Talks about the “Quad” – a four-way security dialogue between the US, India, Japan and Australia – has resurged since it was first championed by Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe in 2007. This time, it centred around the notion of a “free and open Indo-Pacific.”

What the term, “Indo-Pacific” popularised by US President Donald Trump during his visit to Asia entails is still not set in stone. But it has raised the eyebrows of Beijing which warned against exclusionary regional cooperation in the region.

According to Senior Fellow of the ISEAS-Yusuf Ishak Institute, Malcolm Cook when contacted by The ASEAN Post “the “Quad” is an important development and clearly focussed on dissuading Chinese aggressive actions.”

Shifting regional orders

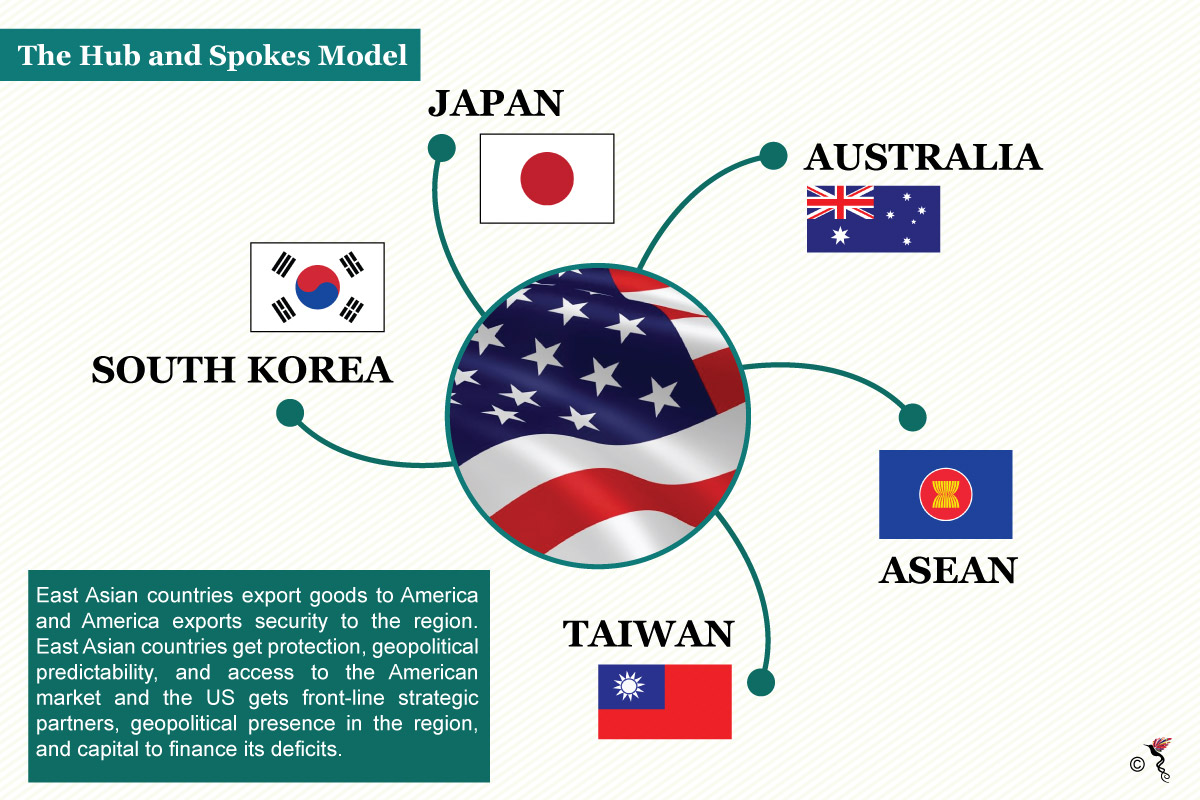

The geopolitical reality of the region has shifted and the postwar “hub and spokes” model where the US provides a security guarantee for East Asian states in return for regional clout is fast changing shape. What accompanied the barter was also an economic relationship where the US allowed market access for countries in the region – which saw the meteoric economic rise of the “Asian Tigers” like Japan and South Korea – is also seeing a similar shift.

A visualisation of the hub and spokes relationship.

That economic relationship is now being challenged by China which is has become an important economic partner of many countries in this region.

China’s share of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) into ASEAN increased to 6.8% in 2015 from 5.1% in 2013 whereas US share has flatlined since 2014. Besides that, China also has a bigger share of total trade with ASEAN compared to the US and its overall share of total ASEAN trade in 2015 is second only to the total share of intra-ASEAN trade.

Moreover, China has made inroads in the region via the Belt Road Initiative (BRI), which, according to Credit Suisse, could see Beijing investing upwards of 500 billion dollars in 62 projects over the next five years. So far, there have been several infrastructure projects currently scheduled or being developed in Thailand, Lao, Singapore, Malaysia and Cambodia.

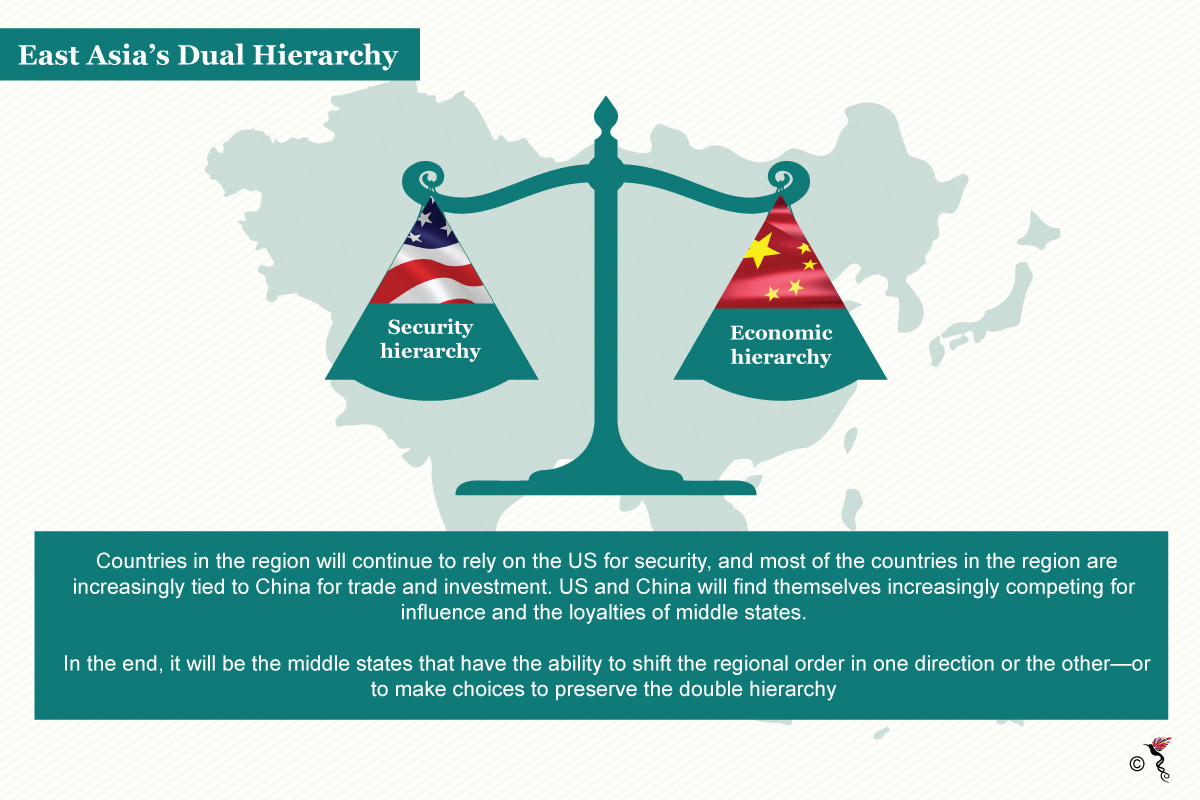

According to Professor of Politics and International Affairs in the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs at Princeton University, Gilford John Ikenberry, a regional power transition is currently underway, marked by the emergence of “duel hierarchies.” In a 2015 article published by Political Science Quarterly, Ikenberry elaborates that these two hierarchies – economic hierarchy and security hierarchy – are dominated by China and US respectively.

“The dual hierarchical order does create and reinforce competitive dynamics between the two lead states. There are increasingly two states offering hegemonic leadership within the region. As a result, the United States and China will find themselves increasingly competing for influence,” he wrote.

A visualisation of the East Asia Duel Hierarchy

Dealing with the “Quad”

China has every reason to be mindful of efforts to contain its rise although the US denies that the "Quad" is specifically designed to contain China. Obama’s “Pivot to Asia” and the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) were clear measures of containment. But to Beijing’s relief, Trump’s election and subsequent US rescindment of the TPP was a renewed opportunity for China to repair the damage done by the “pivot.”

However, despite Trump’s apparent obsession with undoing his predecessor’s policies, it has become increasingly clear that his attitude towards this region hasn’t changed much from Obama’s. Trump still wants to engage with the region and given recent developments with regards to the “Quad” it seems like he very much wants to retain East Asia within the American orbit.

According to Senior Fellow at the Rajaratnam School of International Studies, Sinderpal Singh, Chinese reaction has been relatively mild, but Beijing will be keeping an extremely close eye on developments vis-à-vis the “Quad.”

“China will be confident that its economic might will serve as a significant restraint on all four countries to differing degrees. Australia is highly dependent on China for its economic well-being, as is the US to a relatively lesser level. India and Japan will also understand the economic risks to their countries in the event of heightened tensions with China,” he added in an email response to The ASEAN Post.

The seemingly imminent clash of interests between China and the US in this region will undoubtedly affect the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and its centrality within the geopolitical chess game. One of ASEAN’s fundamental roles as a regional organisation is to be a manager of bigger powers, so that the region doesn’t become a theatre of competition amongst major powers. However, the shifting geopolitical tectonics calls into question, ASEAN’s ability to play “manager” and ensure peace and cooperation in the region.

How ASEAN deals with this conundrum will determine its survivability in the long-term.

Recommended stories: