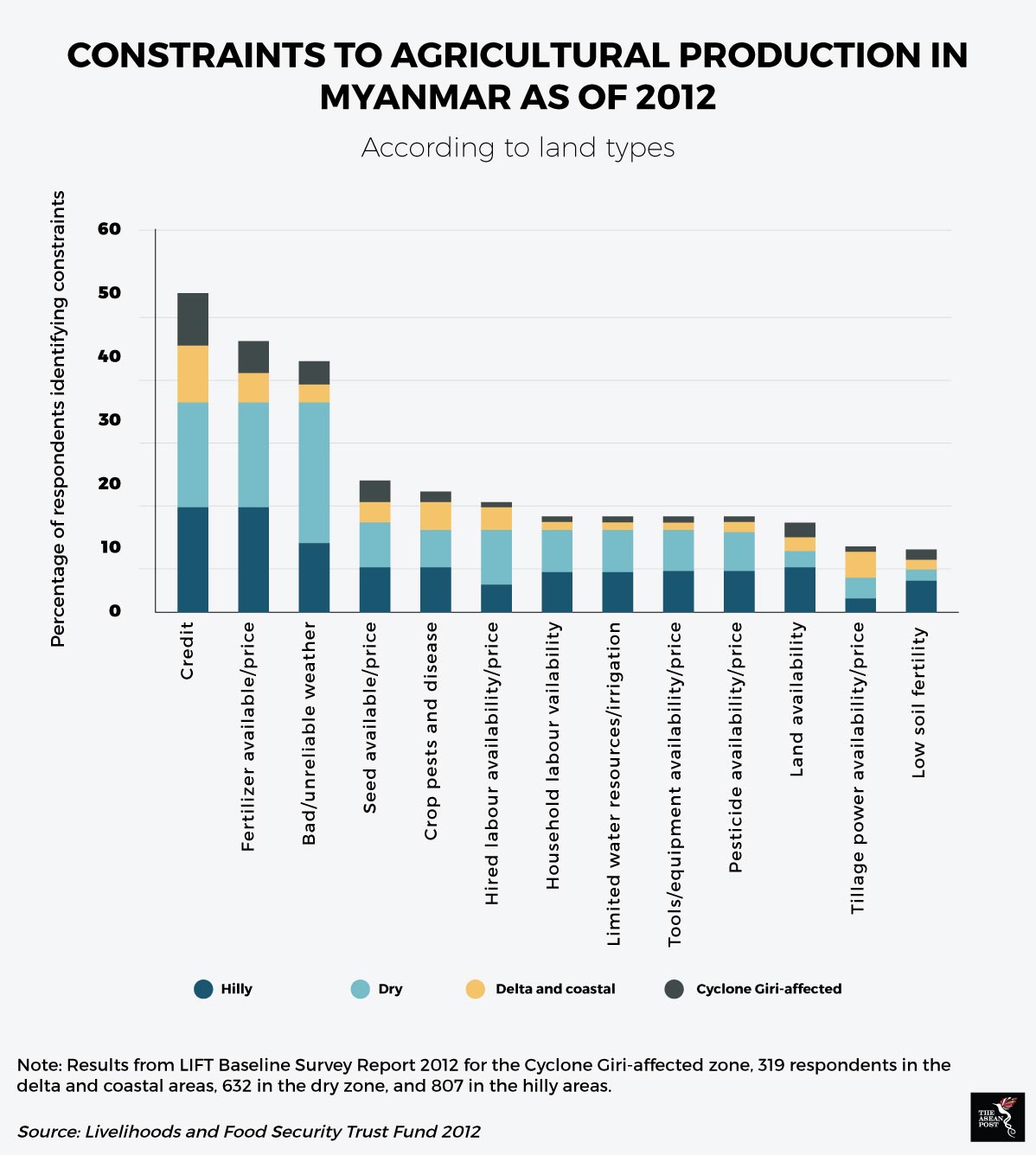

Myanmar’s agricultural sector faces a myriad of problems, such as a shortage of trained farmers, a rural infrastructure and lack of crop diversification. According to the 2015 ADB report on Unlocking the Potential for Inclusive Growth, this is in part due to financing barriers resulting in a lack of resources to invest in quality farming equipment

Agriculture accounts for 38% of Myanmar’s GDP and 23% of exports in 2016, according to the World Bank.

In terms of financing, many farmers have only been able to obtain small loans from the Myanmar Agricultural Development Bank (MADB), which isn’t enough for them to diversify their crops, purchase land and invest in new tools. They then supplement the MADB loan or try to repay it by taking on secondary loans from informal moneylenders. This in turn puts them into a debt cycle as reported by The Economist in 2017.

Conversely, these farmers’ inability to repay their loans affects MADB’s ability to extend lending facilities to other needy farmers. In 2016, MADB had a fixed fund volume of K1.7 trillion a year from the government. According to the deputy permanent secretary of Myanmar’s agriculture ministry, U Myo Tint Tun, only K10 billion was repaid from a total of K1.4 trillion worth of loans granted that same year.

Social entrepreneurships refer to the use of business models to effectively address social and environmental issues. Although profit-generating, any returns on investment are usually funnelled back to the farmers rather than distributed among investors. Such business models can help Myanmar farmers leverage on connections, technical know-how and financing that they would not normally have access to.

One such social entrepreneurship, Proximity Designs, helps farmers by designing low-tech tools at lower prices which can be used to improve farm yields. The company also does foot-powered water pumps, and portable storage water tanks. In 2012, it released a range of affordable solar lighting that reduces lighting costs by 60% and can last up to two years.

These tools are sold and not given to farmers to instil a sense of ownership over their own productivity.

“They’re not charity recipients or aid beneficiaries. It’s a relationship of mutual exchange and power. You see, if you give something away free you never know whether it’s used or valued,” said co-founder Debbie Aung Jin at the We The Future event co-organised by the United States Foundation and Skoll Foundation in September 2017. The revenue is then channelled back into Proximity Designs research and development.

Proximity Designs began business in 2004 as the country office of International Development Enterprises. One of its first projects was to build irrigation tools for the 600 villages it had access to. The aftermath of Cyclone Nargis in 2008 led it to diversify its offerings, including creating farm recovery services to address crop failings. It also began to offer farmers training in more effective farming techniques.

This social entrepreneurship has also began offering microfinancing to farmers, under its microfinancing arm, Proximity Finance. Proximity Finance signed an agreement with Yoma Bank in 2017 to provide financing to 28,000 farmers, using hedge financing. Proximity Finance currently supports a client base of 78,000.

Social entrepreneurship Impact Terra meanwhile, uses an app called Golden Paddy to train farmers in Mandalay, Shan State, and Bago. Farmers are given the most relevant information based on their region and crop type. Impact Terra is also working with the European Space Agency to install satellite data to provide real-time weather updates to farmers in specific locations.

One of the challenges for a social entrepreneurship is to stay solvent. “Proximity Designs is one of Myanmar’s social enterprises that has succeeded in breaking even,” said Tristan Ace, a project manager for Myanmar at the British Council.

Despite obvious financial challenges, social entrepreneurships could potentially help Myanmar’s farmers solve their problems faster and more efficiently.

Recommended stories: