day to day. In order to rebuild it, a piecemeal approach – instead of grand global gestures – may prove most effective. By working patiently from the bottom up, and from the local to the international, we can still help democracy regain its lustre.

Related Articles: