The Rohingya are described as being “the most discriminated people in the world” by the United Nations (UN). They are one of Myanmar’s many ethnic minorities. However, the government of Myanmar refuses to recognise them as its citizens. In 2017, a deadly crackdown by Myanmar’s military – also known as the Tatmadaw – on the Rohingya Muslims sent many of them fleeing the country. According to Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), a humanitarian medical organisation, an estimated 6,700 Rohingya were killed in the violent episode.

The UN described the alleged mass killings and rapes of the Rohingya by the Tatmadaw as a “textbook example of ethnic cleansing”. Nevertheless, the government of Myanmar has denied all allegations of genocide.

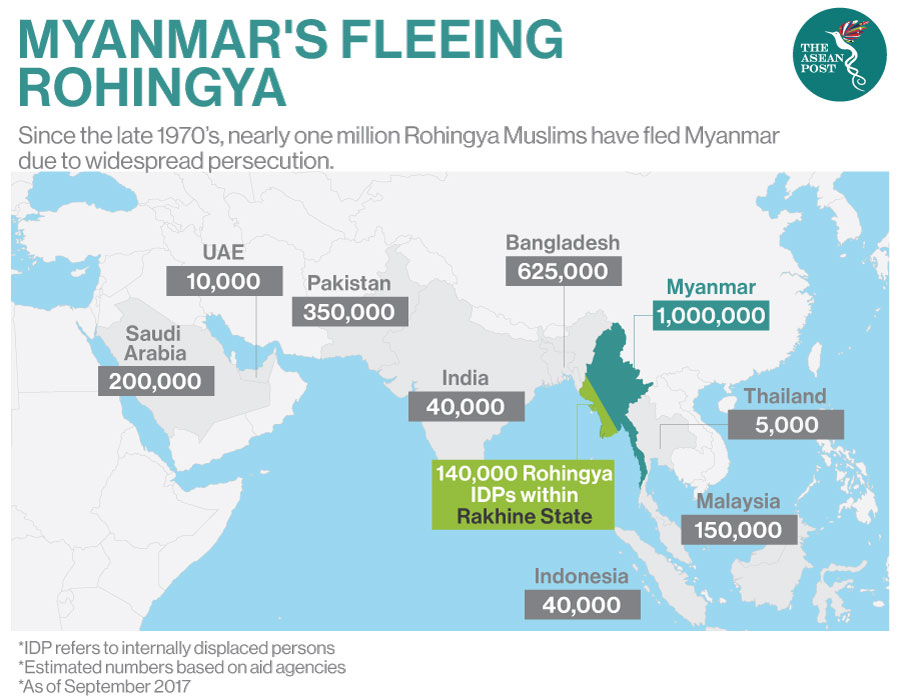

Following the alleged violence against the Rohingya Muslims in Myanmar, hundreds of thousands of them have fled the country to escape abuse and discrimination. Some of the countries they have journeyed to include Bangladesh, Malaysia and Pakistan. According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), Kutupalong in Bangladesh is home to more than 600,000 Rohingya refugees alone, making it the largest refugee settlement in the world.

With the current COVID-19 pandemic affecting livelihoods and plunging the global economy into a recession, many observers and humanitarian organisations are questioning the wellbeing of the Rohingya who are languishing in crowded refugee camps. As of 7 April, Myanmar has reported 22 positive cases of COVID-19 with one death. Compared to neighbouring Thailand which has reported over 2,000 cases, the low number of reported cases in Myanmar has invited scepticism from observers around the world. Many claim the reason for the low numbers of reported COVID-19 cases is simply because of limited test kits available and poor health infrastructure. This has triggered concerns that the actual number of cases in the impoverished country could be much higher than what has been officially reported.

According to international human rights advocacy organisation, Human Rights Watch (HRW), displacement camps with an estimated 350,000 people in Myanmar are simply “COVID-19 tinderboxes”. Overcrowded camps with severely substandard healthcare and inadequate access to proper sanitation have made the communities incredibly vulnerable to the coronavirus. While nations around the world are urging their citizens to self-isolate and practice social distancing, these measures seem to be luxuries that are simply impossible to implement in these squalid camps.

“Health conditions are already disastrous for displaced people in Rakhine, Kachin, and northern Shan camps, and now COVID-19 is threatening to decimate these vulnerable communities,” says Brad Adams, the Asia Director of HRW.

In central Rakhine State, where over 100,000 Rohingya Muslims have been confined to detention camps, daily essentials are critically inadequate. One latrine is said to be shared by as many as 40 people and one water access point by up to 600, according to HRW.

Internet Shutdowns Making Things Worse

It was reported that the government of Myanmar has also imposed restrictions on mobile internet communication in Rakhine and Chin states since June 2019. Currently, nine conflict-affected townships and an estimated one million people inhabit these two states. According to the UN, “it is essential that governments refrain from blocking internet access… especially at a time of emergency, when access to information is of critical importance, broad restrictions on access to the internet cannot be justified on public order or national security grounds.”

The same situation is occurring in Rohingya refugee camps in Cox’s Bazar, on the coast of the Bay of Bengal in south-eastern Bangladesh. According to media reports, authorities in Bangladesh are making efforts to inform and advise those in camps about the pandemic through loudspeakers and megaphones placed in settlements. Schools, learning centres and places where people tend to gather have also been ordered shut over virus fears. Only essential services will be allowed to continue in the camps. However, activists and rights groups claim that this is simply not enough. In September 2019, the government of Bangladesh shut down most of the internet and telecommunications networks in and around the camps, based on media reports.

John Quinley from Fortify Rights, an organisation advocating human rights, urged authorities to lift internet restrictions; this is “so that refugees have information, and are able to inform themselves about how to mitigate the risks of a coronavirus spread in the camps,” he explained to the media.

With inadequate aid, crowded living conditions that make it difficult to practice social distancing, limited access to basic hygiene and clean water, and with no means of communication, communities in displacement and refugee camps are left defenceless.

“If the coronavirus came here, it would be very dangerous for us. We don’t have access to primary medicine here for regular medical treatment, so how can we do such big treatment?” questioned Haroon Rashid from Rohingya Youth for Legal Action, a camp-based civil society group.

Related articles: