Global waste is expected to grow to 3.40 billion tonnes by 2050, more than double the population growth over the same period. According to a 2018 World Bank report, ‘What a Waste 2.0’ on solid waste management, the East Asia and Pacific region generates most of the world’s waste, at 23 percent.

Landfills have been the cheapest method of disposal but the rapid growth of waste is making it harder to manage. As our garbage woes worsen, the region is looking at the option of managing massive waste by turning it into electricity. Although there are many methods of turning waste into power, incineration is the cheapest and best-known waste-to-energy (WtE) technology, eliminating the physical burden of waste while producing much-needed energy.

Japan recently expressed its intention to become Southeast Asia’s trash manager, setting aside US$18.6 million in its fiscal 2019 budget for developing proposals and bidding on waste management deals in Southeast Asia.

Japan currently has 380 WtE plants nationwide, and is offering service packages that include waste disposal systems and expertise in different aspects of trash management, like collection and separation. Japan will also propose specialised plans to tackle trash pileups in Philippine cities and polluted groundwater in Vietnam and Indonesia.

Across ASEAN

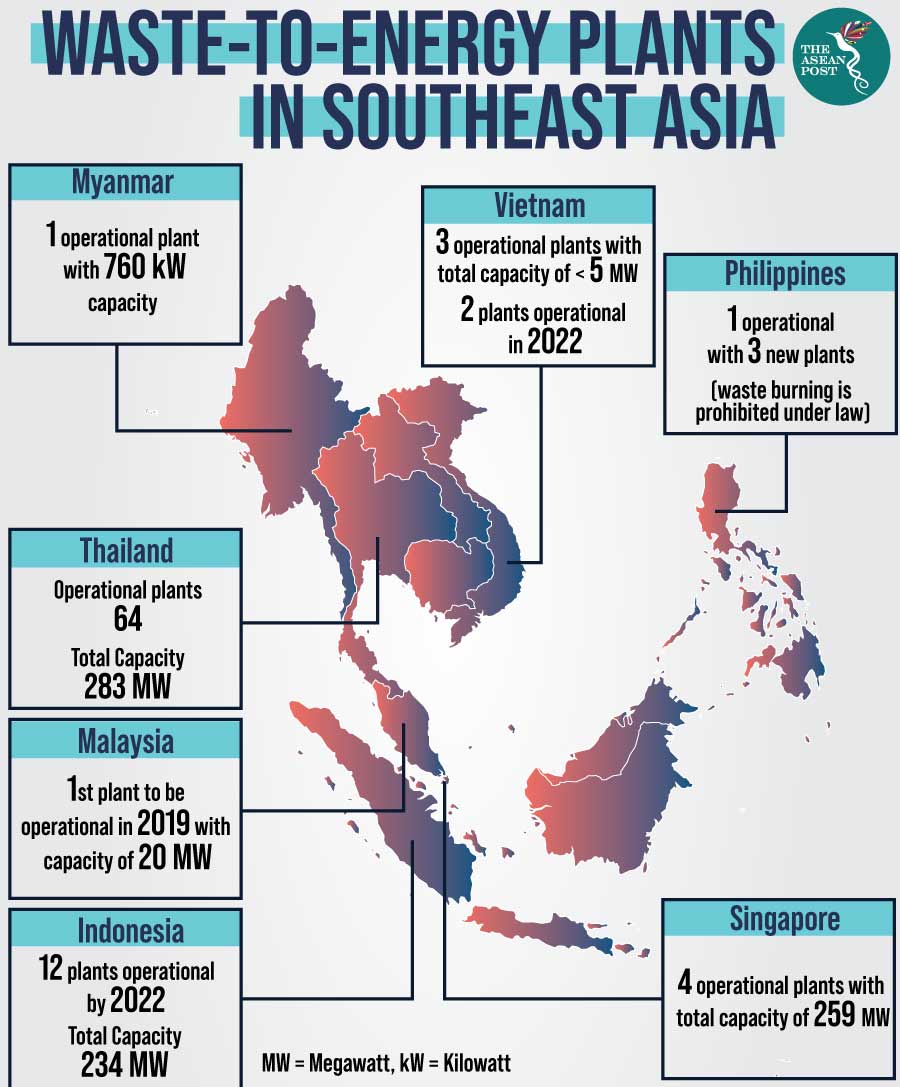

Vietnam produces an average of 70,000 tonnes of waste per day, and with WtE plants in place, it is estimated that it could produce around one billion kilowatts per hour (kWh) in 2020, and six billion kWh in 2050 – just from waste. Currently, WtE plants in Vietnam include the Nam Son, Hanoi facility and the Go Cat waste handling project in Ho Chi Minh City with a capacity of 2.4 megawatts (MW). In Soc Son, Hanoi, a Vietnam-Japan government-to-government project plant is producing 1.93 MW of electricity.

WtE projects in the Philippines include a US$48 million plant set to start construction in Davao City, a US$40.5 million project in the pipeline in Puerto Princesa City in Palawan and a facility already operational in Lapu-Lapu City in Cebu.

Malaysia’s first WtE plant is expected to be fully operational this year.

“In KPKT’s policy, we want every state to have at least one WtE incinerator within two years’ time, while we are phasing out landfill,” said Zuraida Kamaruddin, Housing and Local Government (KPKT) Minister.

In April 2018, Indonesia’s President Joko Widodo issued a regulation to set up eco-friendly plants to turn waste into electricity, as a means to tackle the country’s growing mountain of trash. Cabinet Secretary Pramono Anung said since then, cities including Jakarta, Surabaya, Bekasi and Solo have pledged to build such plants, which incinerate trash to drive turbines to create power. 12 WtE power plants are due to be operational by 2022 with a combined capacity of 234 MW of electricity using 16,000 tons of waste a day.

The Thai government has offered subsidies and tax incentives for various WtE plants, including incineration, gasification, fermentation and landfill gas capture. To further boost investments, the government there has increased the power purchase quota from 500 to 900 MW and allocated an additional budget of US$106.5 million to fund the waste management strategy.

Based on the Alternative Energy Development and Efficiency Department's database, there are currently 33 operational WtE plants in Thailand with an overall capacity of 283 MW. Building small, localised WtE plants was one of the core policies of the National Council for Peace and Order (NCPO). Out of the 33 plants, only two are generating more than 10 MW.

Protest over pollution

Sonthi Kotchawat, a leading environmental health expert, warned that careless development of WtE plants can cause a large environmental impact from hazardous pollution. Small energy plants are also causing more pollution, Sonthi said, pointing out that small plants do not share the same environmental protection standards as larger plants. The owners of these plants also do not have enough budget to invest in efficient but expensive pollution-trapping systems that is compulsory for larger plants.

Unsorted waste makes Thailand’s trash too full of organic and other non-flammable materials which reduce the ability of incineration plants to reach the high temperatures necessary to produce electricity and avoid toxic emissions and ash by-products. This has led some local communities and civil society groups to protest over pollution and health concerns.

Indonesia too faces similar challenges. Despite the government support for WtE projects, progress has lagged because of public backlash against incineration projects. In 2018, Indonesia’s Supreme Court ruled that incineration of waste was against the law because it produced hazardous pollutants.

Waste burning in the Philippines is also prohibited under the country’s Clean Air Act, but this has not stopped private companies from trying to construct waste incinerators that produce electricity.

Although incineration eliminates physical waste, moving beyond traditional incineration is important for sustainable and long-term operation of the plants. If well-managed, waste-to-energy can reduce the need for physical waste storage. Unmanaged waste will lead to further environmental impact. For more efficiency, a waste sorting system must be established so the region can use the best WtE technologies available today.

Related articles:

ASEAN leaders urged to ban trash imports