Former Indonesian general and presidential candidate Prabowo Subianto intends to review infrastructure projects that the country has signed up to as part of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). His brother and campaign leader, Hashim Djojohadikusumo, explained that while there were some good projects under the initiative, there were also unnecessary ones. One such project is the US$4.5 billion high-speed railway currently being built to connect Jakarta and the city of Bandung. The rail project is being funded by loans from the China Development Bank (CDB).

“I think it’s too expensive. We’re talking about a US$4 billion investment for a less than 200-kilometre (km) railway which goes from the suburbs of Jakarta to the suburbs of Bandung,” Djojohadikusumo told foreign correspondents. The railway is about 150 km long.

As Djojohadikusumo’s comments are made in the face of rising resentment among Indonesian locals towards China, there is little doubt that his comments are aimed at increasing support for Prabowo.

Chinese workers

Possibly one of the biggest concerns for local Indonesians is the fact that investments from China and the number of Chinese nationals working in the country do not seem to tally when compared to Indonesia’s other foreign investors.

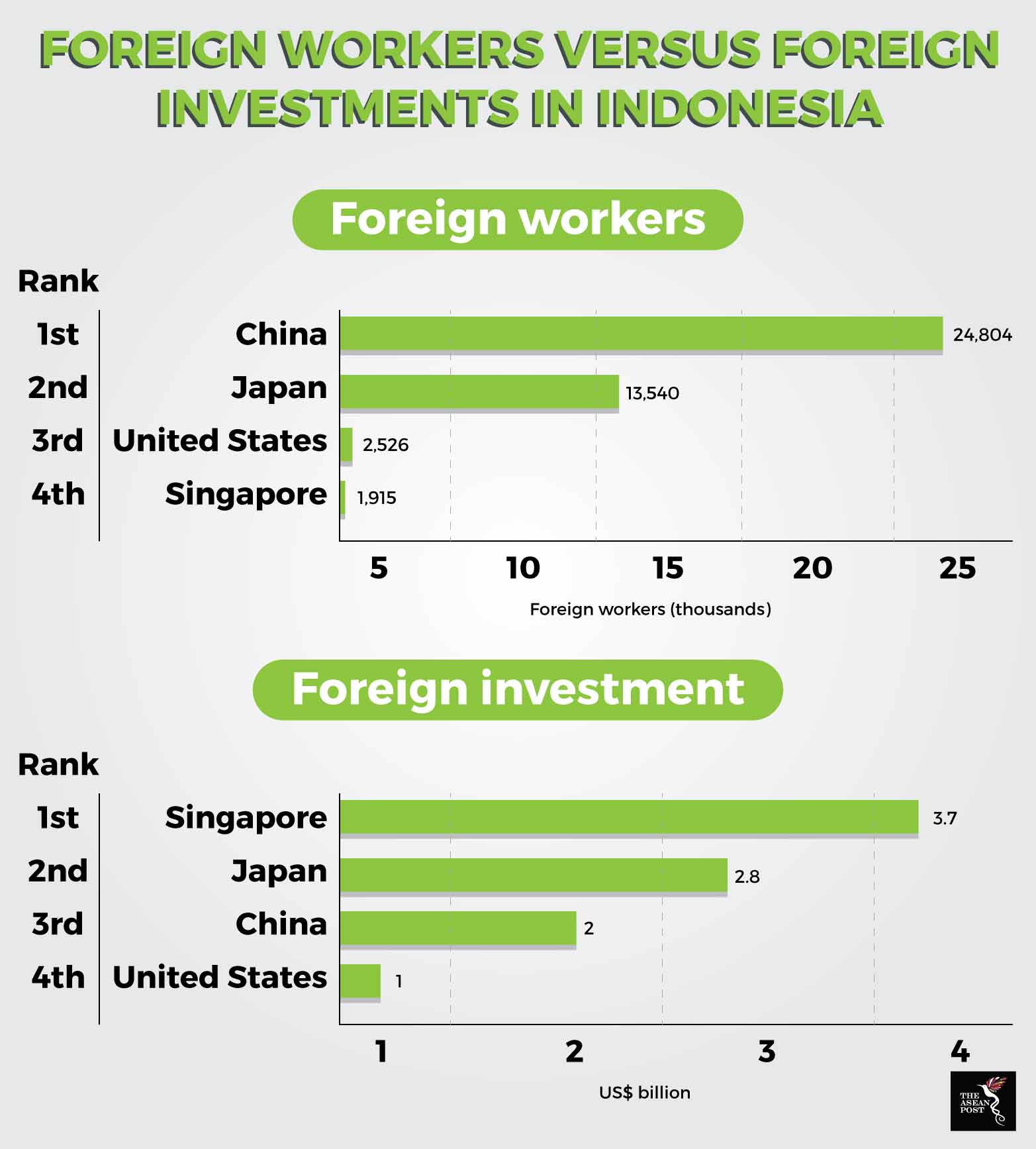

According to statistics from the Investment Coordinating Board (BKPM) as of July this year, the second quarter saw foreign direct investment (FDI) from Singapore at US$3.7 billion, US$2.8 billion from Japan, US$2 billion from China, US$1 billion from Hong Kong, and US$1 billion from the United States (US). However, the country’s Manpower Ministry shows that 24,804 foreign workers have come into the country from China, while Japanese foreign workers are almost less than half of that number at 13,540, the US has 2,526 workers and Singapore – although being Indonesia’s largest investor – has a mere 1,915 workers in the country.

Source: Various sources

In May, Indonesian tour guides from Bali marched to the immigration office protesting against a sudden increase in the number of Chinese national tour guides.

Keith Loveard, a senior analyst with Jakarta-based business risk firm Concord Consulting, said Indonesian President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo’s relationship with China was becoming an election issue.

“The relationship with China could turn toxic for him,” he said.

It is worth noting that in a previous smear campaign aimed at Jokowi during the 2014 presidential election campaign, one of the accusations hurled at Indonesia’s current president was that his grandfather was Chinese. This possibly hints at a deep resentment that some locals may harbour towards Chinese in general.

The negotiating table

When commenting on plans to scrap some Chinese projects, Djojohadikusumo dismissed concerns that Prabowo would be seen as anti-Chinese. He cited Malaysia’s case where the country’s prime minister Mahathir Mohamad had frozen US$22 billion-worth of Chinese-backed projects since he came into office following a landmark election victory.

The question is whether Djojohadikusumo’s comparison between Mahathir and his brother is applicable in the first place. While Mahathir may carry his own controversies, numerous observers have claimed he is a well-respected icon globally. And even if those claims do not carry enough weight, Mahathir, who is now serving his second term as prime minister, was a prime minister for 22 years in his previous term.

On the other hand, Prabowo was not only defeated in his attempt to become president in 2014, in 1998 he was also dishonourably discharged from the military and subsequently banned from entering the US because of his alleged record of human rights violations.

Perhaps the real question here is what would Prabowo bring to the negotiating table when attempting to scrap any of China’s infrastructure projects.

Undoubtedly, many Indonesian voters – like the rest of their ASEAN peers - would like to see as little Chinafication on their home soil as possible. But while the promise to scrap Chinese funded projects could win Prabowo some votes, it would be wise for voters there to question whether or not this is something the presidential candidate could pull off in the first place.

Related articles:

The making of new Chinese colonies