Ever since the military-backed government of Myanmar embarked on a series of political reforms back in 2011, the country’s political landscape has never been the same.

The political reforms carried out by Myanmar’s then government included the release of pro-democracy leader Aung San Suu Kyi from house arrest, the establishment of the National Human Rights Commission, general amnesties for more than 200 political prisoners and many others. The culmination of such reforms was seen in 2015 when the country held its first openly contested elections since 1990. There were also general elections held in 2010, however that election was widely discredited as fraudulent.

The 2015 elections saw the National League for Democracy (NLD) party led by Aung San Suu Kyi obtain a landslide victory, paving the way for the country’s first non-military president in 15 years.

At the time when Aung San Suu Kyi was elected, the political landscape was completely different. Large segments of the population were unhappy living under the authoritarian rule of the military junta. The junta was notorious for its various human rights abuses and refusal to be held accountable. The military junta was also responsible for fuelling the many ethnic conflicts that has plagued the country’s history since.

Therefore in 2015, it was only natural that the party historically known for espousing its opposition to Myanmar’s military rule while fighting for democratic rights was elected into power.

Fast forward to 2018 and the current NLD led government is already at the halfway mark of its first term in power. The current government has received widespread criticisms for its failure to deal with widespread ethnic tensions across the country. Recently, a fact-finding mission carried out by the United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHCR) found that there were patterns of gross human rights violations and abuses committed in Kachin, Rakhine and Shan states. The report also explicitly said that crimes against humanity perpetrated by the Tatmadaw in the Rakhine state were of “genocidal intent” and called out state councillor and Nobel Prize winner Aung San Suu Kyi. She was criticised for not using her “de facto position as Head of Government, nor her moral authority, to stem or prevent the unfolding events, or seek alternative avenues to meet a responsibility to protect the civilian population”.

The government has since denounced the findings of the mission.

Source: Various

Source: Various

New political parties

The NLD’s failure to enact meaningful reforms to alleviate ethnic tensions has led experts to predict that new political formations built along racial and religious lines will mushroom in the country. Many of these new parties are expected to take part in the upcoming 2020 general elections.

Ethnic based political parties are not a new concept in Myanmar. They are actually widespread, as the ethnic divisions in Myanmar have caused many ethnicities to form political parties to fight for their own rights and for autonomy over their own region in some cases. In fact, many of the ethnic political parties ran in the previous elections too but did not win many seats. Aung Aung, a Visiting Fellow in the Myanmar Studies Programme of the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute, wrote that many ethnic leaders voted for the NLD instead of ethnic political parties because “the ethnic people hoped that the NLD would bring effective change such as constitutional amendments and allow them to realize their dream of a genuine federal union.”

Last month, three parties in the Chin region, the Chin National Democratic Party (CNDP), the Chin Progressive Party (CPP) and the Chin National League for Democracy merged to form the Chin League for Democracy Party (CLD). According to Salai Cieu Bik Thawng, secretary of the CNDP, the merger is to give the Chin people a unified voice in national politics.

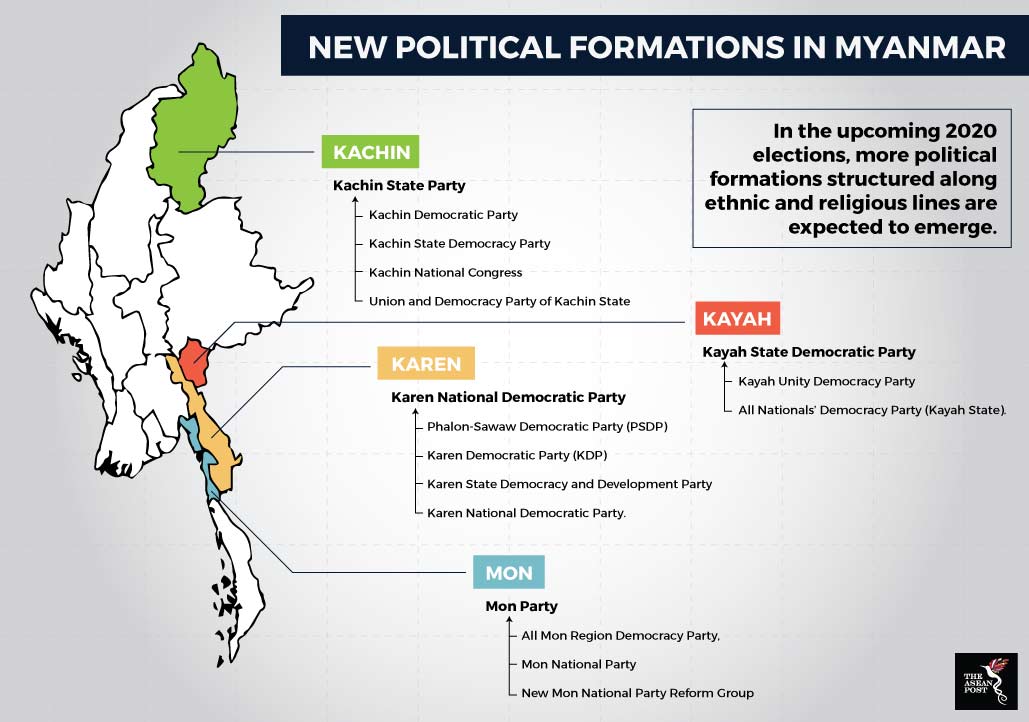

Mergers like this have become commonplace as ethnic political parties look to become more unified and increase their chances in the upcoming general elections. In 2017, two Kayah parties in Kayah State merged, while this year saw four Karen parties in Karen State merge. Aside from that, three Mon parties in Mon State and four Kachin parties have also agreed to merge.

As shown in 2015, the elections are a legitimate way to power and to enact policies in Myanmar. There is a strong possibility that more parties will emerge to contest in the upcoming general elections. The NLD should be wary and look to carry out the promises it made during the 2015 campaign should it wish to obtain another landslide victory in 2020.

Related articles:

Myanmar crisis getting out of hand