When credit card details are hacked, banks can easily cancel the accounts and replace the cards. The same cannot be said with stolen medical records. A person’s family history, insurance, prescribed medications and so forth cannot be changed.

A data breach at Singapore’s largest healthcare group, SingHealth, compromised the demographic data of 1.5 million patients, including 160,000 dispensed medicine records.

Hackers infected a front-end workstation with malware and gained access to SingHealth’s database. Between 27 June and 4 July, they exfiltrated data of patients who visited SingHealth’s specialist outpatient clinics and polyclinics from 1 May 2015 to 4 July 2018.

The Singapore government stressed that no medical records were tampered with and no diagnoses, test results or doctors’ notes were taken. The only information lost were personal profiles – names, addresses, gender, race, date of birth and national registry numbers.

Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong tried to play down the incident in a Facebook posting, saying the cyber-attackers “would have been disappointed” if they were looking to embarrass him. "My medication data is not something I would ordinarily tell people about, but there is nothing alarming in it," he said.

The hackers specifically and repeatedly targeted Lee’s personal particulars and his outpatient dispensed medicines. Lee is a two-time cancer survivor and any news that suggest deteriorating health may likely cause shockwaves in Singapore as no successor has yet been named to replace the 66-year-old premier.

Well-planned attack

Singapore’s Cyber Security Agency (CSA) and the Integrated Health Information System (IHiS) said the cyberattack was “deliberate, targeted and well-planned” and “not the work of casual hackers or criminal gangs.”

The cyberattack was “very different” from actors who usually sell the stolen data or use them for ransom, said Eric Hoh, Asia Pacific president of cybersecurity firm, FireEye. To date, the stolen data have not appeared for sale on the dark web.

This led most security experts to speculate that a “well-resourced, well-funded and highly sophisticated” nation-state actor was behind the attack. “Furthermore, the attackers continued trying to access SingHealth’s network even after detection, which is a typical signature of a nation-state actor,” Hoh said.

However, it is difficult to attribute malware and cyberattacks, said Nick FitzGerald, senior research fellow at ESET.

Attacks are grouped into clusters of Advanced Persistent Threat (APT) based on similarities in their techniques, attack patterns, code and infrastructure. Some groups may appear to be especially prolific and well-provisioned. They may be state-sponsored or a very large and well-funded cybercriminal operation, he said.

The targeted search for records relating to the prime minister and other ministers suggests a political element but it could equally have been a group external or internal to Singapore. “If it is the latter, it could be a group with a more mainstream political agenda, or perhaps ‘hacktivists’ wishing to make a point,” he said.

“The government’s claim of a state-sponsored actor cannot be ignored but given the short period of time since the attack was first noticed, it is unclear to me that enough effort was assigned to the forensic analysis to be certain it was,” he said.

The CSA is said to have narrowed the sources to a few countries known to have the level of sophistication to conduct the attack but declined to reveal further details due to “operational security reasons.”

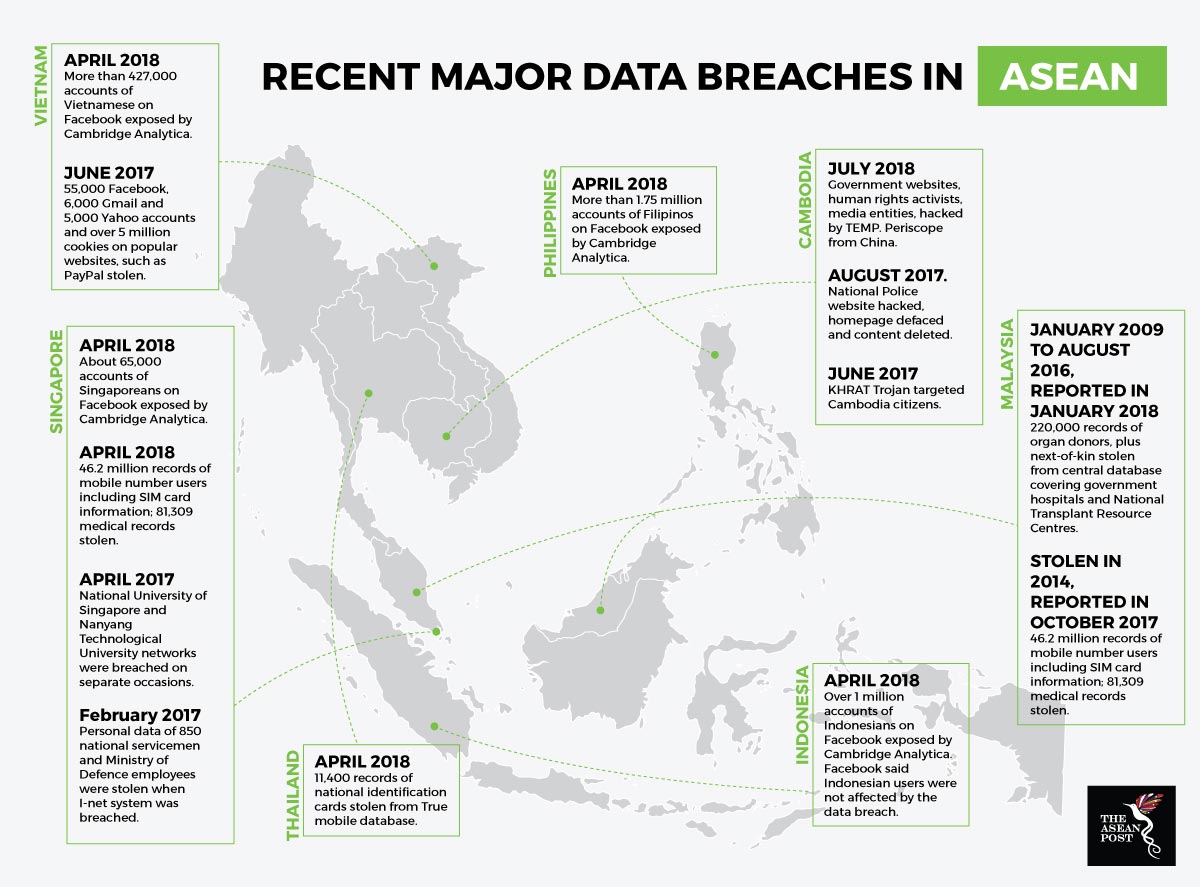

Source: Various sources

Source: Various sources

Devastating consequences

Stolen medical records can have devastating and far-reaching consequences. Criminals can create fake identities to buy and resell medical equipment or drugs. An impostor may undergo treatment for different conditions and result in changes to a victim’s records. This could lead to misdiagnoses and wrong prescriptions for the actual victim.

Cybercriminals can call the victims and attempt to sell them useless equipment or drugs under the pretext of knowing their medical history. Families of victims can be scammed into paying out large sums of money using their medical history.

Stolen medical data can be combined with a false provider number to make fraudulent insurance claims. Criminals can max out the claims, leaving their victims without adequate coverage when needed. Medical identity thefts are one of the causes of medical premium hikes.

Hackers may also demand a ransom from clinics and hospitals to keep the matter quiet and not sell the stolen records on the dark web, where they can be worth as much as US$408 each according to a 2017 study by Ponemone. The Singapore government’s disclosure effectively thwarted any such attempts.

SingHealth faces the possibility of lawsuits, fines and a loss of public confidence. “Individuals whose data were accessed can do very little,” said FitzGerald. “This is pretty much a worst-case scenario as the breach is really a breach of trust: they entrusted their digital medical records to SingHealth. It was solely SingHealth’s responsibility to maintain the confidentiality of that data and it appears to have failed in that responsibility.”

Nonetheless, all SingHealth patients should check through official channels to see if their data were stolen. They need to be extra vigilant when receiving phone calls or email from unknown sources claiming to be from legitimate organisations.

Regaining the public’s trust may be the government’s biggest challenge, given the scale of the breach. The attack raised doubts on Singapore’s Smart Nation Initiative, launched in 2014 to integrate various technologies such as medtech, fintech and govtech to create a digital smart city-state.

“The government has to perform a full and thorough forensic examination of the affected systems and determine the scale of shortcomings and failings that led to this data breach. Depending on the outcome, other Smart Nation initiatives may have to be reconsidered,” said FitzGerald.

A Committee of Inquiry (COI) chaired by retired district judge Richard Magnus will be convened to conduct an independent external review of the incident. All Smart Nation plans have been paused, especially mandatory contribution to the National Electronic Health Record (NEHR) project that lets hospitals share patient data.

Lee insisted that the Smart Nation will continue despite this incident. “We cannot go back to paper records and files. We have to go forward to build a secure and Smart Nation,” he posted on Facebook.