In a speech at the World Economic Forum in Davos earlier this year, billionaire business magnate, George Soros heavily criticised platform giants – Google and Facebook – who considered themselves “masters of the universe.” They had, in his words, become “monolithic powers” who may one day have near totalitarian control and Soros called for their global dominance and monopoly to be stemmed.

“Davos is a good place to announce that their days are numbered,” he concluded dramatically.

Regardless of one’s opinion of Soros, his remarks are not far from the truth.

It is no surprise that giants of the information technology (IT) world, Facebook and Google have had an increasing influence in our lives. The numbers are all the proof one needs.

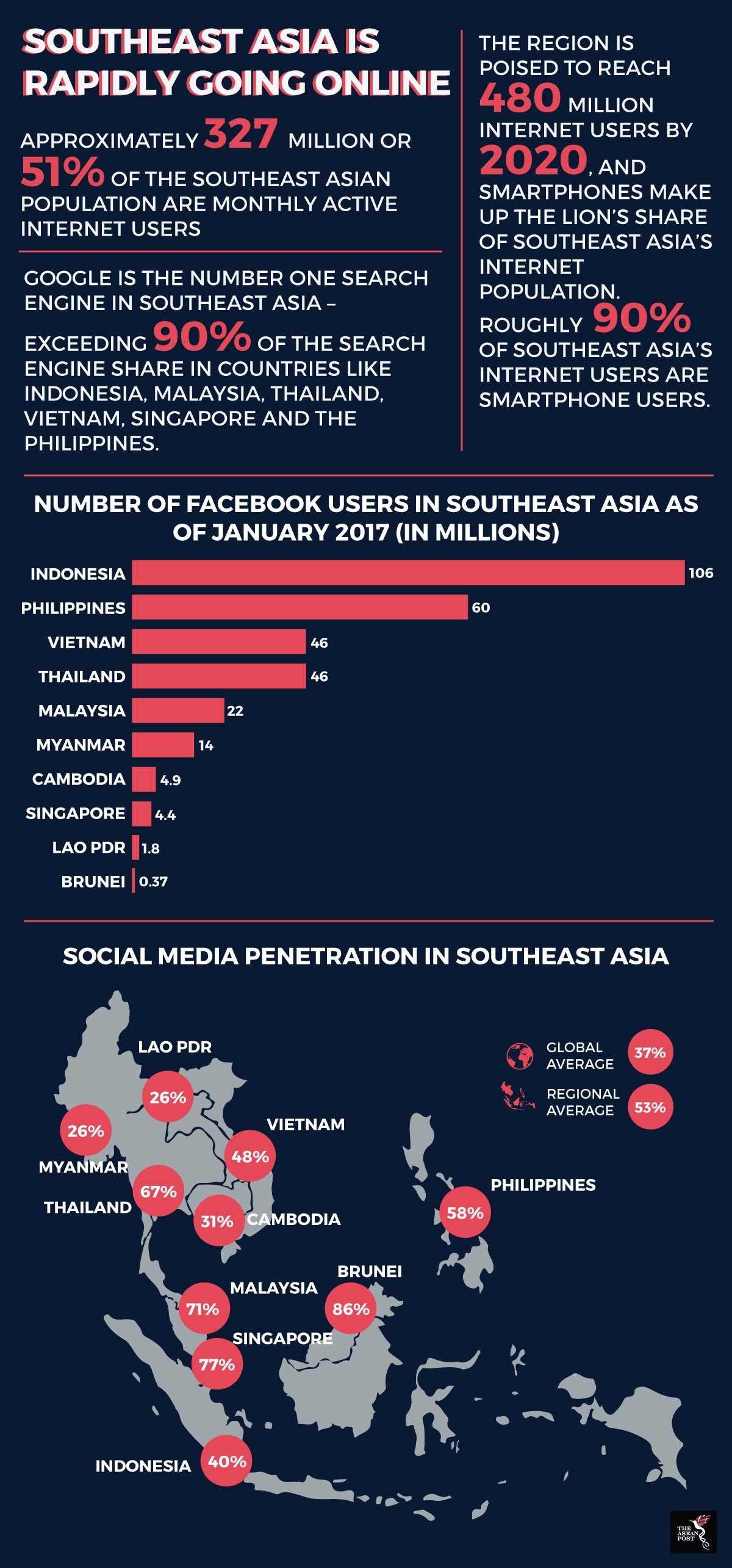

Southeast Asia’s current internet penetration is 51 percent or 330 million of the region’s population which is expected to hit 480 million by 2020. Over 90 percent of internet users get online via their smartphones and the lion share of the search engine market is captured by Google.

Exceedingly, social media is becoming an integral part of life. According to a 2018 report by We Are Social, social media penetration in member states of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) stands at 53 percent – 16 percent higher than the global average of 37 percent. Sites like Facebook and Instagram are not only used to communicate and to keep in touch but are also increasingly used for e-commerce, especially by small and micro businesses.

Big brother vs bigger brother

The currency that fuels Google’s and Facebook’s continued dominance is down to one thing – information. They have amassed swathes of information on their users who voluntarily share these details as they engage in their daily internet activities.

However, the likes of Google and Facebook have met their match in Southeast Asia, in the form of government controls. Call a spade a spade – governments in this region are not full democracies, preferring instead to hold on to a certain degree of authoritarian values. Even the region’s best overall performer, Singapore has been accused of stifling its opposition for many decades now.

However, what IT giants are more concerned with are their purse strings. They are ever willing to contort to the whims of Southeast Asia’s governments or risk being banned and lose a precious slice of the wealth in this growing market.

In Vietnam, Facebook has prioritised government requests to take down postings that are deemed to paint the state and its officials in a bad light. Facebook has also complied to similar requests in Thailand to take down posts demeaning the royal Thai family. Malaysia is in the midst of enacting laws to combat fake news purveyed via social media. The “fake news” label is one which is increasingly used freely by leaders in the region to dismiss any information that doesn’t fit their state’s narrative. Indonesia and the Philippines’ governments have in the recent past, flirted with the idea of imposing a ban on Facebook.

What this points to is state ambition to control information on the one hand and on the other, internet tech companies looking to stay on a government’s good side to remain in that particular country’s market. Consider information as a commodity and at the gates are corporations like Facebook and Google, looking to extract and utilise it to their benefit while being nice to the government in question to ensure access.

In the past, social media played a vital role in disseminating information which was otherwise inaccessible to the public. It helped in opposition uprisings and democratic movements from Malaysia, to Indonesia and Vietnam – just to name a few.

However, since the advent of troll farms and actual distribution of fake news and misinformation via social media sites – as evidenced by the 2016 US Presidential elections – media giants have had their images tainted. Call it an algorithm error or pure greed by these media companies which benefitted financially from advertisement revenue by fake news providers, governments now have a trump card that they can use over them.

The message is clear to social media providers; either work with the governments in question or face being ostracised.