More than half a million Rohingya refugees have fled the atrocities in the Rakhine State to neighbouring Myanmar since the latest spate of violence began end of August. The fleeing Rohingya have accused Myanmar’s military (Tatmadaw) and ethnic Rakhine Buddhists of burning their villages to the ground while mercilessly killing Rohingya Muslims including women and children.

“Human beings cannot be tortured that way regardless of ethnicity,” President of the UK based Burmese Rohingya Association, Tun Khin told The ASEAN Post in reaction to the ongoing violence.

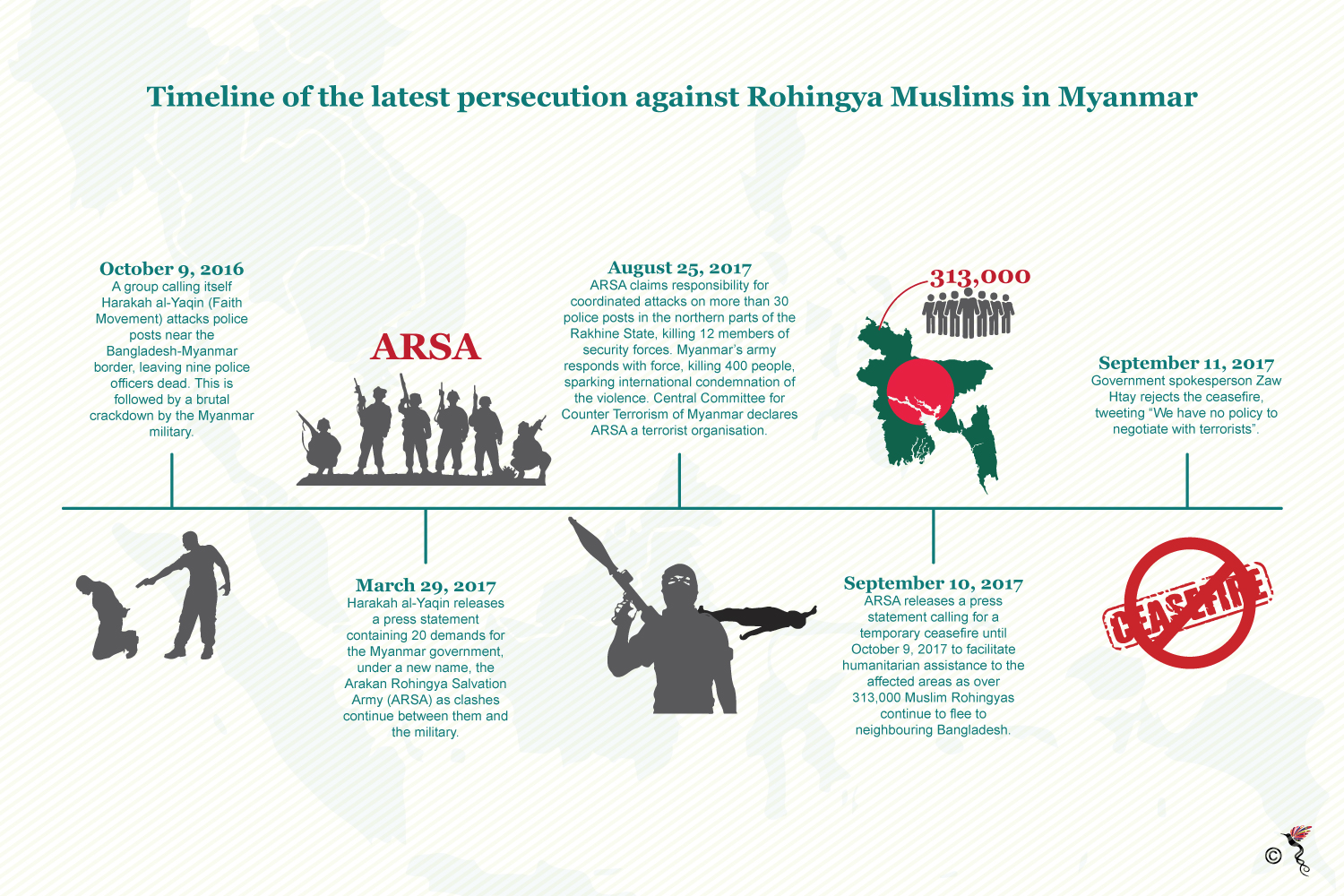

The brutal killings by the Tatmadaw were sparked by the attack on Myanmar border posts by the ARSA (Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army) – a Rohingya insurgent group which the Myanmar government have branded terrorists.

Timeline of the recent persecution of the Rohingya.

The humanitarian crisis has induced some form of a response from the country’s leader and Nobel Peace Prize laureate, Aung San Suu Kyi. However, the international community continues to condemn the leadership of Myanmar for not taking sufficient action and for failing to keep to promises of allowing international observers to the crisis hit region.

European Union President, Donald Tusk on Friday urged Myanmar to adhere to its international rights obligations and allow displaced refugees to return to their homes after fleeing persecution.

“The EU continues to assume its responsibilities by receiving people in need of protection and by assisting host countries close to the conflict zones. We addressed the situation in Myanmar and the Rohingya refugee crisis. We want to see de-escalation of tension and the full adherence to international human rights obligations as well as full humanitarian access so the aid can reach those in need,” said Tusk, as quoted by the AFP.

The persistent persecution of the Rohingya Muslims has dangerously sparked Islamic fundamentalist groups within Bangladesh who have called for Dhaka to arm Rohingya insurgents to fight against their oppression.

On Friday, 15,000 Islamic hardliners marched in the Bangladeshi city of Chittagong against the killings of Muslims in the Rakhine State. The march was organised by organised by Hefazat-e-Islam – a hardline Islamist organisation.

“We demanded a halt to the genocide of the Rohingya. We have also asked the government to train and arm the Rohingya so that they can liberate their homeland,” Hefazat spokesman Azizul Hoque Islamabad told AFP.

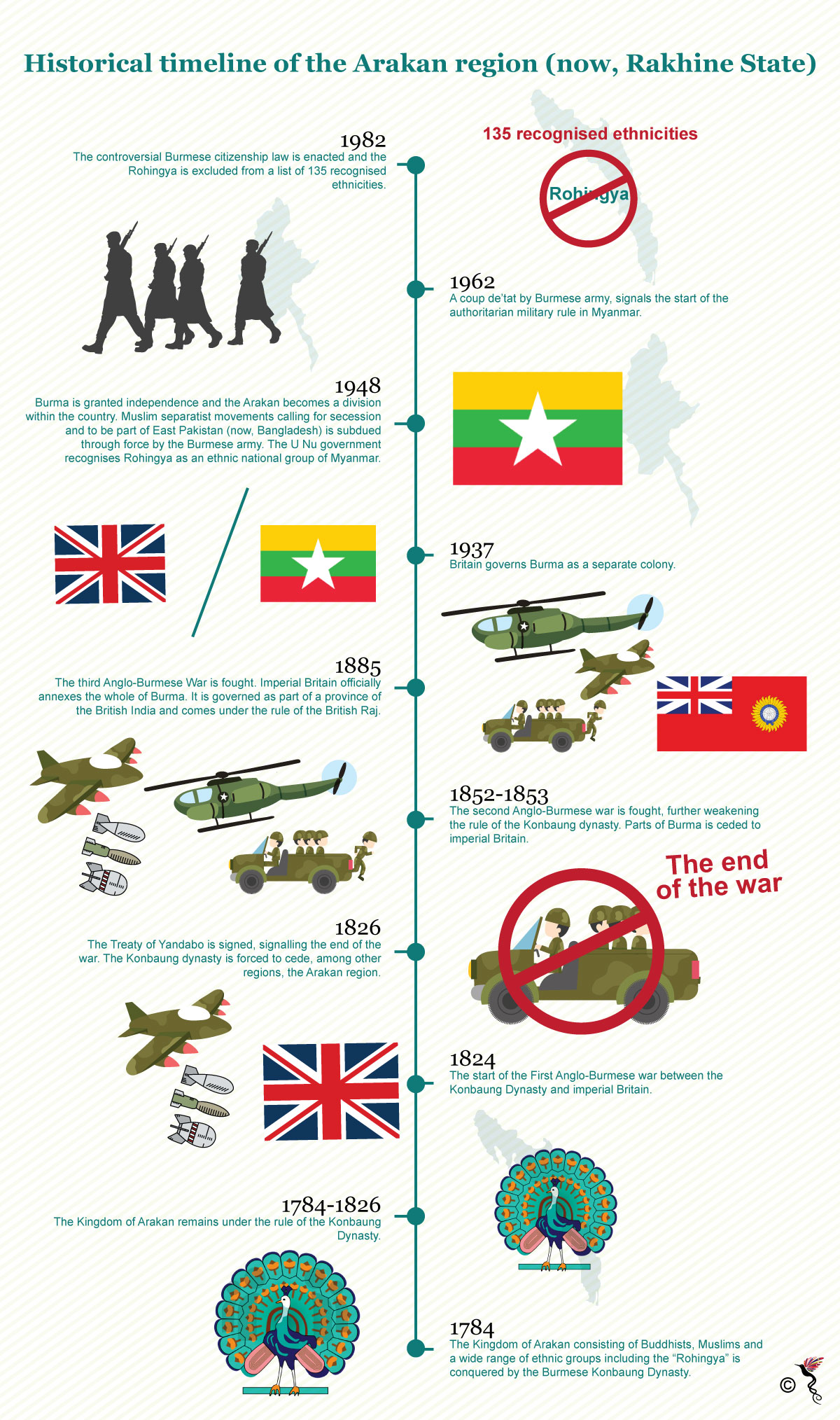

Islamic communities in Chittagong share similar cultural, religious and linguistic ties which can be traced back to then domestic migration within British controlled India. It is this shared heritage which is often exploited as a reason for Myanmar’s authorities to consider the Muslim Rohingya as Bengali immigrants from Bangladesh.

Timeline of the history of the Arakan Region in the present day Rakhine State of Myanmar.

Increased sentiments like these can very well be a precursor to radicalisation. ARSA – which previously declared a ceasefire to allow for passage of humanitarian aid to reach conflict areas – has announced an end to that ceasefire starting on October 9. However, it is unclear if that would mean continued attacks from their side.

Videos and pictures of Rohingya Muslims who managed to escape to live in refugee camps showed them living in squalor conditions, unable to receive adequate food, drinking water and medical supplies. They have been continually denied citizenship and remain stateless to this day. Hence, there is very little motive for the Rohingya Muslims to want to play by the rules and if the situation isn’t reigned in quick enough, young Rohingya Muslims could be the first to be radicalised to take arms against their government.

This will be a scenario that benefits no one. Another military conflict in ASEAN’s backyard – the other being the insurgency in Marawi in the Philippines – will only spell trouble and humiliation for the region. Humiliation, because the organisation has thus far failed to perform any palpable action to remedy the situation from getting out of hand – often hiding behind the veils of the principle of non-interference.

According to Michael Vatikiotis, Asia Regional Director for the Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue who spoke during the 2017 ASEAN Roundtable organised by the ISEAS- Yusof Ishak Institute, ASEAN has thus far failed to rise to the challenge.

“The main obstacle is the principle of non-interference. ASEAN must make an exception to this rule when it comes to the conflict in Rakhine state or even the insurgency in Marawi,” he said.

The situation is undoubtedly getting from bad to worse given the latest threats of radicalisation. And every day people continue to make the dangerous pass from Myanmar to Bangladesh, it only demonstrates the weakness of the international community and Myanmar to find a resolution to this crisis.

Until then, how many more people must suffer?