In a peaceful settlement of international territorial and maritime disputes between states, parties involved have a lot of options including negotiation, inquiry, mediation, conciliation, arbitration, judicial settlement or other peaceful means depending on the dispute.

In the case of the Philippine’s claims to North Borneo or Sabah, based on the Manila Accord of 31 July 1963, entered into by the Philippines, Indonesia, and Malaya – the Philippines has the right to pursue its claim according to the methods of peaceful settlement of disputes as established under international law. Based on the said agreement, the Philippines has the right to resort to methods such as the aforementioned in the settlement of its claim to North Borneo.

Hence, the Philippines has tried many ways. It resorted to diplomatic negotiation and also proposed for a judicial settlement through the International Court of Justice (ICJ) as a way forward toward the resolution of its claims to Sabah. However, Great Britain and the Federation of Malaysia, have not agreed to the proposal of the Philippines to refer the matter concerning Sabah to the ICJ.

Thus, the proposition of the Philippines to settle the conflict over Sabah with Malaysia and Great Britain through the World Court failed.

To note, under international law, a state has no legal obligation or is not compelled to submit to international disputes by any tribunal, except as it may consent or agree to do so.

Also, the methods of settlement on the Sabah Dispute stipulated in the Manila Accord of 1963 can only be utilised and operationalised, when the parties voluntarily consent to resort to any of these means. In this case, it is difficult for the Philippines to settle its claims on Sabah unless Malaysia voluntarily gives their consent to submit the Sabah case for resolution through various international means of settling territorial disputes.

Contentions From Both Sides

Malaysia’s refusal to submit the Sabah Dispute to the ICJ can be best illustrated by what Ghazali Shafie, a Malaysian politician who served as Foreign Minister and Home Minister said in his 10-page speech to the National Press Club in Kuala Lumpur on 6 November, 1968. He remarked that reference of the case to the World Court (ICJ) is irrelevant.

He said, “by nature it is not, strictly speaking, a matter for the Court to decide. A reference to the Court could nevertheless be made, but if the verdict were rendered on narrowly legalistic grounds (as happened in the Southwest Africa case a few years ago), and if it were found that the Philippine legal case was the stronger (which is by no means a foregone conclusion), the result could just be to fan the controversy rather than to resolve it.”

He further claimed that, by far, the overwhelming part of the Philippines claims to Sabah is more political and not legal at all. He concluded that the talks and claims of the Philippines over Sabah is more of domestic political propaganda.

In retrospect, one can discern from the speech of Ghazali Shafie, that Malaysia cannot help but wonder why the Philippines insists on pushing "by peaceful, legal means" a claim which has no prospect whatever of being satisfied except through violent and illegal ones. From the Malaysian vantage point, the present state of affairs must seem far preferable than that which prevailed in 1963, 1964, 1965, or 1968, where diplomatic and bilateral ties between the two countries were at its worst.

In this regard, one has to take cognisance of the fact that, since the time the Philippines pursued its claim on Sabah, there was never any indication on the part of Malaysia to budge from its consistent position that, “there’s no” such thing as a Philippines claim to Sabah, and that the only solution to the affair is the recognition by the Philippines of Malaysia’s right to sovereignty over Sabah.

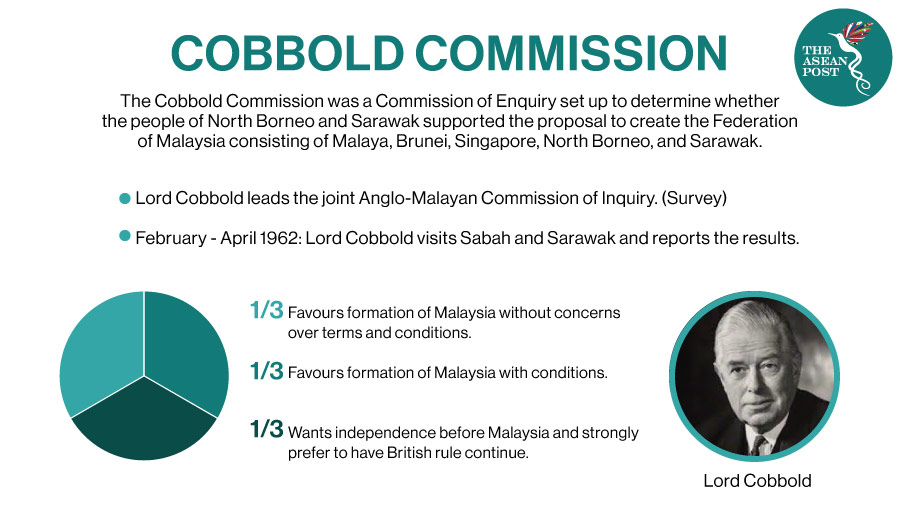

Malaysia stands firm on the findings of the “Cobbold Commission,” which accordingly expressed the conviction that "the people of Sabah have chosen their destiny and affinity to be part of Malaysia over the Philippines.”

However, the Philippines on the other hand, since the time it concertedly pursued its claims on Sabah, has long dismissed the idea that its sovereign claim to Sabah is irrelevant after the United Nations’ (UN) findings based on the Cobbold Commission.

It contends that the UN Mission's conclusions had only obligated the Philippines to refrain from obstructing the formation of Malaysia, but in no way whatsoever obliged the Philippines from giving up its claim to Sabah. The Philippines maintained a contradictory position to that of Malaysia and asserts that it had agreed not to prevent Sabah from joining Malaysia, but that Sabah's inclusion therein was "subject to the final outcome” of the Philippine claim, which to date, has yet to be settled and resolved.

Moreover, despite Malaysia’s rejection of the Philippines’ proposal to refer the issue of Sabah to the ICJ, the Philippines appears and remains determined to press on and remains firm in its conviction of not giving up on its sovereign claim to Sabah. On this note, it would seem worthwhile to explore the legal and historical basis of the Philippines’ claim to Sabah, which forms part of why it is confident to refer the matter to be settled under the auspices of the ICJ to which Malaysia has an outright opposition.

Historical And Legal Basis

The Philippines contends that it has a strong historical and legal claim to North Borneo or Sabah.

From a historical perspective, it is undisputed that the Sultan of Sulu was the sovereign ruler of North Borneo which was ceded to him by the Sultan of Brunei in 1704. Such sovereignty was recognized by Great Britain, Spain, and the United States (US) in treaties which they entered into with the Sultan of Sulu at various times in the 19th century.

For instance, during the Spanish occupation of the Philippines, the Spaniards never deprived the Sultan of Sulu of his sovereignty over North Borneo, in the same manner, that during the American colonisation of the Philippines, the Americans did not deprive the Sultan of Sulu as well of his sovereignty over the disputed territory.

Likewise, the agreement which the Sultan of Sulu entered into with Baron von Overbeck and Alfred Dent regarding concessions in his North Borneo territory was a permanent lease and not a “cession” piece of document. But the British claim otherwise. Nevertheless, the Philippines maintains that the said agreement merely extended power over the British North Borneo Company to administer the disputed territory through the delegated powers of the Sultan of Sulu, and thus the sovereignty over North Borneo remained vested with the Sultan of Sulu.

Whereas, the legal basis of the Philippines’ claim rests on three arguments. First, the cession of 1704 by the Sultan of Brunei to the Sultan of Sulu of the territory of North Borneo in gratitude for the latter's help in quelling a rebellion vested sovereign rights to the Sultan of Sulu over the territory. This is a historical fact.

Second, the lease of 1878 executed by the Sultan of Sulu on 22 January, 1878, in favour of Baron von Overbeck and Alfred Dent was a contract of permanent lease and not a contract of cession as alleged by the British. It could not be otherwise since Overbeck and Dent acted as private individuals. This is supported by the fact that there was a continued payment of annual rentals to the heirs of the Sultan of Sulu by the North Borneo Company until recently.

And thirdly, that the interpretations of the rules of international law regarding a territorial lease strongly support the Philippine claim that sovereign rights could not have been acquired by Overbeck and Dent to the territory of North Borneo. This is because, in international law, a lease agreement between states does not constitute a transfer of sovereignty and there cannot be a transfer of sovereignty to individuals.

Moreover, to determine whether the historical and legal basis of the Philippines’ claim to Sabah are indeed legally strong and meritorious vis-à-vis the claims of Malaysia remains to be seen until the Sabah issue is referred to an international body like the ICJ.

To reiterate, the proposal of the Philippines to submit the territorial dispute over Sabah to the ICJ was rejected not only by Malaysia but even Great Britain as well.

Conclusion

Although the Sabah Dispute between the Philippines and Malaysia is currently in one of its recurrent calm periods; at the end of the day it still remains unresolved.

Thus, it continues to be a speck in the bilateral relations between these two countries, and one way or the other, disrupts the normal relations between Malaysia and the Philippines from time to time, creating rancour and bitterness in the process.

Moreover, under international law, there are a lot of mechanisms and means available that disputing parties could employ to settle the Sabah issue. Therefore, the Philippines and Malaysia should continue to explore and find a peaceful solution to the Sabah dispute.

This is Part Three of the “Sabah Dispute” series of articles.

Related Articles: