You can boil it, bake it, deep fry it, stir fry it, cook it in a curry, and now the Cambodians are going to make an industry out of it. Traditionally a net importer of potato, amounting to around 5,000 tonnes every year from Thailand, Vietnam, China, Japan, Australia and the United States (US), Cambodia is eyeing not only the future local potato market, but also the regional one.

Potato consumption in Cambodia has been on an upward trajectory in the kingdom, both driven by consumption by locals as well as tourists. The increasing demand was so significant that the Agricultural Ministry invested in a US$200,000 potato research and development (R&D) centre parked under the Royal University of Agriculture in Phnom Penh in 2016.

The R&D centre - built in collaboration with the Korean Project of International Agriculture (KOPIA), the Korean International Cooperation Agency (KOICA), and the Ministry of Rural Development - has been tasked to find the right potato varieties most suited to the country and grow the industry to fill the demand. For this purpose, 17 varieties were brought in from Thailand, Vietnam, Germany and Ireland, including potato of the Tornado, Madeira, Concordia, Julinka, Jelly, Electra and Fandango varieties for trial planting. The Cambodian Potato Research Centre has also been elbow-deep in finding the right areas to develop as potato farming hubs.

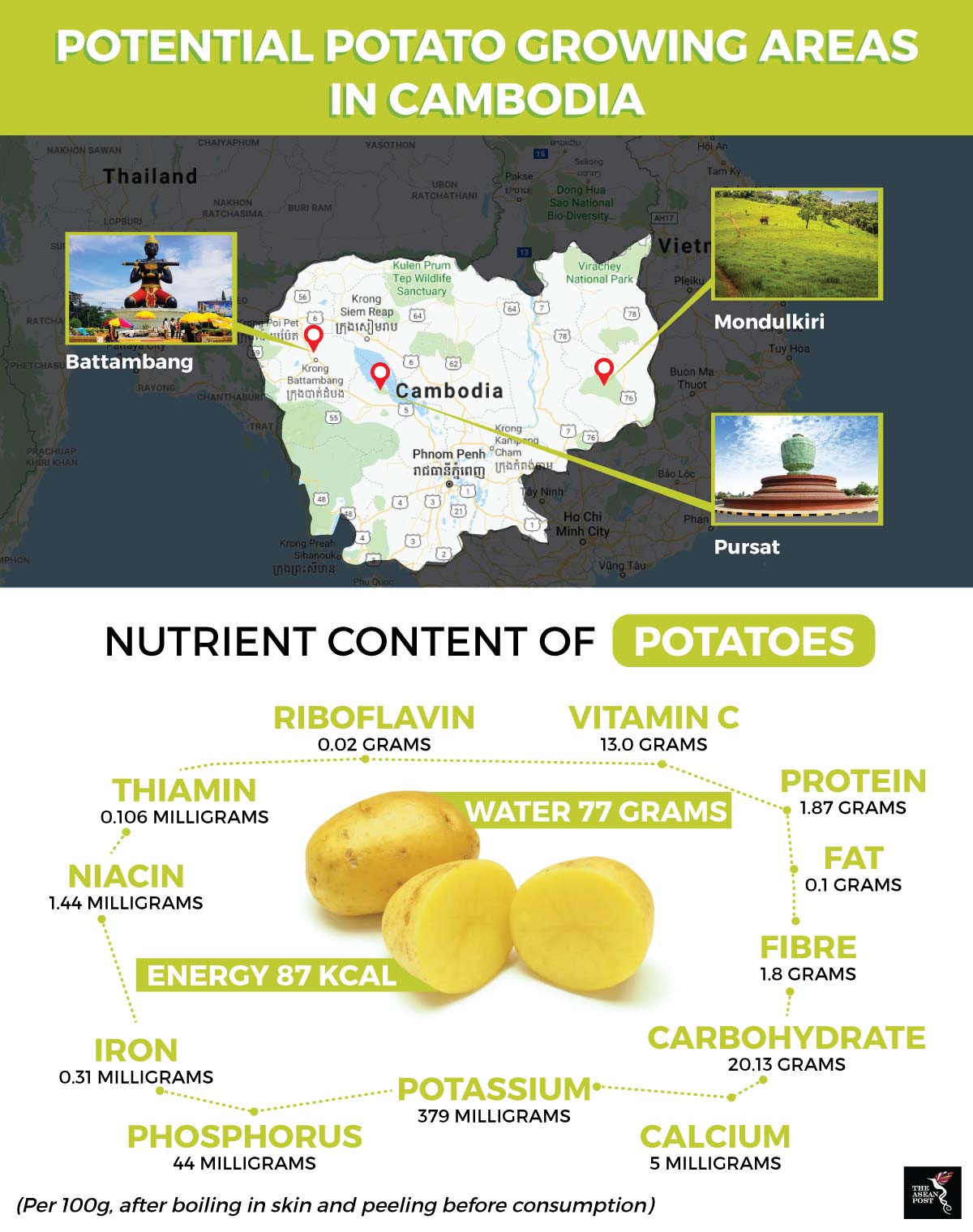

The results have been encouraging. In April this year, the centre announced the selection of six areas for potato crop planting trials, namely the capital itself, and the provinces of Kampong Chhang, Tboung Khmum, Battambang, Pursat and Mondulkiri. The last three areas have been found to be the most suitable, having the right soil and climate conditions for potato growing. The two-year trials have also shown that certified seed of good quality is crucial for crop success. However, according to Song Kheang, Mondulkiri’s Provincial Agriculture Department Director, one last round of testing is still needed before results can be finalised.

“We are still conducting tests. We have another round of tests before we can claim that the province is suitable for farming potatoes. After three initial testing phases, we can say the soil in the province is suitable for potatoes, but there are still some problems, so we need to keep testing,” he said to local media.

Traditionally, potato farming is neglected in Cambodia due to the availability of imported potato from neighbouring countries, as well as a lack of awareness on potential markets, education on correct growing techniques, and understanding the growing climate.

There are over 4,000 edible varieties of potato, mostly found in the Andes of South America. In terms of impact on human food security, potato is the third most important food crop in the world after rice and wheat. Potatoes are nutrient rich food and are an excellent source of carbohydrate as it is low in fat. 100 grams of potato boiled with the skin on and peeled before consumption provides 20.13 grams of carbohydrate, 1.87 grams of protein, 1.8 grams of fibre, 100 milligrams of fat, 379 milligrams of potassium, 44 milligrams of phosphorus, 13 milligrams of Vitamin C, five milligrams of calcium, 1.44 milligrams of Niacin, 0.31 milligrams of Iron, 0.106 milligrams of Thiamin, and 0.02 milligrams of Riboflavin.

Source: Various

Source: Various

Cambodia has achieved remarkable results in poverty eradication, with the poverty rate decreasing from 47.8 percent in 2007 to 14 percent in 2016. However, a significant portion of the population remains vulnerable to shocks, such as disaster and climate-related events, that could push them back into hardship. Over 80 percent of the population there live in the countryside and agriculture remains the predominant economic activity for 42 percent of its working men and women. Undernutrition remains a public health concern, with 32 percent of children under five years of age suffering from stunting, 24 percent are underweight, and 10 percent wasted. Micronutrient deficiencies are also widespread.

According to the latest study conducted by the World Food Programme (WFP), Cambodia needs around one million tons of vegetable annually, around 56 percent or approximately 510,000 tons of which are imported annually from neighbouring countries. It spends over US$200 million for imported vegetable to meet local demand.