The last time Aung San Suu Kyi visited Rakhine State in northern Myanmar was in 2015 during the country’s landmark general elections. Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy (NLD) party won by a landslide victory – ending military rule of the country and ushering in a new civilian government. The Nobel Peace Prize laureate was heralded as the leader who would turn around the struggling democracy.

Her next visit was in early November this year. From her last visit till now, her name has been dragged through the mud by the international community because of her apparent inaction towards the humanitarian crisis unfolding near the Myanmar-Bangladesh border. The exodus of Rakhine Muslims, also known as Rohingyas has put the fledgling democracy on the map for all the wrong reasons.

After violence broke out in late August when Rohingya militants attacked Myanmar border posts, the Myanmar military (Tatmadaw) fought back. However, their tactics were downright brutal with Amnesty International calling it a “campaign of violence that has been systematic, organized and ruthless.”

“The current situation in Myanmar is a humanitarian crisis rooted in a long-standing political impasse in which the Myanmar authorities do not recognise the Rohingya as citizens of their country,” Champa Patel, Head of Asia at Chatham House told The ASEAN Post in an email response.

The Rohingya or Rakhine Muslims are perceived as outsiders of Bengali origin hence aren’t officially recognised by the Myanmar government. By virtue of calling them “Rohingya” it connotes that there is some form of recognition towards their ethnicity, which is why the government steers clear from using that term – preferring instead to call them by the politically correct term, “Rakhine Muslim.”

Suu Kyi’s delayed response to the Tatmadaw’s assault invited criticism from various quarters. Others however, sympathised with her as she is just a State Counsellor – a position created so that she would be de facto head of government due to a technicality in the constitution. In her capacity as State Counsellor, she does not have control over the military who still retains a certain degree of power within the Myanmar government. Hence, the military’s actions are out of her jurisdiction and control.

According to the UN, approximately 611,000 people have fled Rakhine State since the latest spate of violence.

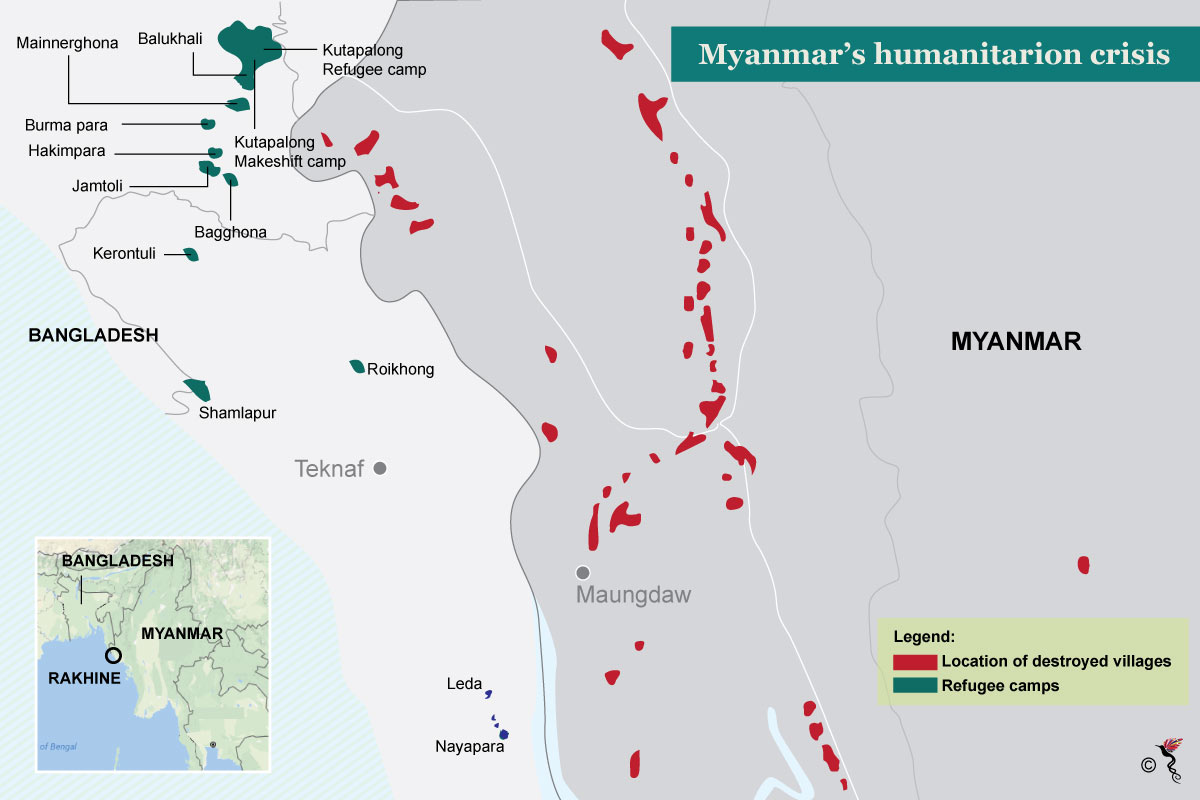

Location of refugee camps in Bangladesh

“We thought this was the only way to save our lives,” Nur Shahin, a refugee who made the deadly crossing at the Naf River near the Myanmar-Bangladesh border using plastic rafts, told Agence France-Presse (AFP).

The Rakhine Muslim population in the area – which was at 1 million previously – has severely dwindled.

“If you do the mathematics, you'll see the vast majority have actually left, which is a great concern for us,” UNHCR assistant commissioner Volker Turk was quoted as saying by AFP.

Human Rights Watch (HRW) recently published ten principles for protecting the refugees fleeing the dreadful situation in northern Myanmar. The principles called upon Naypyidaw to acknowledge the rights of these individuals as refugees and allow for them to be repatriated in a “fair, safe, and orderly manner.” HRW also called on Dhaka to keep its borders open and continue biometric registration of refugees while fully respecting the dignity and personal information confidentiality of the refugees.

On Wednesday, the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) released a formal statement expressing “grave concern” over the events transpiring in Rakhine State – which was rebuffed by the Myanmar government. Vis-à-vis the statement, the devil lies in the details as it would have been more impactful for the UNSC to pass a resolution on the matter. However, such a move was blocked by China – which holds a veto in the council and is an influential backer of the Myanmar military junta.

The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) has also been sluggish to react to the situation but most vocal of the ten-member association is Malaysia. Most strikingly, Malaysia dissociated from the official statement released by ASEAN because it did not explicitly mention the term “Rohingya.” More recently, a non-partisan petition by Malaysian parliamentarians to request for the national oil and gas company Petroliam Nasional Berhad (PETRONAS) to withdraw from Myanmar has received wide support from politicians and academics alike.

There seems to be no light at the end of this humanitarian crisis. But each day there is insufficient action, more and more people lose homes and possibly their lives and the scars to our collective humanity continue to deepen.

Recommended stories: