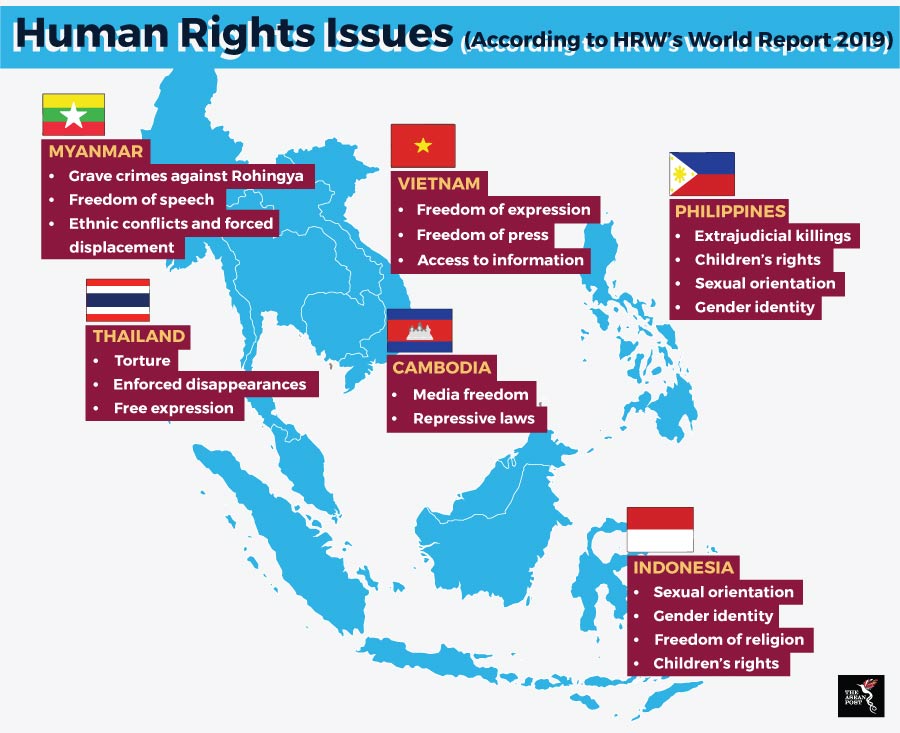

Human rights are fundamental to all human beings, regardless of race, sex, nationality, ethnicity, language, or religion. However, due to the diverse cultures and varying political structures in Southeast Asia, tackling human rights issues remains a major hurdle for the region. The issues faced by all 10 countries in the region tend to overlap each other, ranging from press freedoms, religious freedoms, blasphemy, extrajudicial killings, right up to the issue of gender identity.

While some Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) member countries have made efforts to address the vast range of human rights issues and to protect the rights of vulnerable groups in their communities, there are others still finding it a challenge to move forward.

For example, according to Human Rights Watch (HRW), Indonesia’s government took steps in protecting the vulnerable by banning child marriages and moving eight Moluccan political prisoners more than 2,000 kilometres from a remote high-security prison in Nusa Kambangan to a prison much closer to their families in 2018.

Despite these positive developments, international non-governmental organisation, Human Rights Watch (HRW) has still criticised the Indonesian government by stating in its ‘World Report 2019’, that Indonesian President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo’s had “…failed to translate his rhetorical support for human rights into meaningful policies during his first term in office.”

In the Philippines, HRW stated that the country has worsened its human rights crisis “…as Duterte continued his murderous “war on drugs” in the face of mounting international criticism”.

Up till today, authorities across the ASEAN region continue to arrest and imprison people under draconian laws to stifle freedom of expression, religion and blasphemy. Religious and gender factions are still being harassed and threatened by some authorities and religious extremists.

Human rights defenders

In Thailand, the killing of more than 30 human rights defenders and other civil society activists since 2001 remains largely unsolved while the government’s promises to develop measures to protect human rights defenders continues to go unfulfilled.

Apart from that, defamation lawsuits are frequently used to react against individuals who report on human rights violations in the country. One example would be the case of Sirikan Charoensiri of Thai Lawyers for Human Rights (TLHR) who was charged with sedition that could result in at least 10 years imprisonment if found guilty.

The same pattern is also seen in Myanmar where human rights defenders are under the constant threat of arrest and murder due to the country’s corrupt judiciary practices and weak rule of law. For example, according to the ‘World Report 2019’, in May 2018 “a human rights defender from the Ayeyarwady Region was sentenced to three months in prison under 66(d) for broadcasting a video of a satirical play about armed conflict on Facebook”.

Freedom of religion and blasphemy

The Vietnamese government constantly scrutinises, harasses and conducts crackdowns on religious groups outside government-controlled institutions. Some examples of institutions that face endless surveillance as mentioned in the ‘World Report 2019’ include the unrecognised branches of independent Protestant and Catholic house churches, Khmer Krom Buddhist temples, and the Unified Buddhist Church of Vietnam.

The ethnic Montagnards also face surveillance and mistreatment by security forces which has caused hundreds of them to flee to Cambodia and Thailand for sanctuary. Citing HRW’s report, it was stated that according to the United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR), Vietnam has pressured the United Nations and refugee resettlement countries to not accept Montagnards.

In Myanmar, a country that is more than 80 percent Buddhist, religious minorities, including Hindus, Christians, and Muslims, continue to face threats and persecution.

In May last year, Myanmar authorities sent a letter to a Christian man in Rangoon, warning him not to continue praying in his home with others without first receiving approval from them. Local officials also charged seven Muslims for holding public prayers under the Ward or Village Tract Administration Law.

Indonesia also continues to suppress the religious freedoms of its people. One infamous incident in 2017 was the arrest and sentencing of former Jakarta governor Basuki “Ahok” Purnama, a Christian, to a two-year prison term for blasphemy against Islam. According to HRW, the Ministry of Religious Affairs has also drafted a “…religious rights bill that would further entrench the blasphemy law as well as government decrees making it difficult for religious minorities to obtain permits to construct houses of worship.”

Sexual orientation and gender identity

In late 2019, HRW said that the Philippines showed improvements in treating its LGBT community when it unanimously passed a federal non-discrimination bill back in September 2017 but has noted that they have yet to allow a companion bill.

Sexual orientation in Indonesia is a contentious issue. HRW says that Indonesia “continues to fail to uphold basic rights of LGBT people” as the country derailed its public health outreach program which consequently contributed to the five-fold increase in HIV rates for same sex couples since 2007.

Malaysia has also outright condemned those advocating for the LGBT community. Numan Afifi, an activist for the LGBT community there has often received death threats just because he speaks up for them. Even Malaysia’s own Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad said that Malaysia “cannot accept LGBT culture,” back in September 2018.

Brunei has also been scrutinised for its recent implementation of Syariah law which allows the stoning of anyone found to be LGBT. Stephen Cockburn, Deputy Director of Global Issues at Amnesty International, said that this act is “sickening and callous in any circumstance”. In a response, Erywan Yusof, Brunei’s minister of foreign affairs, said that the implementation would “protects the sanctity of family lineage and marriage”.

The future

If human rights issues are not tackled seriously, development in other areas would seem relatively hollow and meaningless to those being persecuted on a daily basis. Efforts to address such issues together as a region must be done immediately, so that the ASEAN community can live in greater harmony, and continue to strive towards a better future.

There is a genuine need for ASEAN governments to step up and take a stand against human rights abuses. Nevertheless, with changing political climates within each nation, the protection of human rights is not so straightforward. Still, human rights should be the responsibility of society; with all parties acting fast when the need arises.

Related stories:

Myanmar crisis getting out of hand