In 2017, industrial ecologist, Roland Geyer, led a study on the ‘Production, use and fate of all plastics ever made’ and estimated that there are more than 8.3 billion metric tons (Mt) of plastics that have been produced since the 1950s. The study also found that in 2015, only nine percent of plastics have been recycled, 12 percent incinerated and 79 percent accumulated in landfills or the ocean. If this trend continues, it is expected that roughly 12,000 Mt of plastic waste will be in landfills or the natural environment by 2050.

It is undeniable that plastic waste contributes to the earth’s ecological devastation and issues in human health.

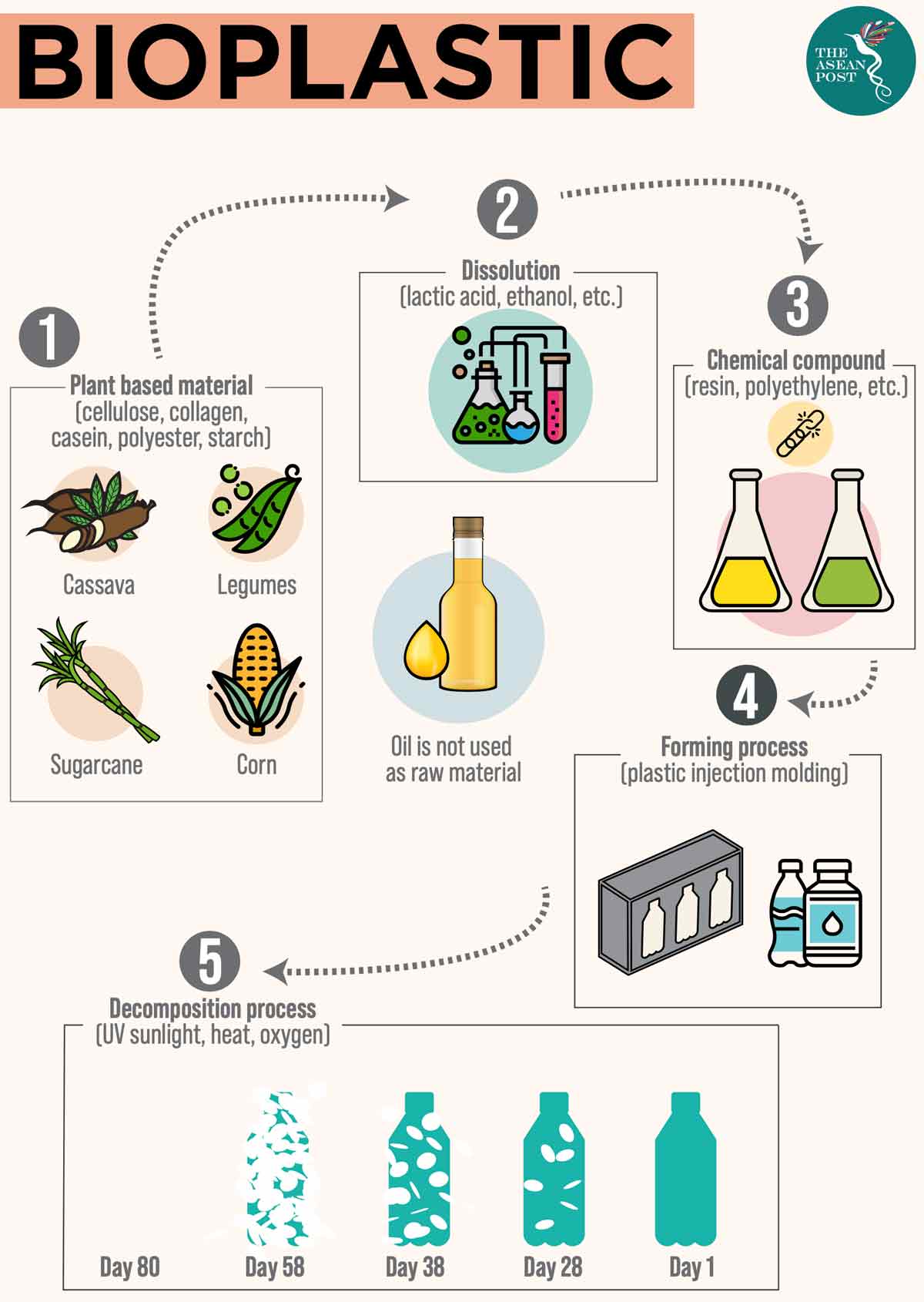

The global plastic industry today is considering alternatives, especially the use of more sustainable materials like bioplastic which is a plant-based alternative made from renewable materials like starch from corn, potato, soy protein, cellulose and lactic acid. The use of plants makes bioplastic a more Earth-friendly product.

Perceived to be environmentally friendly and non-toxic, bioplastic is now extensively used to make shopping bags, packaging and cutlery.

According to market data compiled by the Nova Institute, a market research firm, the global bioplastic production capacity is set to increase from 2.11 million Mt in 2018 to about 2.62 million Mt in 2023. Currently, bioplastic represents less than one percent of the total global market, but it is expected to grow at least 20-30 percent in the coming years. The firm claims that the global bioplastic market recorded a market valuation of more than US$4 billion in 2017 and is expected to reach a value of US$14.9 billion by 2023.

The same research also found that Asia is a major production hub for bioplastic, with an expected growth of 45 percent in global production capacity by 2021.

Traditional manufacturing processes of plastic use non-renewable resources, whereas bioplastic does not depend on fossil fuels for its production. And the energy required is half of the energy required for non-biodegradable plastics. Bioplastic also breaks down faster, with a minimum amount of harmful carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions.

Regional efforts

Thailand’s thriving agriculture industry has led the country to pursue a bio-based solution to its plastic waste problem. Thailand’s Eastern Economic Corridor (EEC) is turning to bioplastics derived from local plant products like cassava starch and sugarcane to manufacture new options that decompose completely after a few weeks.

Indonesia is also producing biodegradable plastic from cassava roots. Bali-based Avani Eco, a company that manufactures sustainable products, has created a plastic alternative, made from cassava starch which contains zero petroleum-based components. The strength of Avani Eco’s bioplastic is comparable to that of normal plastic and can dissolve in water without causing any harm to the environment. Inventor and founder, Kevin Kumala says that the plastic is so safe, that even humans can swallow it. Bioplastics made from cassava starch are biodegradable and compostable, breaking down over a period of months on land or at sea.

Ganjar Pranowo, Governor of Central Java in Indonesia, looks forward to the development of bioplastics. “We have already produced bioplastic, but it is not yet popular. I will issue a policy to push [the wider use of] bioplastics,” he said. His administration is looking to gradually replace plastic packaging with bioplastics. The Indonesian government has also pledged US$1 billion to reduce marine waste by 70 percent by 2025. It is a significant move as Indonesia’s plastic waste accounts for 10 percent of global marine plastic pollution. The country is the second-largest plastic polluter in the world after China – and produces 3.2 million tonnes of mismanaged plastic waste each year.

Seaweed is another alternative material for bioplastic production. Indonesian start-up, Evoware, has invented containers made from farmed seaweed. Seaweed is claimed to be the best option as it can grow without fertilisers and does not take up space on land as it grows offshore. Though more research is needed, there is potential in seaweed to be developed as an eco-friendly plastic option.

Unfortunately, the benefits of bioplastic can be exploited by unscrupulous plastic manufacturers passing off fake bio-based plastic bags as 100 percent biodegradable. In Malaysia, confusion still reigns among business owners who “wanted to abide by the ruling [of single-use plastic ban] but were wrongly influenced by vendors who sold photo-degradable, oxo-degradable, or even substandard biodegradable plastic bags,” explained Dr Noor Akma Shabuddin, Kuala Lumpur City Hall (DBKL) Health and Environment Department director. “These plastics are more damaging as they do not completely degrade but fragment over time into smaller plastic and microplastic particles.”

There are also environmental issues associated with the cultivation of plants for bioplastic. Among them are pollution from fertilisers and pesticides and having land diverted from food production, especially when agriculture land is already limited. For a plant-based plastic alternative to have a low environmental impact, crops must be grown sustainably. Without a proper disposing method, bioplastic will contribute to even more rubbish in waste streams.

Nonetheless, the changing trends across the globe indicate that the future of the bioplastic market in Southeast Asia is bright and promising. For the market to further expand, businesses, policymakers and investors need to come together and make clear commitments to collaborate towards a circular economy of bioplastic.

Related articles: