Recent reports that China’s military and naval facilities are nearing completion have not fazed the Philippines, who have not taken any form of military action to halt the further progress of China into the waters of the South China Sea (SCS).

According to reporting by the Philippine Daily Inquirer, three of the seven islands, namely Mischief, Fiery Cross and Subi now have completed Chinese runways while there are also lighthouses, hangars and wind turbines on the remaining four islands, namely McKennan, Calderon, Burgos and Johnson South.

“We expect that China, being not just a member of the United Nations but also a permanent member of the Security Council, will adhere to the prohibition on the use of force,” said Harry Roque, spokesman for Philippine President, Rodrigo Duterte.

He said there was nothing the Philippines could add to the previous Benigno Aquino III administration’s inability to act on China’s reclamation of the land that now forms these islands.

Territorial disputes: who defines the laws?

The Philippines may have little reason to fear Chinese militarism because it has strong economic ties with China. China has also pledged loans and investments of up to US$24 billion in the Philippines’ Build-Build-Build infrastructure program and telecommunications industry, among other shared interests, according to reporting by the Philippine Star.

A 2016 arbitration award in the Philippines’ favour by the International Court of Justice (ICJ) was not enforced by the Philippines with President Rodrigo Duterte appearing to overlook it.

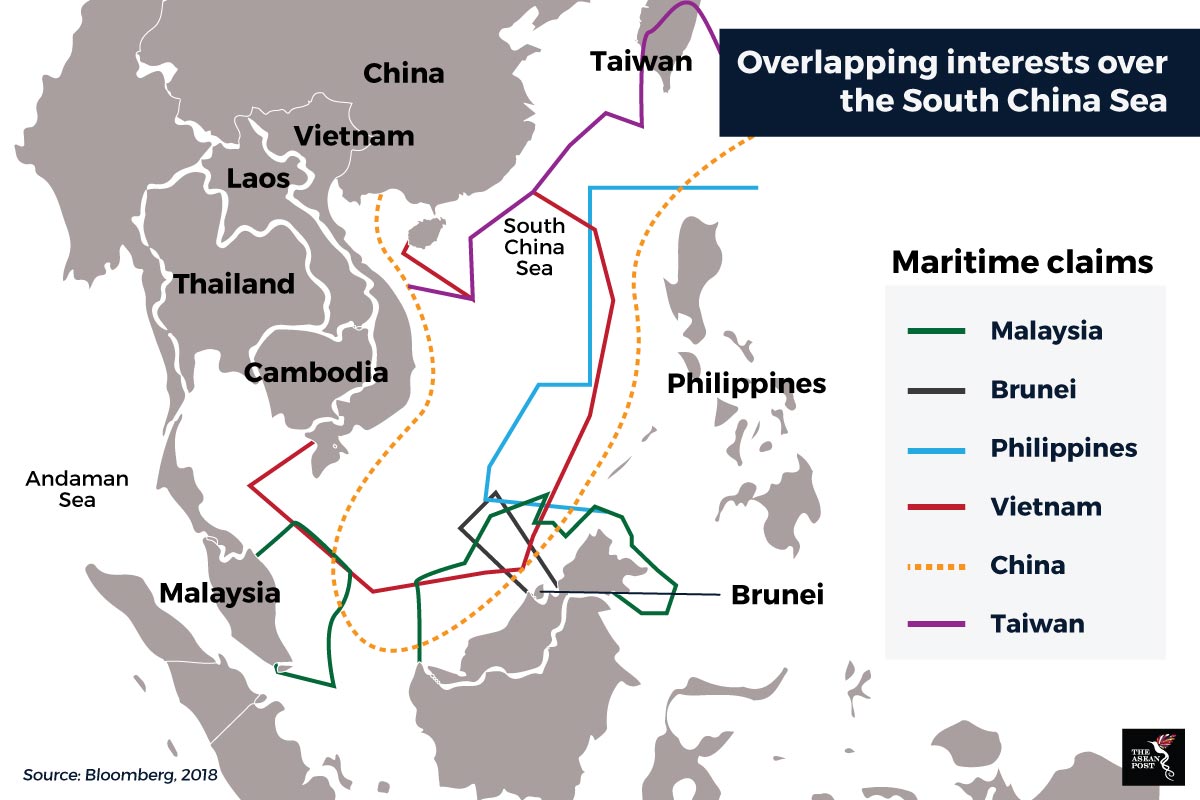

Although there exists concurrent, overlapping claims by Brunei, Taiwan and Malaysia on the South China Sea islands, China is also cultivating relationships with these nations, which reduces the likelihood that they will protest China’s territorial claims over the SCS very strongly.

Cambodia, for one, signed 19 investment and aid bilateral agreements with China in January 2018 to develop key sectors like infrastructure, healthcare and agriculture, according to reporting by Reuters.

Meanwhile, Indonesia in 2017 received US$5.5 billion in combined foreign direct investments from China and Hong Kong, most of which were for electricity, construction and power plants, according to reporting by the Nikkei Asian Review.

Vietnam, however, is caught midway between the United States and China. It recently received a backlash from China for inviting India to invest in the oil & gas sector in the SCS, according to the Economic Times of India. According to the same report, China has objected to exploration of oil wells in the SCS by India’s Oil & Natural Gas Corporation (ONGC) to explore oil wells for years, with China alleging that such activity would constitute an infringement upon its territorial rights.

Should China militarise in the Southeast Asian region, ASEAN nations will most likely only be able to rely on the customary international law on the use of force. The ICJ defines customary international law as “…evidence of general practice accepted as law.” Countries normally fall back on this aspect of international law in the absence of treaties or conventions defining specific obligations between countries.

“ASEAN will most likely negotiate the Code of Conduct for the South China Sea (CoC) with China in March 2018”, said Chandra Yudha, ASEAN political and security cooperation director at Indonesia’s Foreign Ministry at a press conference in Jakarta recently.

Mark J Valencia, adjunct senior scholar with the National Institute for South China Sea Studies in China notes that complete agreement by all ASEAN countries is “highly unlikely” due to ASEAN’s divided loyalties between China and the United States.

The CoC will also likely be powerless to resolve the territorial dispute. The Max Planck Encyclopaedia of Public International Law states that codes of conduct in the context of international law are defined as “…regulatory instruments consisting of written sets of rules and principles which can deal with very specific or more general areas of regulatory concern.”

Meanwhile, an early draft of the CoC described the document as “…a set of norms to guide the conduct of parties and promote maritime cooperation in the South China Sea,” according to analysis done by the ISEAS Yusof Ishak Institute August 2017. It also does not contain the phrase “legally binding”, according to an analysis report titled, ‘Assessing the ASEAN-China Framework for the Code of Conduct for the South China Sea’.

Another matter the draft CoC is also silent about is enforcement measures and dispute resolution mechanisms such as arbitration.

In general, basic undertakings by each country are divided into six parts, including a provision for ‘self-restraint/prevention of incidents’. While the provision for ‘prevention of incidents’ is new, the DoC, which precedes the CoC did not previously define the meaning of ‘self-restraint’. According to the ISEAS Yusof Ishak Institute report, this resulted in various parties interpreting the clause as they saw fit. For example, Reuters reported in 2017 that China had threatened military action against Vietnam if they did not half oil drilling operations in the disputed SCS region.

Meanwhile, the draft CoC also provides for adherence by all parties to the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) which essentially points ASEAN back to customary international law. Enforcement mechanisms include the possibility of appointing an arbitration tribunal, referring the matter to the ICJ or to the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea.

In light of prevailing economic and political interests, ASEAN countries are most likely to follow the Philippines’ example. This could mean overlooking a ruling in their favour even if it is handed to them.

Based on these assessments, international law is not likely to provide a legal recourse for the territorial dispute between China and ASEAN on the South China Sea. Yet as long as each ASEAN country continues to engage and share common interests with China, soft security is likely to be the only defence against any possible activation of China’s military force in the region.

Recommended stories: