It’s been sagaciously said that the love of money lies at the root of all evil.

Experience tells us that this is so, and therefore it could be also said that the vice of corruption or bribery as an element of the “original sin” of the love of money constitutes a root – as part of the wider root - of all evil.

Corruption defined properly in broad terms and inclusively ranges from the simple giving of a bribe to misappropriating and embezzlement of public funds through the procurement process under the cloak of authority. It is a cancer that eventually enervates and corrupts society as a whole when considered in relation to the entire political and administrative system that enables it to thrive.

This results in the breakdown of moral fibre and trust which in turn is epitomised by institutional and systemic derelictions and failures. Or to put it in a slightly but just as vivid manner: corruption is the gangrene – i.e., the death of tissues – that will eventually destroy the whole body if pre-emptive action is not taken.

As it is, corruption is given global recognition with the designation of 9 December every year as International Anti-Corruption Day.

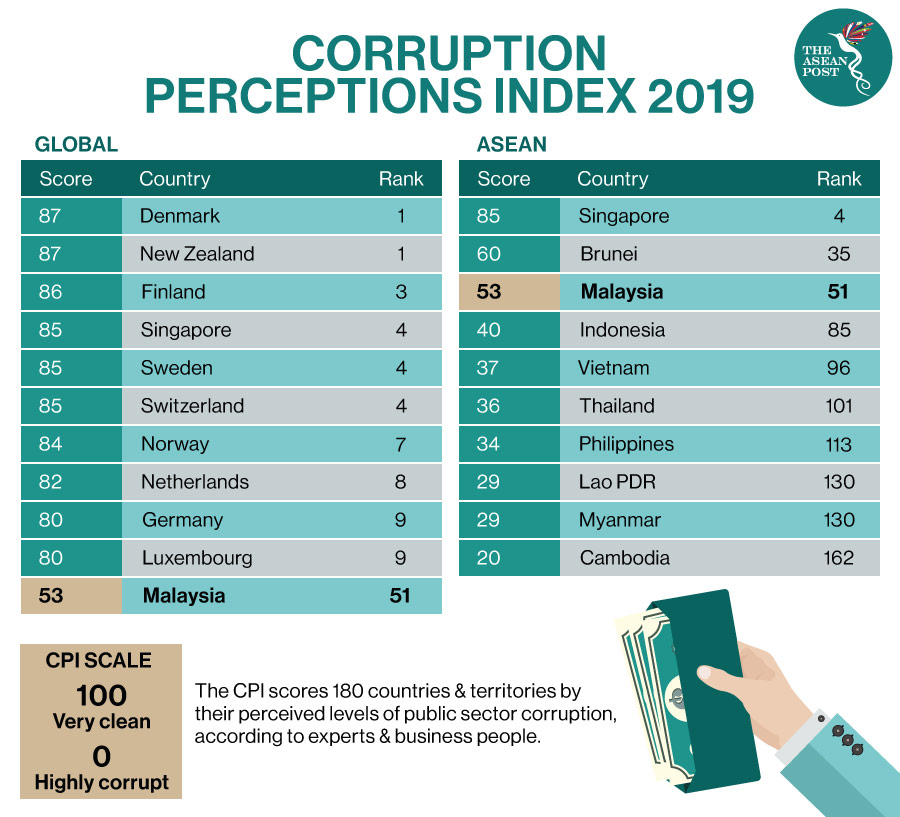

Malaysia has consistently ranked “high” in the corruption index or scale as measured by Transparency International (TI). For 2019, TI’s Corruption Perception Index (CPI) ranks the ASEAN member state at 51 out of 180 countries with a score of 53 out of 100.

The recent high profile of acquittal and discharge not amounting to acquittal (DNAA) of prominent politicians is disconcerting to many Malaysians who worry that this represents a setback to the reforms put in place to root out and reset the nation away from the perceived structural corruption that has given rise to the anecdotal or popular but jaded cliche that the “system is rotten to the core”.

Under the Abdullah administration, the Integrity Institute of Malaysia (IIM) and an independent Malaysian Anti-Corruption Commission (MACC) was formed in 2004 and 2009, respectively.

What is often not known is the fact that in 2011, the MACC introduced a scheme that offered cash rewards to civil servants who whistleblow, equal to the amount of the bribe or kickback or graft involved. Whistleblowers are protected under the Whistleblower Protection Act (2010) and Witness Protection Act (2009).

On the other hand, civil servants can be fined for failure to report the giving of as well as request for bribes. As of December 2020, five civil servants have been fined for neglecting or omitting to report cases of bribery to the MACC under section 25 of the Malaysian Anti-Corruption Commission (MACC) Act (2009).

Whereas based on the same data by the MACC, only 343 civil servants came forward to provide information on corrupt practices between 2012 and last year, according to Deputy Chief Commissioner (Prevention) Shamshun Baharin Mohd Jamil.

More contemporary initiatives include the previous Pakatan Harapan (Coalition of Hope) administration’s National Anti-Corruption Plan (NACP) 2019-2023 – as developed by the Governance, Integrity and Anti-Corruption Centre (GIACC), in the Prime Minister's Department – with its Six Priority Areas that are most vulnerable to corruption, namely: political governance, public sector administration, public procurement, corporate governance, law enforcement and legal and judicial.

In support of the Six Priority Areas, the NACP further outlined the following Six Strategies: (1) strengthening political integrity and accountability; (2) strengthening the effectiveness of public service delivery; (3) inculcating good governance in corporate entities; (4) increasing the efficiency and transparency in public procurement; (5) institutionalising credibility of law enforcement agencies, and (6) enhancing the credibility of the legal and judicial system.

Not least, Section 17A (Amendment, 2018) of the MACC Act (2009) representing strict liability for corporate compliance came into effect on 1 June, 2020 after a moratorium period for adjustments and familiarisation of two years.

This means that “commercial organisations are also liable and can be punished if their employees or associates are involved in corrupt activities and transactions. The commercial organisation could be considered guilty based on whether its top management or its representatives are aware of the corruption committed by their employees or associates”.

The penalty under Section 17A (2) is a fine of “not less than 10 times the value of the bribe or a minimum of RM1 million (US$247,610), whichever is higher, or imprisonment for up to 20 years, or both”. However, an allowance is provided on the condition that “the commercial organisations can demonstrate that they have implemented ‘adequate procedures’ to prevent corruption in their business operations or activities”.

It was announced early this year that some 22 out of the 115 initiatives under the NACP that have been implemented fully under the previous government are the no gift policy and asset declaration. However, when it came to the ban on political support letters and political appointments, there has been some controversy as these initiatives have not been complied with.

Civil society is no less involved and agitated in the drive and fight against the scourge of corruption, particularly in view of the widespread problem in Malaysia.

The nation’s anti-corruption watchdog, the Centre to Combat Corruption and Cronyism (C4) has been quite active in promoting awareness of anti-corruption behaviour through its programmes and campaigns, tracking progress of anti-corruption reforms and developing policy recommendations to further improve and enhance existing anti-corruption measures, among others.

Recommendations

The following policy recommendations by the C4 and fully endorsed by EMIR Research for the Perikatan Nasional government under Prime Minister Muhyiddin Yassin are as follows, namely: (a) the necessity to revive and table the Government Procurement Bill by early next year; and (b) that the Special Cabinet Committee on Anti-Corruption (JKKMAR) be empowered and authorised to monitor and call out those that delay the implementation of the NACP.

On our own, EMIR Research would like to urge that: (1) the placement of MACC officers in selected government-linked companies (GLCs) – whether as members of the board of directors, Chief Integrity Officers (CIOs), etc. – be extended to all from the current list and made compulsory (externally, i.e., provisions in the MACC Act and internally, i.e., in what is now the constitution of the GLCs, formerly known collectively as memorandum of association and articles of association) as part of good corporate governance; (2) the government further enhance the e-Perolehan procurement system and the Project Monitoring System (PMS/SPP) II with the deployment of artificial intelligence (AI) software and blockchain technology, and integrated with the Laksana digital dashboard for real-time and holistic monitoring and oversight and (3) Section 8(1) of the Whistleblowers Act (2010) should be amended to do away with the narrow constraints imposed or placed upon the whistleblower’s reporting capacity.

Just like the battle against the COVID-19 pandemic, the on-going “cosmic” struggle against corruption – as a work-in-progress – is also a matter of life and death metaphorically speaking that entails a whole of government and whole of society approach and effort. Everyone plays a part, big or small, in ensuring that corruption doesn’t become a way of life and a necessary evil in this world.

As we brace for 2021 which should mark the ‘Reform’ phase, may both government and society work together to usher in a new era of hope and aspiration – for a nation that will be relatively corrupt-free in the future.

Related articles: