The wealth of nations is often measured by its physical, natural and institutional resources. Seldom, if ever, are their human capital considered as economic resources. When the International Monetary Fund (IMF) or World Bank offer financial aid, they usually impose conditions to limit public spending on health and education.

That approach may be revised in future as the World Bank has recognised the value of human capital to a nation’s economic future. It recently launched its inaugural Human Capital Index (HCI) at its annual meeting with the IMF in Bali.

It is hoped that the new ranking system will encourage competition among countries to do more and to improve. World Bank Group president Jim Yong Kim said even the poorest countries could implement measures to improve life chances. Providing additional funds to developing countries is insufficient and offering better ways of teaching, parenting and providing healthcare is equally important, he said.

“For the poorest people, human capital is often the only capital they have,” he said. “It is a key driver of sustainable, inclusive economic growth but investing in health and education has not gotten the attention it deserves.”

The World Bank only began to realise the importance of human capital last year, revealed Kristalina Georgieva, CEO of the World Bank. “It was a shock because we discovered that two-thirds of the planet’s wealth is people. A richer country would have a higher share of human capital in its wealth.”

By improving human capital in the form of skills, health, knowledge and resilience, a population can be more productive, flexible and innovative. Investments in human capital have become more important as the nature of work has evolved, said the bank.

Three key components

The current iteration of the HCI is based on three components: mortality rates up to age five and survival rate to age 60; the healthy growth among children under age five; and the quality of education.

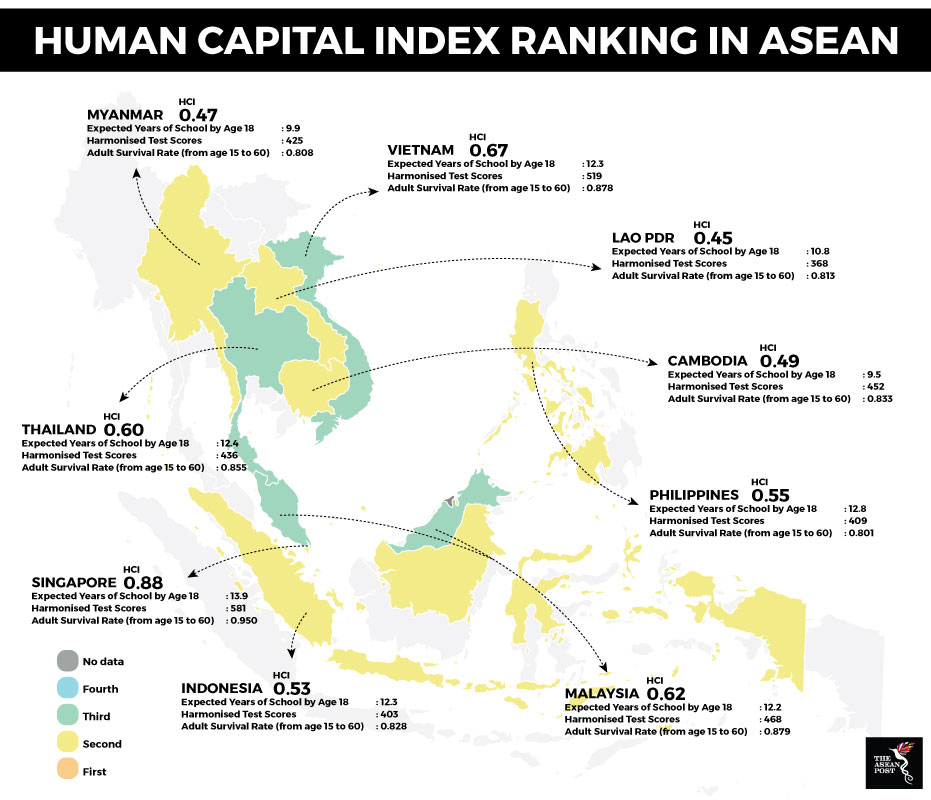

After suffering the ignominy of being in the bottom 10 of Oxfam’s Commitment to Reducing Inequality Index the previous week over its low tax rates, Singapore should be happy to be ranked top on the HCI. ASEAN countries generally rank quite high among the 157 countries measured, while African nations occupy the bottom 21 positions.

An indignant India, ranked 115th below neighbours Nepal, Sri Lanka, Myanmar and Bangladesh, rejected the HCI, claiming it ignored the nation’s human capital development programmes.

Source: World Bank

Source: World Bank

The HCI indicates the productivity of a child when he/she grows up compared to his/her potential productivity if he/she received a complete education and enjoyed full health. Singapore’s HCI of 0.88 means a child will be 88 percent productive.

Vietnam takes second place among ASEAN nations, indicating significant efforts to improve healthcare and education despite being in the lower-middle income category. Malaysia – an upper-middle income nation – came in third.

The index also indicated ASEAN countries have very low infant mortality rates: more than 93 percent of children born survive to age five.

The World Bank measures education by the expected number of years a child spends in school. In the region, Singapore’s children top the list. By the age of 18, they would have spent 13.9 years in pre-school, primary and secondary schools.

Children in the Philippines, Thailand, Indonesia, Vietnam and Malaysia enjoy more than 12 years of schooling. Myanmar and Cambodia children have less than 10 years of schooling, indicating limited education facilities.

To factor in the quality of education and what children actually learn in school, the World Bank incorporated learning-adjusted years of school and harmonised test scores in its index.

Singapore’s learning-adjusted years is an impressive 13 years. Its children get 13 years’ worth of education within the 13.9 years spent in school. Coming in second in ASEAN is Vietnam, whose children get 10 years of education in the 12.3 years of schooling. Third is Cambodia with 6.9 years of education in 9.5 years of schooling.

The World Bank worked on harmonising test scores from major international student testing programs to create a single metric for learning outcomes: 300 points represent minimum attainment while a score of 625 indicates advanced attainment.

Singapore also scored top marks here with 581, beating Japan and South Korea in the world’s top three. Down in 27th place is Vietnam, followed by Malaysia in 65th placing.

The quality of healthcare is calculated by the survival rates of 15-year-olds living until the age of 60. This represents the range of fatal and non-fatal health outcomes that a child born today would experience as an adult under current conditions.

Macau, Iceland and Switzerland top this list. Singapore sits at seventh place with 95 percent survival but still leads the rest of ASEAN. Within the ASEAN grouping, the Philippines ranks lowest with 80 percent survival rate.

The World Bank concluded that the HCI for Cambodia, the Philippines, Singapore and Vietnam is higher than what would be predicted for its income level. Thailand’s HCI is on par with predictions for its income levels. However, the HCI for Indonesia, Lao PDR, Malaysia and Myanmar is lower than predicted for their income levels, indicating there is plenty more room for improvement.

Related articles:

A race to close the inequality gap

Making women in leadership a norm

Vietnam, the land of the 'Ascending Dragon'