As crude prices hover around US$75 a barrel, power producers are feeling the pinch and passing on the cost to customers.

Malaysia’s utility company, Tenaga Nasional (TNB) imposed a 1.35 sen (US$0.0135) per kWh surcharge to offset its fuel and generation costs this month. Although the hike will affect commercial and industrial users, it is likely to increase prices for consumer goods and services downstream.

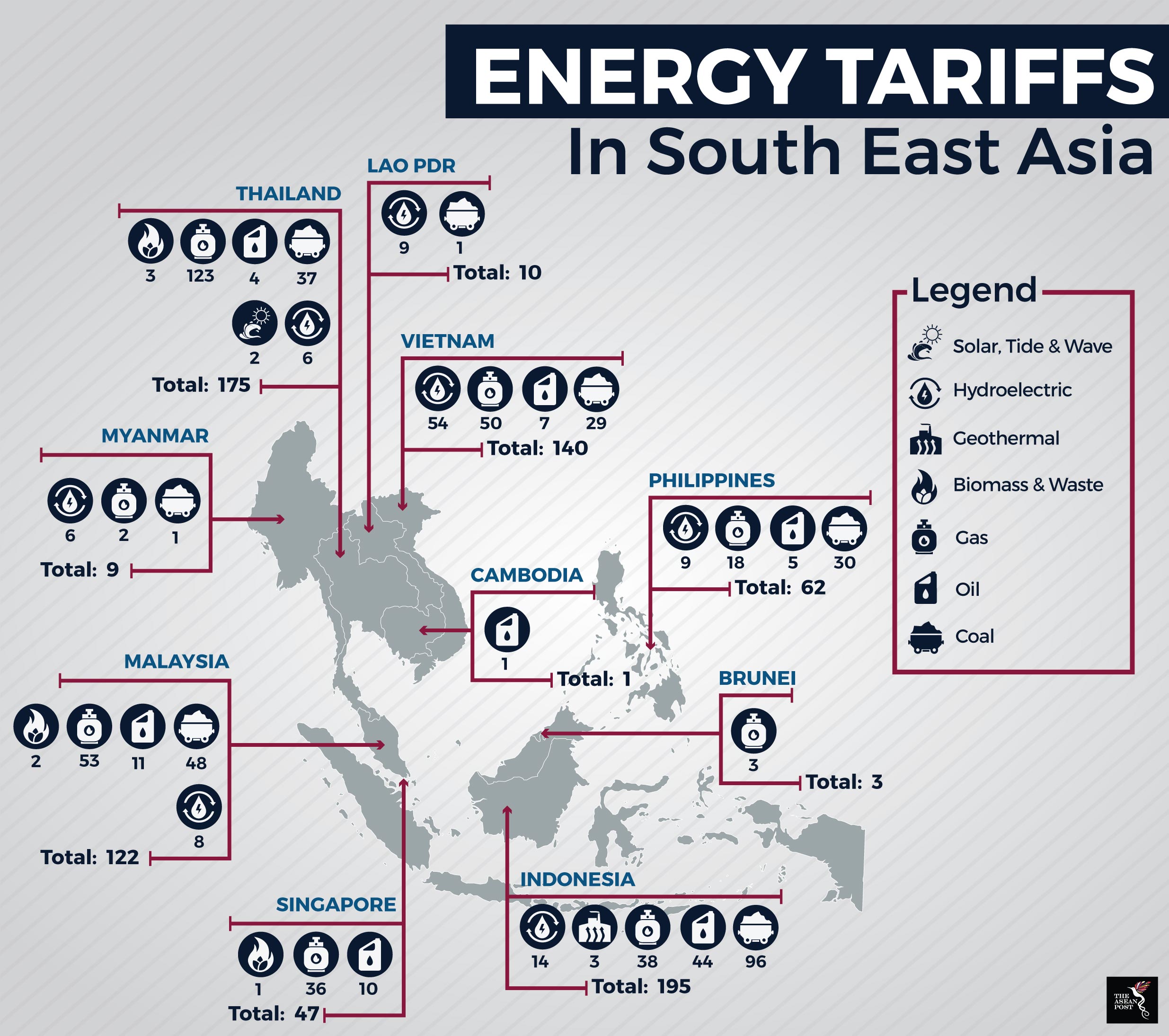

Singapore raised its tariffs to SGD0.2215 (US$0.16) per kWh for April to June 2018, up from SGD0.2156 (US$0.16) in the first quarter of 2018 and SGD0.2030 (US$0.15) in the previous quarter. Thailand charges a base rate plus a fuel tariff (ft) which was increased in the last quarter of 2017.

Interestingly, many power plants utilise natural gas and coal, not crude oil. In Malaysia, oil-fired plants contributed only 0.37 percent of total electricity generation, compared to natural gas (42.54 percent), coal (43.65 percent) and hydro (13.36 percent). Natural gas contributed to 95.5 percent of Singapore’s electricity needs.

Natural gas is a by-product of crude oil drilling. However, there is no pricing benchmark for gas trade. Prices of natural gas and crude oil have historically shown a positive correlation. As such, natural gas prices in Asia are pegged to crude oil prices which in turn affect electricity tariffs.

Indonesia is determined to keep prices of subsidised fuel and electricity stable until the end of 2019, fearing a hike may affect consumer spending power and disrupt its economic growth. Rate hikes lead to high production costs and increase the price of goods and services which may dampen consumer confidence and reduce spending.

Malaysia’s consumer rates are cross-subsidised by the industrial and commercial sectors. If the price of crude oil continues to rise, the government there may be hard-pressed to sustain additional subsidies given its revelation of the poor state of its coffers.

Oil prices started rising in 2017 when the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) and several non-OPEC producers led by Russia reduced their output.

The National Australia Bank (NAB) said in its July outlook, “A key driver of the rise in prices has been the OPEC-Russia deal to cut oil output, compounded by collapsing Venezuelan production and the United States (US) decision to end the Iran deal.”

Its forecasts “point to Brent spending the next few months largely in the mid-to-high US$70s range, although meaningful OPEC-Russia output increases could push prices lower later in the year and higher US shale production should impose an upside limit on West Texas Intermediate (WTI).”

US President Donald Trump issued a strong Twitter message on 4 July to OPEC demanding they reduce prices immediately causing prices to fall the following day to US$77.70 (Brent) and US$73.88 (WTI) per barrel.

Source: Various Sources

Alternative energy sources

As a country’s economic development is highly dependent on energy availability, it needs to diversify its energy mix to ensure security.

Thailand imported 60 percent of its energy needs in 2016. In 2015, it launched a 20-year Power Development Plan which included a goal to have one-third of its energy needs coming from renewable energy. It recently raised that figure to 40 percent.

“We have met half the renewable power target within two years (as at 2017),” said Areepong Bhoocha-oom, chairman of the Electricity Generating Authority of Thailand (EGAT) and permanent secretary at the Energy Ministry. “If the government wants us to increase the proportion of renewable energy, it will not be that hard.”

Lao PDR capitalises on its terrain to generate hydro-power. It currently has 39 hydro-power plants and will have over 90 in operation by 2020. It exports electricity to Thailand, Vietnam, China, Cambodia and Myanmar.

Another power generation option is nuclear power. It is a clean power source that does not discharge any gases and runs reliably under all weather conditions, unlike solar and wind generators.

The Philippines started work earlier on its first nuclear power plant in 1973. However, a safety inquiry following the 1979 Three Mile Island accident in the US, found over 4,000 defects at the Bataan Nuclear Power Plant. The plant was also built on a tectonic fault and close to the then dormant Pinatubo volcano. Pinatubo erupted in 1991.

Safety fears have given pause to nuclear power use in ASEAN, especially after the Fukushima disaster in 2011. Indonesia has legislation that stipulates nuclear to only be considered as the last option. Malaysia may start building a nuclear power plant after 2030. Thailand decided to review its plans after Fukushima.

Lao PDR, Cambodia and Myanmar have not committed to any plans to introduce nuclear power but have signed bilateral agreements with Russia on nuclear power cooperation. Singapore declared it will not be going nuclear.

Until ASEAN nations look beyond traditional gas- and oil-fired generators for its energy needs, their electricity tariffs will continue to rise and fall with crude oil. Subsidies may blunt the effects but ultimately, consumers will have to foot the bill.