Thais are expected to head to the polls in November this year to democratically elect a new government after being ruled by a military government since 2014. However, the ruling junta has demonstrated a pattern of delaying a vote often citing security issues.

Speaking at the Regional Outlook Forum organised by ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute, Thitinan Pongsudhirak, Director of the Thai Institute of Security and International Studies remarked that the junta’s legitimacy has passed its best-before date. Having been plagued by corruption scandals and poor economic management, politicians, civil activists and the general public are restless for elections and a change from the diktats of military rule.

Strengthening the military’s grip

The country is no stranger to military coups and constitutional re-writes. To date, it has gone through 19 constitutions and there have been 13 successful military upheavals in the last 85 years.

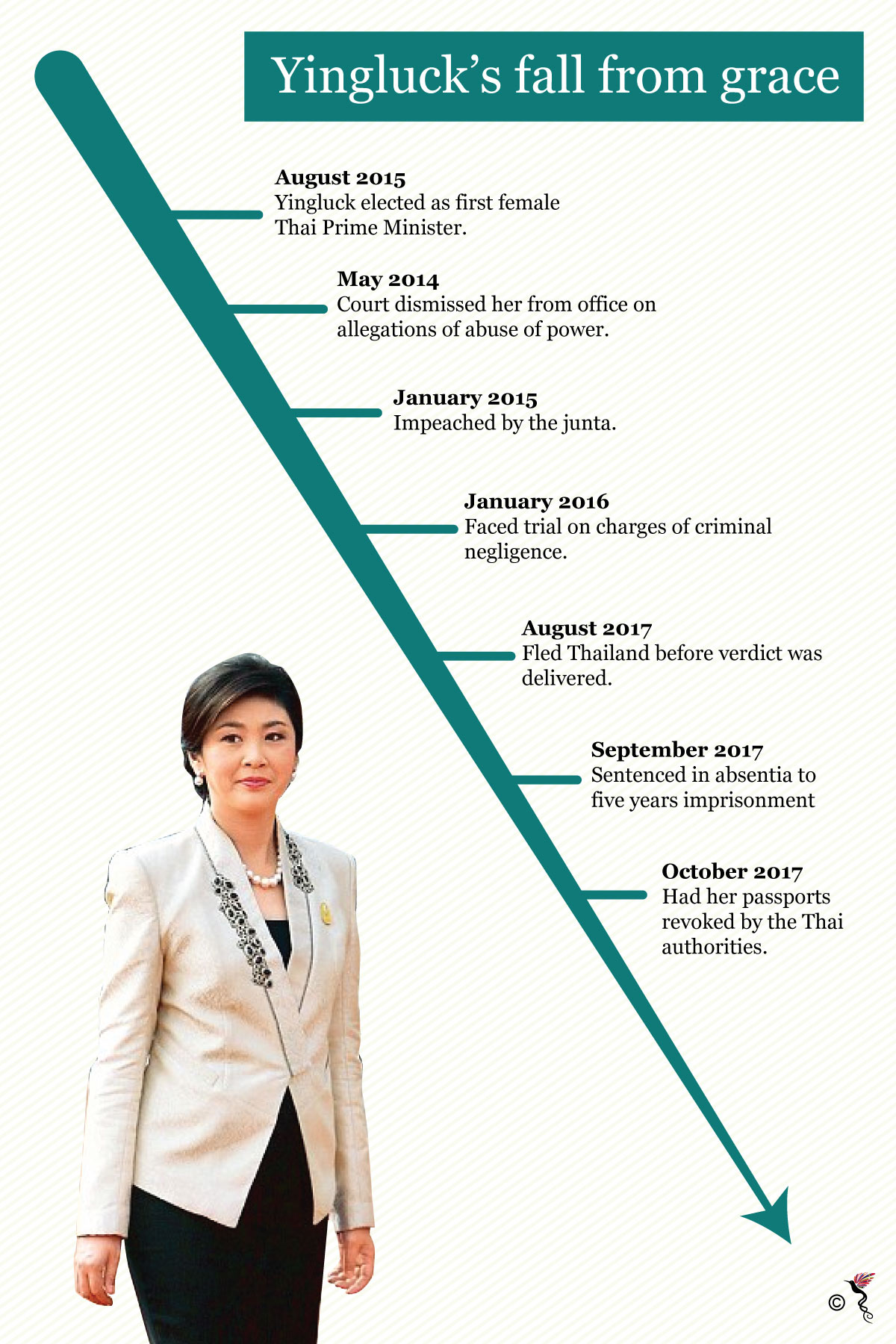

The last military putsch was spearheaded by General Prayut Chan-ocha in 2014. He then unilaterally assumed the position of Prime Minister after the ouster of then Prime Minister, Yingluck Shinawatra.

Upon seizing power, the Thai generals, organised as the National Council for Peace and Order, set to restructure the broken structures of their country’s politics. Their aim was to prevent a future situation where they would have to mount another coup.

Hence, they began work on drafting a new constitution – the 20th in Thailand’s history. However, their initial attempt in 2015 failed as the junta themselves withdrew an initial draft constitution for fear that it may not merit the public’s approval.

They finally succeeded in passing a new charter through a referendum amid criticisms that the process failed to comply with international standards for a fair referendum process. Campaigning was banned and voters had little knowledge about its contents before heading to the polling booths.

“Instead of the long-promised return to democratic civilian rule, the new constitution facilitates unaccountable military power and a deepening dictatorship,” said Brad Adams, Asia Director of Human Rights Watch.

More than 60 percent of the population, however, supported the new constitution with analysts also pointing to political fatigue as being a reason for citizen’s approval. The constitution contains provisions that permit the junta a share of seats in parliament and allows the military to play a role in choosing the Prime Minister – relegating the need for the position to be filled by an elected member of parliament.

Besides that, a proportional representation electoral system enshrined in the new charter makes it extremely difficult for a single party to win a majority in the houses of parliament. Critics claim that this is to ensure the government is always made up of loose coalitions that can be easily separable by the military junta when necessary. The new constitution also requires the government and parliament to adhere to the junta’s 20-year reform plan.

A new political era for Thailand beckons

According to Pongsudhirak, what Thai politics needs is harmony between the forces of military, monarchy and bureaucracy – the key elements which have shaped modern day politics in Thailand through the years.

Prayut’s government also holds an ounce of legitimacy thanks in part to a royal endorsement by the late King Bhumibol Adulyadej. Thai society have always venerated the monarchy especially the king – King Bhumibol himself was considered by many as close to divine.

But the public is fast losing its patience with the military. Amid cases of corruption and continued postponement of the elections, there is only so much its citizens can tolerate before descending onto the streets again.

Pongsudhirak also argued that democracy in Thailand isn’t all about holding elections but also the sustainment of instilled values and institution building and the capacity of exercising them. He believes that a “civilian-military power sharing agenda” could be a useful starting point for political stability in the country.

In reflecting on the future of the Thai political climate, Pongsudhirak opined that the monarchy under the new King, Maha Vajiralongkorn, son of the late King Bhumibol Adulyadej will play a crucial role in Thailand’s path towards a revitalised democracy. Just like how King Bhumibol was a leading figure of moral authority for the Thais, his son can be somewhat similar in safeguarding political stability for Thailand in the long run.

Recommended stories: