One of the 17 targets of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) include Zero Hunger, which is Goal 2 after Goal 1: No Poverty. The SDGs, also known as Global Goals were adopted in 2015 as a call to end poverty, protect the planet and ensure that all people enjoy peace and prosperity by 2030.

Unfortunately, the world is not on track to achieve Zero Hunger by 2030. The problem is now even further exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic.

According to the “State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World” report published last July by the United Nations (UN), it is estimated that nearly 690 million people went hungry in 2019, or 8.9 percent of the world’s population. This is an increase of 10 million from 2018, and 60 million in five years. However, the report forecasts that the pandemic could tip over 130 million more people into chronic hunger by the end of 2020.

Moreover, COVID-19 has increased food security risks in some parts of the world such as in the Asia-Pacific as strict quarantine measures and export bans on basic food items have affected all stages of food supply.

For example, in Cambodia, where there’s wide-spread poverty, consumers have been hit hard by lack of food supplies, a rise in prices of staple foods and also a halt of income due to the crisis. In April, Cambodia’s premier Hun Sen even announced that the country will halt rice exports to protect food security during the COVID-19 outbreak.

An article published by non-profit organisation, OneWorld Foundation last June titled, “Cambodia’s Food Insecurity Rises Due to COVID-19” states that “despite the government working towards ensuring a continuous operation of supply chains, food security is affected by lack of safety income-net for these Mekong delta inhabitants who are at the mercy of natural events and weather.”

The United Nations International Children's Emergency Fund (UNICEF) has also warned that in the absence of timely action, the number of wasted children under-five could increase globally by about 15 percent this year due to COVID-19.

“COVID-19 has hit vulnerable families the hardest,” said Debora Comini, a UNICEF Representative. “Unless we urgently scale up prevention and treatment services for malnourished children, we risk seeing an increase in child illness and deaths linked to malnutrition.”

ASEAN member state Indonesia is already facing high levels of malnutrition. According to UNICEF, more than two million children in the country suffer from severe wasting, a condition characterised by low weight for height, and more than seven million children under-five are stunted. Indonesia is one of the countries hardest-hit by the COVID-19 virus in Southeast Asia. Overburdened health facilities, disrupted food supply chains and income loss due to the pandemic could lead to a sharp rise in the number of malnourished children in the archipelago stated UNICEF.

Death From Hunger

The UN World Food Programme (WFP) said seven million people have died of hunger as of October this year and the pandemic could double world hunger.

In an urgent call in July from the UN, the organisation said that COVID-19-linked hunger is leading to the deaths of 10,000 more children per month over the first year of the pandemic. Based on a worst-case scenario by the UN, nearly 180,000 children could die this year alone. In addition, the pandemic could also lead to young children missing 50 percent of their nutritional care and treatment services.

Hunger Index

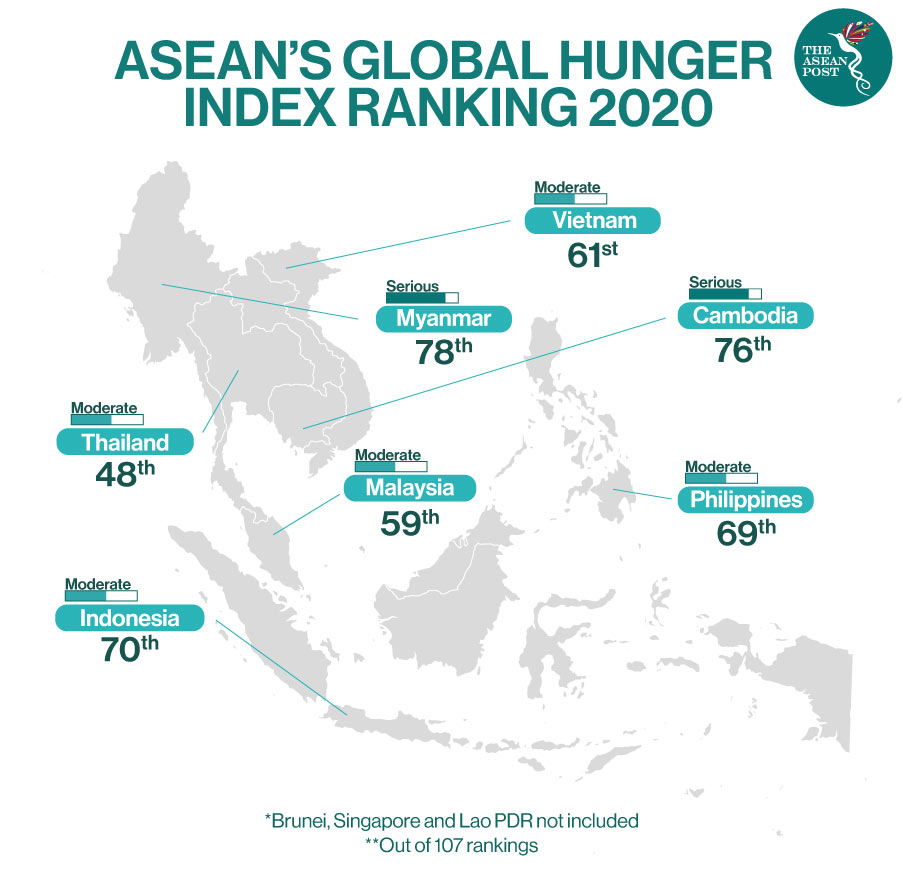

Worldwide hunger and undernutrition, when calculated as a global average, can be classified as moderate. However, different countries face different challenges and situations on a yearly basis. According to the recently released Global Hunger Index (GHI) 2020, three countries surveyed have “alarming” levels of hunger (Madagascar, Timor-Leste, Chad), while more than 30 countries have “serious” levels of hunger based on the GHI Severity Scale. ASEAN member states Myanmar and Cambodia fall in this category.

Despite the aforementioned Southeast Asian countries’ “serious” levels of hunger, they have actually made significant improvement over the years. Both ASEAN member states were classified as having “alarming” levels back in 2000.

Vietnam, the Philippines and Indonesia have also made progress over the years in terms of combatting hunger as all three countries had “serious” levels of hunger a few years ago, but are now deemed “moderate.”

While some countries have made achievements and numerous efforts in reducing chronic hunger and poverty, the pandemic may cause setbacks, hampering some countries’ ability to make progress toward meeting the SDGs.

Related Articles: