The concept of a technology park first emerged in the 1950s in the United States, when such parks were first built to accommodate high technology industry occurring at the time. The term is still used to denote dedicated areas developed specifically to encourage the localisation of high technology firms in areas such as fintech software development, artificial intelligence and the internet of things, among other technologies.

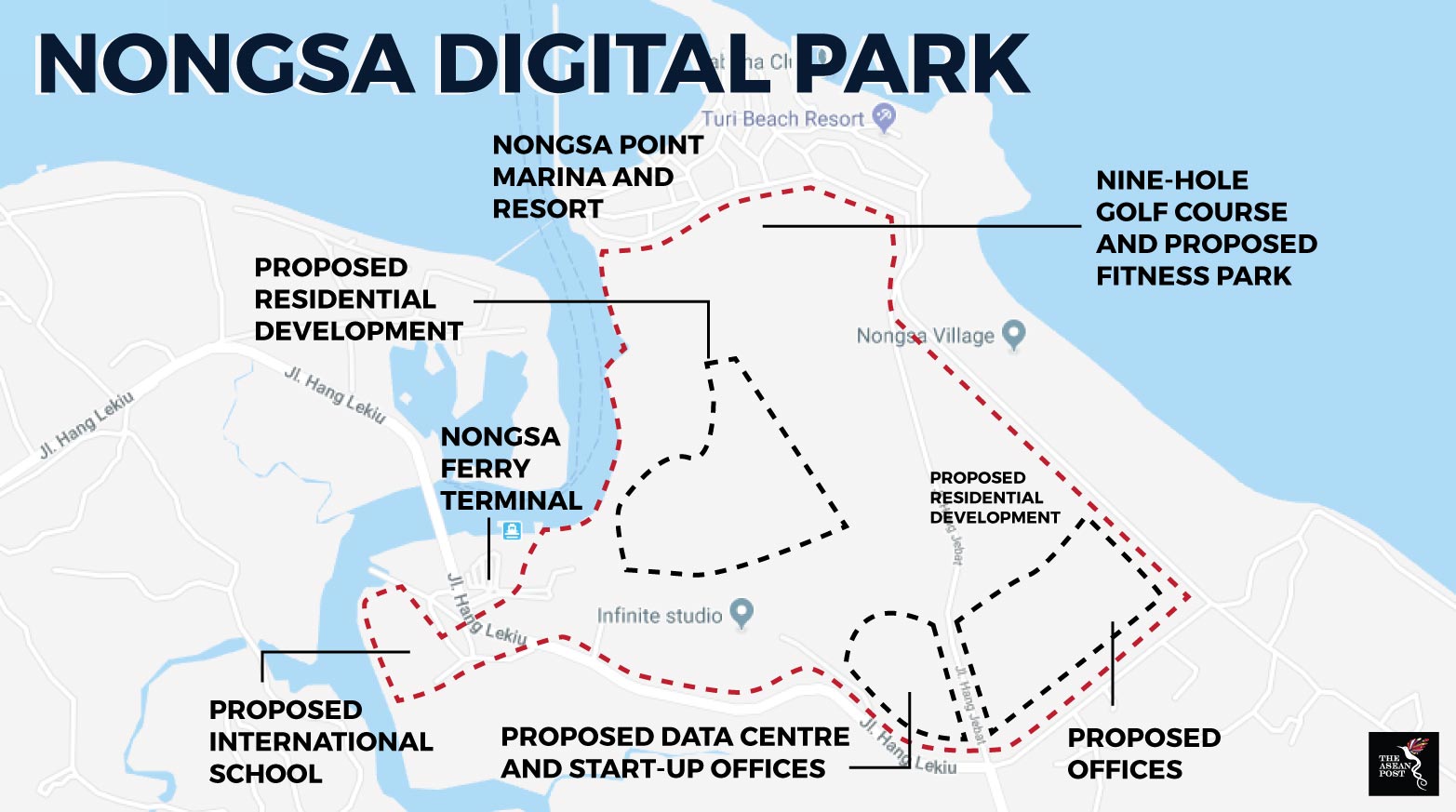

Indonesia is the latest Southeast Asian country to open a tech park. Located in Batam, the Nongsa Digital Park is being marketed as a digital bridge connecting Indonesia and Singapore’s digital economies.

“The Nongsa Digital Park is a beginning, a pilot project of our further efforts to achieve Indonesia’s digital economy potential,” said Retno Marsudi, Indonesia’s foreign minister at the launch of the park.

Thus far, Southeast Asian countries have developed tech parks to draw foreign investments to help them develop local technology, which will in turn spur long-term economic digitalisation. This is largely through start-up incubation, which helps attract the necessary tech talent in a given field too. The Nongsa Digital Park, for example, is expected to draw investments worth US$500 million and create 1,000 new digital start-ups worth US$10 billion by 2020.

Whether Batam will attract the investments it is targeting will also depend on whether there are enough tech start-ups interested in setting up hubs there.

“It has to be compelling enough for people to want to go there instead of Jakarta, where there is also talent and many start-ups,” industry observer Alfred Siew was quoted as saying.

Other Southeast Asian nations are also designing tech parks to suit their own economic objectives. Thailand’s new ‘Digital Park Thailand’, to be developed under a five-year roadmap (2018-2022), aims to attract digital innovators and disruptors in line with its Thailand 4.0 economic model. Although the project masterplan has yet to be revealed to the public, it is anticipated to be developed in three phases, with the park itself divided into three zones, namely an innovation space, a university 4.0 and a living space.

Vietnam’s tech parks meanwhile have already made headway. Last year, Vietnam’s three hi-tech parks, namely the Ho Chi Minh City Hi-Tech park, Hoa Lac Hi-Tech park and Da Nang Hi-Tech park attracted investment projects worth a combined total of US$10 billion. Samsung and Intel both have manufacturing facilities in Ho Chi Minh City Hi-Tech park, with Samsung alone creating around 15,000 jobs from the development of televisions and other consumer products there.

In Singapore, the focus is currently more on developing what it alternatively terms as ‘digital districts’, or ‘enterprise districts’, which are ring-fenced districts allocated to a specific mix of industrial activities, supported by a wider ecosystem of amenities and research facilities.

The new pilot Punggol Digital District will open progressively from 2023 onwards and is targeted to create 28,000 new jobs in data analytics, artificial intelligence and the internet of things, among other areas. The District will also house a Singapore Institute of Technology (SIT) university campus, with the potential of start-ups being set up within the campus itself, creating the possibility of more partnerships being formed between businesses and academia.

“Our plan is to capitalise on future trends and the key assets in each area to develop highly integrated and inclusive spaces to live, work, play and learn. Each district will have a unique role in contributing to Singapore’s growth in the future economy and be defined by a distinctive identity and environment. Punggol Digital District will anchor the north-east region and be the key in driving our competitiveness in this age of the digital economy,” said Teo Chee Hean, Singapore’s deputy prime minister in a press statement.

The Punggol Digital District will essentially incorporate Smart Nation initiatives, by availing cashless hawker centres and a hub parking system, for example. Energy-efficient systems such as an experimental urban micro-grid integrating gas, electricity and thermal energy into a single smart energy network will also be tested in that setting.

Singapore needs all the tech talent and resources it can get to fulfil its Smart Nation goals and sees extending regional partner collaborations as one way to get at this.

“Singapore’s ICT sector is thriving but future growth also depends on access to larger markets, technology and the availability of talent,” commented Singapore’s foreign minister, Dr Vivian Balakrishnan.

Although tech parks are just one of many roads leading up to the realisation of a digitalised economy, they are important spearheads in this direction, laying the necessary groundwork for deeper partnerships and innovation to take place. The devil, however, as they say, is in the details. Whereas the right mix could make tech parks one of the most attractive ‘playgrounds’ to work in, the opposite could also ring true. It is therefore important for governments to do the necessary research and planning to bring in the right partners before they roll out initiatives of this nature as there is too much at stake.