Among all the 10-member states of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), Myanmar lags behind in terms of electricity connectivity to the national grid. Only 35 percent of the population is connected to the national grid, according to a report published by Baker & McKenzie in October, 2017. However, demand for power is rising as the engines of growth in Myanmar slowly kick into high gear and rural Myanmar becomes electrified.

Projections by the World Bank indicate that annual economic growth is slated to breach the 7 percent mark this year. Relatedly, the Japan International Co-operation Agency (JICA) – Myanmar’s largest source of official development assistance (ODA) – estimates that demand for electricity is to see a fivefold hike to 15 gigawatts (GW) by 2030.

So where is Myanmar going to source the additional energy to power the state from?

One solution is hydropower.

Hydropower potential in Myanmar

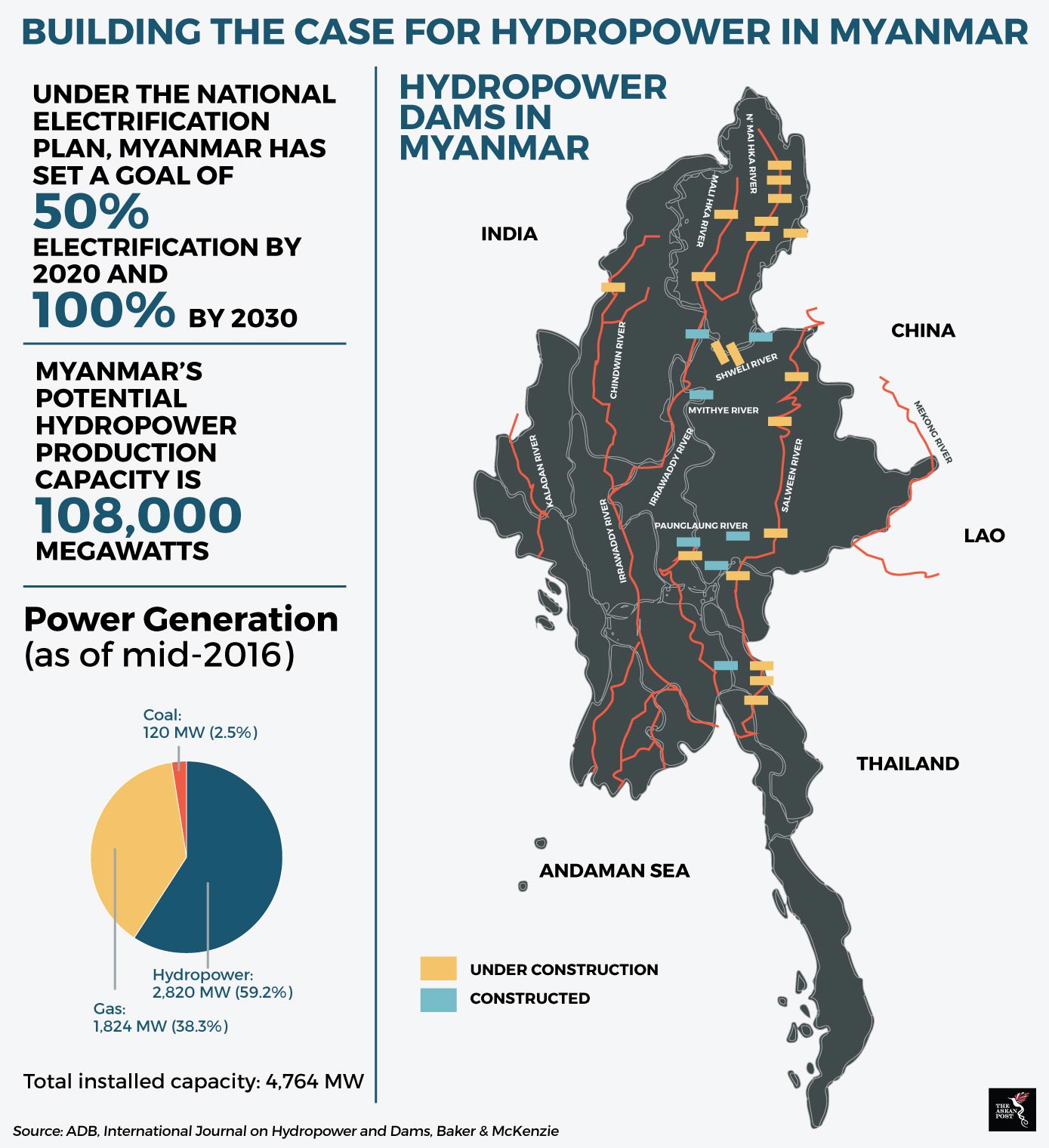

According to the Masterplan on ASEAN Connectivity 2025, Myanmar’s potential hydropower capacity is 108 GW. Already, hydropower is the country’s main source of energy for electricity generation representing 59.2 percent or 2,820 megawatt (MW) of the power generation mix.

This means that only 2.6 percent of the nation’s hydropower potential has been fulfilled. Given that Myanmar is bent on achieving 100 percent electrification rates by 2030, hydropower will play a crucial role in making that ambition a reality. If the plan materialises, installed hydropower capacity will more than triple to 9,000 MW by 2030.

The government of Myanmar has already embarked on upwards of 40 hydroelectric dam projects in major rivers in the country. Five of these projects are mega-dams (over 1,000 MW). The International Hydropower Association states that the largest hydropower potential in the country can be found in the Kayin, Shan, and Kayah states, where the Salween River flows.

Although Myanmar’s new civilian led government is relatively inexperienced in dealing with businesses related to the power sector as was highlighted in the report by Baker & McKenzie, evidence of increased international engagement is nevertheless a step in the right direction. Myanmar has engaged with several Chinese, European, North American, Thai, Indian and Japanese firms to deliver on hydropower projects around the nation.

Japan based Toshiba – via its Chinese subsidiary – clinched the contract for a 308 MW Upper Yeywa hydropower facility which is expected to be operationalised in 2018. China’s Hanergy Group in collaboration with Asia World was approved to develop a 1,400 MW Upper Thanlwin project which would also provide electricity to parts of south western China. Besides that, the Shweli 3 project is slated to be constructed by a French state-owned company Électricité de France SA (EDF) whereas the Middle Yeywa and Bawgata projects are to be built by Norwegian state-owned SN Power.

The case of Tanintharyi

As more and more hydropower projects are planned, the looming question of environmental impact remains. Hydroelectric dams have been known to negatively impact the biodiversity and ecology of the area due to the damming of water. It has also been reported that such dams destroy natural habitats, obstruct fish migration paths and tamper with the salinity of water. Inadvertently, these implications have affected the livelihood of fishermen and farmers dependent on the rivers as their main source of income.

Such is the dilemma faced in the development of a planned hydropower project in the Tanintharyi coastal basin.

The project is important to ensure that citizens in the surrounding rural areas gain access to the national grid which would significantly reduce their electricity costs – having being dependent on expensive diesel-powered generators for power. However, the project is not without its critics.

A report released last year by the World Bank indicated that there has been a lack of transparency and coordination by the developers and the government which ignited the furore of the local community. Besides that, the environmental impact assessments (EIA) prior to the project were weak and didn’t include negative impacts of the project.

“Often, no compensation is paid to local people affected by the project. There is a need to include local knowledge in EIAs and before the project is planned,” the report stated.

All this points to a necessary balance required to ensure sustainable development of such projects. Hydropower will undoubtedly raise the eyebrows of most environmentalists. But herein is a chance for Myanmar to prove its critics wrong. It needs power for its people and to grow the economy; doing so in a sustainable manner will definitely raise its profile in the international arena.

Recommended stories: