The repatriation plan between the Bangladeshi and Myanmar governments to return Rohingya refugees back to Myanmar has been postponed indefinitely again amid growing concerns on the wellbeing of returning refugees.

Last month on 30 October, the Bangladeshi and Myanmar governments reached an agreement to begin the repatriation of hundreds of thousands of Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh this month. This comes after two earlier repatriation deals that were planned this year which eventually got scrapped due to similar concerns.

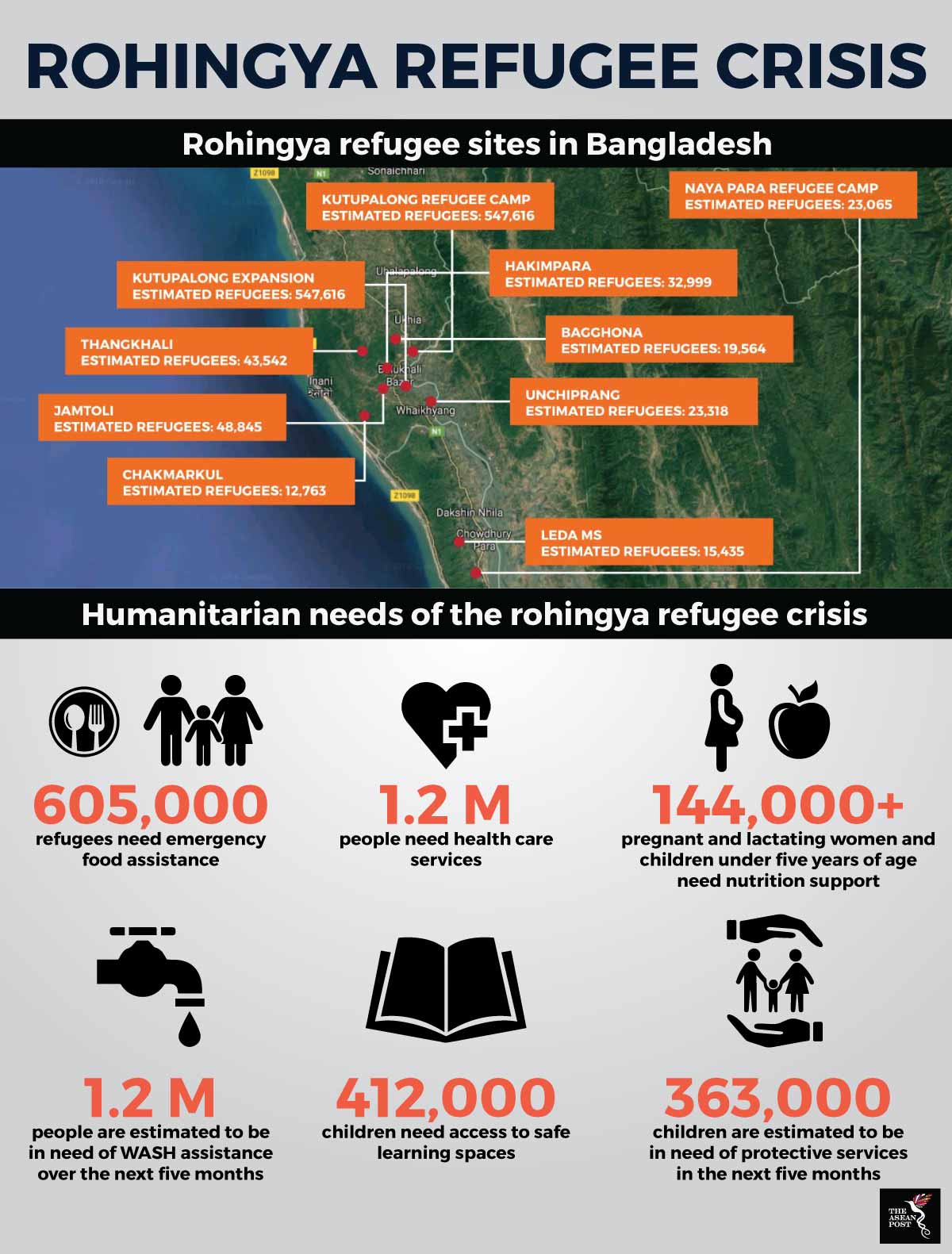

Ever since the latest round of violence against the Rohingya occurred in August last year, more than 650,000 Rohingya refugees have fled Myanmar, crossing the border into Cox’s Bazar in Bangladesh. The Rohingya Muslim community has faced decades of systemic oppression in Myanmar and the latest exodus into Bangladesh is one of many instances of the Rohingya fleeing junta-controlled Myanmar.

The Myanmar government has received intense backlash for its treatment of the Rohingya. In August, the United Nations (UN) called for top Myanmar military officials to “be investigated and prosecuted” for genocide of the Rohingya people in the northern Rakhine state as well as for crimes against humanity and war crimes under international law. The leader of the Myanmar government and former human rights icon Aung San Suu Kyi has also received widespread criticism for her implicit behavior on the crackdown on the Rohingya Muslims. Recently, Amnesty International stripped her of its highest honour, the Ambassador of Conscience Award.

Safety not guaranteed

One of the largest concerns many critics have of the repatriation plan is that the refugees could return to conditions which made them flee in the first place.

“Given the scale and horror of the abuses inflicted on the Rohingya, any arrangement on returns must first address the conditions of apartheid that the Rohingya have fled from,” said Charmain Mohamed, Head of Refugee and Migrants Rights at Amnesty International.

Source: Various

Source: Various

Myanmar has insisted that it is willing to take back every single refugee. Despite that, the country shows no signs of guaranteeing the safety of the Rohingya. The government there still refuses to acknowledge its role in the violence against the Rohingya. Government officials have consistently denied charges by the UN that the country is engaging in “ethnic cleansing” and has even claimed that it was Rohingya militants that burned down the villages where the Rohingya were living. This has raised concerns that the Rohingya would be returning to the same conditions they ran away from in the first place, thus perpetuating the vicious cycle of violence.

The Myanmar government has also failed to grant citizenships to returning Rohingya Muslims. The Myanmar authorities stopped recognising the Rohingya after a law was amended in 1982 that excluded the group from a list of 135 “national races” recognized by the predominantly Buddhist country.

There is also the question of shelter for the Rohingya refugees. One of the reasons why the refugees fled was due to having their homes and villages burnt. In the initial repatriation plans put forward in January, Myanmar said that upon arrival, the refugees would stay in temporary state-built camps. The worry here is that the returning Rohingya will face having to live in conditions worse than what they faced in the Bangladeshi refugee camps.

The Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh are having to live in squalid conditions. The camps there are crowded, while water and food are scarce. However, despite living in such conditions, many still prefer to remain in the camps instead of returning to Myanmar.

Apparently among the reasons why the most recent repatriation plan failed was because none of the refugees wanted to return. Local reports have shown that those who were selected to be repatriated last week have refused to be sent back.

A fact-finding mission by the ASEAN Parliamentarians for Human Rights (APHR) to Bangladesh earlier this year found that many Rohingya refugees have expressed the desire to be repatriated but with several conditions. “They want to return to their homeland, but only if their conditions are met. These include citizenship, justice, compensation, and security guarantees. In any discussions of possible repatriation, these and other demands of the refugees must be heeded, and their human rights must be respected,” said a spokesperson for the APHR.

So far, any repatriation deal seems to ignore the concerns of the victims of violence, the Rohingya refugees. Until their safety and dignity is guaranteed by all parties, any repatriation deal will only end in failure.

Related articles: