The recent approval of Thailand’s new Eastern Economic Corridor (EEC) bill is a step forward by Thailand's military government to rapidly industrialise the nation, but it should also consider the risks involved in doing so too quickly.

The EEC refers to the economic zone in Thailand that comprises of the three eastern provinces of Chachoengsao, Chonburi and Rayong, spanning a total distance of 13,285 square kilometres.

The new EEC developments will build upon the Eastern Seaboard Development Program, a similar project launched in the EEC region in 1982 which helped to transform Thailand’s automotive, petrochemical and electronics industries into the high-growth areas they are today. The Eastern Seaboard Development Program increased national exports by 12% over the last 20 years, according to data compiled by Thailand’s Ministry of Industry in 2017.

“The new EEC is expected to bring about a second wave of development for the region, thereby taking Thai industries to the next level,” explained Somkid Jatusripitak, Thai Deputy Prime Minister to the Nikkei Asian Review in February, 2018.

The newly approved EEC Act will provide tax incentives such as personal income tax reductions of up to 15% for local and foreign investors, and 0% corporate tax for up to 15 years. Additional incentives also include 99-year land leases and five-year work permit visa approvals for foreign workers, according to Kanit Sangsubhan, secretary general of the Eastern Economic Corridor office.

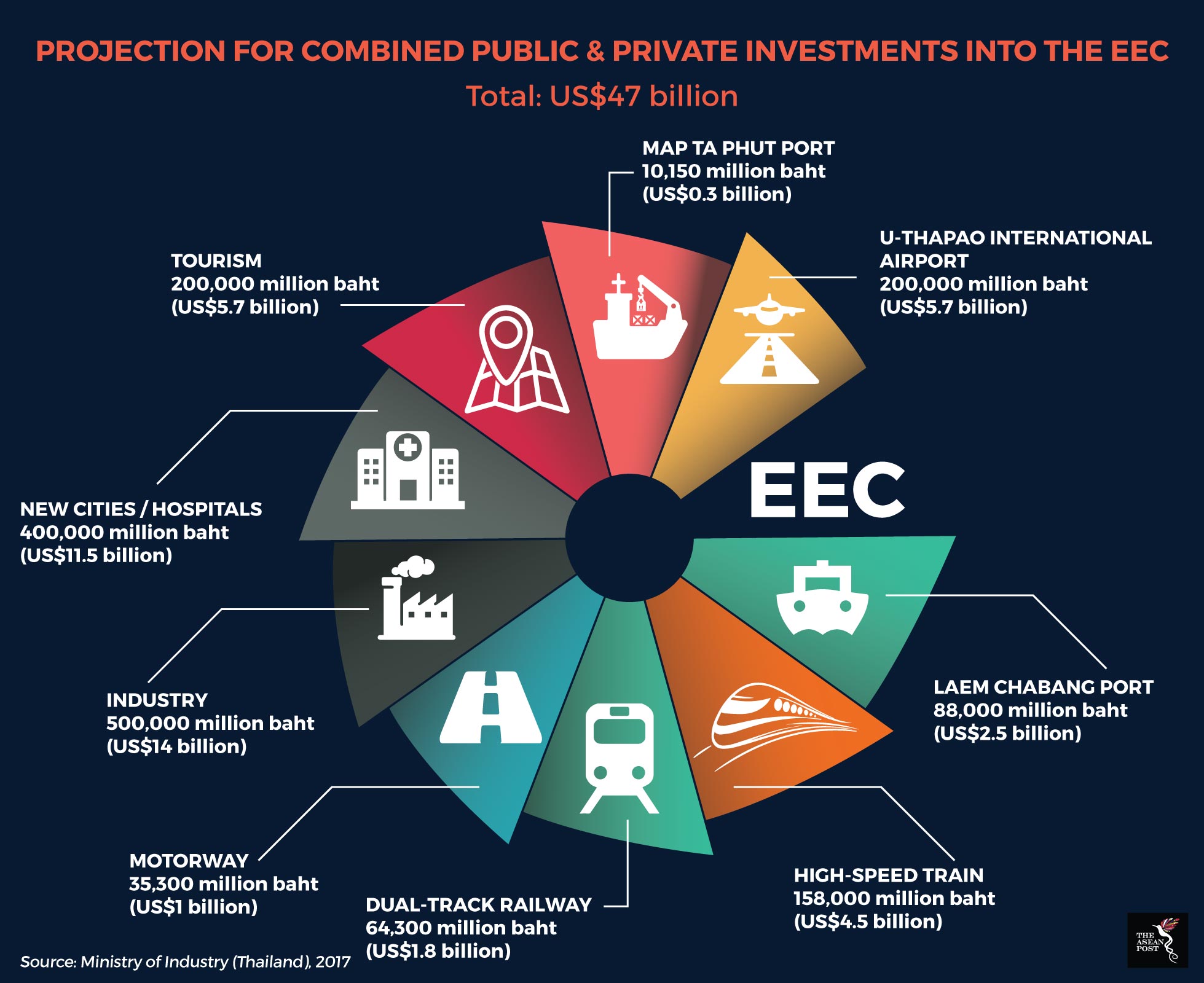

These are necessary in order to achieve Thailand’s US$22.5 billion foreign investment target in 2018, according to Xinhua News Agency. Thailand is expecting to draw EEC funding from a mixture of state funding, foreign direct investment and public-private partnerships, according to reporting by the Bangkok Post.

Most of this foreign investment is expected to come from China and Japan, but the Thai Ministry of Industry is also planning to hold roadshows in the United States and Europe to attract investments for the EEC.

“The stability of these economies will help to support Thailand’s targeted industries over the long run,” said Uttama Savayana, Thailand’s Industry Minister.

The 10 industries targeted for development under the new EEC incorporate Thailand's 4.0 Initiative, and include biotechnology, agricultural technology, digital technology, automotive, medical & wellness tourism, food, logistics and aviation, biofuels and biochemicals and medical services and smart electronics.

It was reported by Bloomberg in September 2017 that the Thai government has been looking to implement the new EEC law as soon as possible before the Thai elections, in order to assure investors of the sustainability of EEC projects post-elections. Projects are currently being implemented under the Thai prime minister’s absolute powers conferred by Article 44 of the post-coup Thai constitution, but these may be overhauled completely after the elections, leaving investors in a possible state of limbo.

The election date has been postponed several times to date. According to reporting by The Bangkok Post in February 2018, the election date is likely to be pushed back again to February 2019 at the earliest.

In the meantime, with the approval of the new EEC law, projects in the pipeline can go ahead. Projects will be developed in three stages, according to reporting by The Bangkok Post in February 2018. The first stage, to be carried out in 2018 will focus on attracting foreign and local investors to the EEC, the second (2019-2022) will develop transportation, and the final (2022 onwards) is focussed on building transport links with neighbouring countries.

“The introduction of the EEC law will accelerate development of five high-priority projects in particular,” said Kanit to the Nikkei Asian Review in February 2018.

The five projects in question are the expansion of Laem Chabang and Ma Thaput deep seaports, the development of U-Thapao commercial airport, the development of a high-speed rail network connecting Thailand’s U-Thapao airport to Suvarnabhumi Airport and Don Mueang Airport, and progress on the joint venture between Thai Airways and Airbus to construct a maintenance facility close to U-Thapao airport.

Although these projects may be successfully implemented, it remains to be seen whether they will benefit citizens as much as the Thai military government is hoping for.

“If the local people are lucky enough not to be driven from their land for special economic zone development, they will find themselves alienated in their own homeland as all the regulations and resources will only provide benefits for foreign investors,” noted Somnuck Jongmeewasin, a lecturer at Silpakorn University.

Other concerns include the possibility that the new EEC will simply be an avenue for foreign direct investors to funnel profits out of Thailand, given the large tax breaks, and the possibility that new jobs creation will mostly only benefit foreign workers, and not locals. Although clearly in a rush to implement EEC as soon as possible, it would perhaps be wise for Thailand’s military government to consider these risks carefully for the long-term future of the nation, and not just to cement their place in history.

Recommended stories: