Recently, students from secondary schools and the National University of Laos met in Vientiane to learn about human trafficking and, especially, how to counter trafficking in persons under the rule of international law. The topic was discussed during the course of a Model United Nations (UN) event, which took place at the UN House in Vientiane.

According to a statement from the Asian Law Students’ Association Laos, the main purpose of the session was to broaden the students’ understanding about anti-human trafficking.

This came soon after the world witnessed the World Day against Trafficking in Persons 2019 on 30 July recently. The World Day against Trafficking in Persons is especially pertinent to this part of the world.

According to the Global Report on Trafficking in Persons 2016, published by the UN Office on Drugs and Crimes (UNODC), more than 85 percent of victims were trafficked from within the region. The Walk Free Foundation’s Global Slavery Index 2016 states that within Southeast Asia, Thailand is the leading destination for trafficked victims from Cambodia, Lao, and Myanmar.

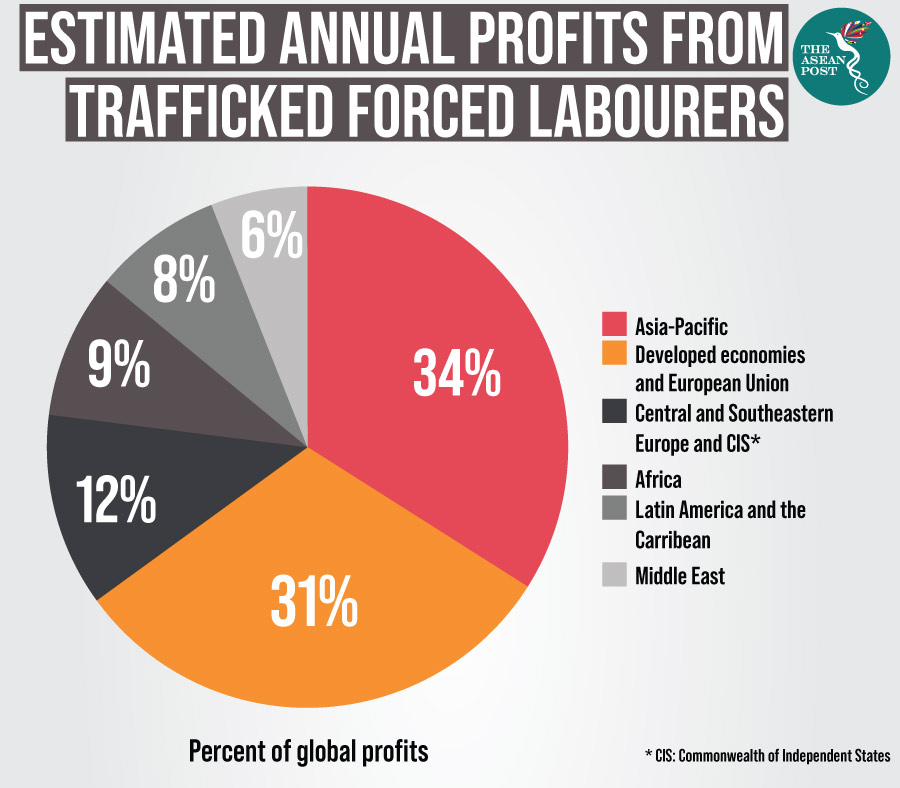

Southeast Asia is making human traffickers a lot of money. According to some estimates, human trafficking is now one of the world’s most lucrative organised crimes, generating more than US$150 billion a year. Meanwhile, the Walk Free Foundation’s Global Slavery Index notes that two-thirds of victims, or 25 million people, are from East Asia and the Pacific.

In an attempt to explain some of the reasons behind human trafficking in Southeast Asia, the United States (US) Department of State’s Trafficking in Persons Report 2018 quotes the International Organization for Migration (IOM) as noting that many Southeast Asian victims migrate in search of paid jobs but wind up forced to labour in fishing, agriculture, construction, and domestic work. Most of them are men who cannot repay exorbitant fees charged by unauthorised brokers and recruiters and so become vulnerable to debt bondage and other forms of exploitation.

Lao government efforts

Placing Lao under the Tier 2 Watch List, the US Department of State notes that Lao is more of a source country and only to a lesser extent a destination country. In some ways, knowing that it is Laotians being taken from their homes to end up in the sex trade or forced labour makes combating human trafficking in Lao all the more important.

“Traffickers exploit a large number of Lao victims, particularly women and girls, in Thailand in commercial sex and in forced labour in domestic service, factories, or agriculture. Traffickers exploit Lao men and boys in forced labour in Thailand’s fishing, construction, and agricultural industries. Some women and girls from Lao are sold as brides in China and subjected to sex trafficking or forced domestic servitude. Some local officials reportedly contribute to trafficking vulnerabilities by accepting payments to facilitate the immigration of girls to China,” the Department of State notes.

The Lao government, however, has not been sitting on its hands on this front. In July 2018, Lao Prime Minister Thongloun Sisoulith issued a decree mandating the creation of multi-sectoral anti-trafficking steering committees at the provincial and district levels to implement the 2016 Anti-Trafficking Law and National Action Plan.

Following the decree, the government of Lao supported awareness campaigns and workshops to support sub-national jurisdictions to form their own anti-trafficking commissions. In an effort to implement the National Action Plan, the Ministry of Labor and Social Welfare (MLSW) and the Lao Women’s Union (LWU) held awareness-raising workshops on safe migration and the protection of victims of trafficking throughout the country, reaching 1,080 people.

Trainings targeted district officials, public security, the labour and social welfare departments, the LWU, school administrators, and youth unions. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MOFA) also held trainings to increase the understanding of regional and international conventions on transnational crime, including human trafficking, with a total of 352 participants. Meanwhile, the Ministry of Education and Sports hosted awareness-raising seminars on human trafficking targeting education and sports administrators throughout the year, reaching 3,710 participants.

Despite the efforts, more needs to be done to address human trafficking in Lao. Among some of the efforts that the Lao government needs to look at is addressing corruption. The US Department of State also noted on its trafficking profile of Lao that an increasing number of Chinese- and Vietnamese-owned companies reportedly facilitate the unregistered entry of labour migrants from their respective countries into Lao – with possible assistance from corrupt Lao immigration officials.

“With insufficient oversight by local authorities, these workers are vulnerable to forced labour in mines, hydropower plants, and agricultural plantations,” it said.

Considering the fact that Lao is one of the main destination countries for human trafficking, addressing it at home may also have a positive effect on neighbouring countries relying on Lao’s trafficked victims. It is hoped that with help from all relevant parties and based on recommendations including those from the US Department of State, Lao will be able to improve its score by next year.

Related articles: